Paths to eurobonds

The defining feature of the European Monetary Union is that it was purposefully designed as a monetary union without a fiscal union. In this sense,

1. Introduction

The defining feature of the European Monetary Union is that it was purposefully designed as a monetary union without a fiscal union. In this sense, the political and intellectual consensus that gave birth to the euro was one in which this unusual form of economic and monetary union was deemed both politically and economically sustainable. Yet both the history of monetary unions (see Bordo et al (2011)) and the ongoing crisis seem to challenge this very assumption. Against the background of a broadening and intensification of the crisis, the need to durably stabilize financial markets is becoming ever more pressing and provides an additional urgent motivation to push for the introduction of commonly issued debt as a potent crisis resolution mechanism. As a result, the common issuance of debt in the euro area has been increasingly evoked, including most recently by the European Parliament and the President of the European Council both as a structural feature of the future monetary union as well as a potentially immediate response to the worsening of the financial crisis. It might become an even more important and urgent policy discussion as the current stabilization framework is showing its economic, financial and political limits (see Vallée and Blisjma, 2012 and the recent Karlsruhe Constitutional Court’s request on the ESM[2]).

2. Presentation of the proposals

The eurozone crisis has highlighted that economic and financial shocks may require arrangements of fiscal support for countries in crisis. But in order to reduce the need for mechanisms that serve as mutual insurance (the European Financial Stability Facility and the European Stability Mechanism), the monetary union needs to be complemented by fiscal transfers that help absorb asymmetric shocks, conduct aggregate countercyclical policy and finally promote income convergence motivated by economic and social reasons..

Common debt issuance, because it would help to strengthen financial safety nets and it would force to respond to longer-term questions surrounding fiscal risk sharing could be an important step in the redesign of the architecture of the European Monetary Union. It is in fact inextricably linked to the shape and form of the future fiscal union. But in order to achieve this, it needs to have the correct aim, in particular, it should seek to maximize the stabilizing effect on financial markets, achieve a degree of risk sharing while ensuring fiscal disciplines and appropriate incentives both for borrowers and creditors.

Common euro debt has been discussed for some time, although rarely starting from the perspective of its contribution to complete the architecture of the eurozone. Indeed, with the crisis, common debt became quickly seen as a possible crisis resolution tool. As early as May 2009, De Grauwe and Moesen (2009) suggested common debt to avoid diverging borrowing costs, with adverse consequences for debt sustainability and risks of propagation. Gros and Micossi (2009) followed with a proposal to leverage borrowing for joint European fiscal stimulus. A number of other proposals followed since.

There are currently five such proposals: Jacques Delpla and Jakob von Weizsäcker’s Blue-Red bond; the German Economic Experts’ European Debt Redemption Fund; the Euro-nomics group ESBies; Thomas Philippon and Christian Hellwig’s EuroBills; and those options summarized in the EC Green Paper for discussion of November 2011.[3] Yet despite their own merit, each of these proposals seem to address only a portion of the many objectives that common debt issuance is meant to serve. .

3. Objectives of commonly issued debt

The common issuance of debt could serve a number of different purposes and should be analyzed along different dimensions. These dimensions can be summarized in three sets of categories: (ii) fiscal discipline and fiscal risk sharing, (ii) financial and monetary stability, and (iii) monetary policy transmission mechanism and financial markets integration in the eurozone. There are evidently overlaps as well as conflicts between these objectives. A test for the proposals is how they help—by themselves or in combination with other initiatives—in balancing these objectives.

Figure 1: Objectives of Common debt issuance

4. Paths to Eurobonds

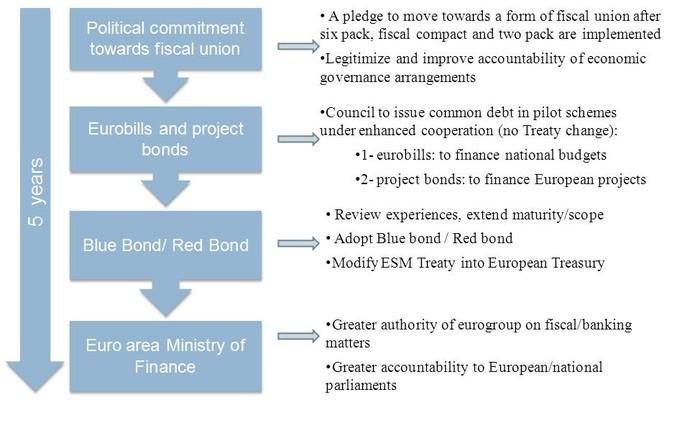

The various proposals’ success will depend on their ability to meet the objectives above while conforming to the political constraints. In this light, given the diversity of the objectives, these proposals should to some extent, be regarded as complements rather than substitutes. Indeed, some could be introduced jointly or in sequence in order to maximize their economic benefits and control for or mitigate their potential adverse consequences.. Among the many possible combinations and sequencing alternatives we review two, each leading to similar outcomes, including an equivalent fiscal union.

Path 1: A first path (Figure 1) builds on the recent governance changes and associated commitment to fiscal discipline and allows a permanent mechanism to emerge relatively quickly. It starts with the issuance of a limited amount of Eurobills (say, 10% per cent of Eurozone’s GDP) and longer-term project bonds backing specific projects (only a few billions euros each year). These two initiatives, being small, allow for learning and reversal should results be unsatisfactory or states weaken commitment to fiscal discipline. The exit possibility helps address the discipline objective while the reduced borrowing cost as well as the discretionary nature of the project bonds related expenditures allow for a degree of risk sharing and transfers. The other advantage is that Eurobills addresses sovereign-bank links right away, although on a small scale at first. This path allows moving towards a broad common debt issuance and introducing a form of fiscal union, yet it maintains a degree of control over the pace and dynamics of the transition and therefore could be seen as limiting the political costs.

However, the biggest risks with this path are twofold: the first one is of a political nature since, by design, it can be abandoned quickly (e.g., if a member state decides not to renew its guarantees) and might therefore lack credibility. Conversely, it can, if urgency calls for it, also easily be accelerated and expanded. In fact, urgency related to financial distress could dictate a more rapid expansion of Eurobills to cover an ever-larger share of mutually guaranteed debt issuance. One could therefore fear that eurobills would serve as a Trojan horse allowing vastly expanding guarantees and for this reason it should be complemented by strong mechanisms enforcing fiscal discipline. Yet the flexibility of the proposal allows adjusting the phase-in, and the timing can also be arranged to match the pace of democratic processes toward a broader revision of the EU Treaty formalizing more specifically the shape and form of a future fiscal union. As a consequence, the timetable proposed is purely indicative but underscores the fact that it could be quite rapid.

Figure 2: From Eurobills and project bonds to Eurobonds

Path 2: The second path (Figure 3) also builds on existing governance changes and aims to end with a blue bond-red bond type of solution while not using it as a starting point considering the risks associated with the issuance of red debt in the current context. The path uses as a starting point the Redemption Fund to mutualize a portion of the stock of debt in order to achieve lower debt-to-GDP ratios over the next 20 years. The financial stability contribution of the proposal is strong during the phase-in period where member states can issue debt under their allocation of redemption fund but it fades after they have exhausted their quota and each member state is then borrowing under its own name with a debt that is then potentially junior to it, or at least perceived to be. But in the short -term, the safer mutualized sovereign debt held on banks’ balance sheets under the Redemption pact immediate increases financial stability. This proposal addresses fiscal incentives via the long term binding commitment but doesn’t resort to price signals and therefore solely rests on the binding nature of the rules and the credibility of the adjustment commitment. Regarding fiscal risk-sharing, this dimension is limited in scope and more importantly in time. It also declines as the debt overhang reduces. But if successfully implemented, after 25 years, the debt-to-GDP ratio of participating states would converge to 60 percent.

With debt burdens more similar across member states, the Blue-Red bond proposal or other such permanent mutualization schemes could be introduced with less political tensions and concerns over moral hazard since the current worry that highly indebted countries would require permanent subsidies would have lessened. The joint and several guarantees would then present smaller ex-ante distributional consequences, while the market-disciplining role for marginal borrowing costs would presumably be more credible.

Yet this path is not without possible downsides, some arising from the limitations of each proposal individually, others from sequencing. In particular, the Redemption proposal assumes the implied consolidation paths to be tenable economically and politically. Since the sustainability and debt dynamics for key countries that would take part are currently being questioned, this raises some important credibility questions. It presumes no major shocks in any country over the period and countries to sustain fiscal adjustments rarely observed over such a long period in any advanced economy. In addition, the ability of still high-indebted countries to issue national, junior debts following the phase-in (during which their financing requirements are largely met) is unclear. If markets start to doubt the credibility of the adjustment paths, appetite for national as well as the common debt will drop, thereby threatening the Redemption pact’s feasibility. Finally, the transition from Redemption bonds to a form of Blue-Red bonds—and the accompanying strengthening of the fiscal union—may never happen. Indeed, the political will to introduce a permanent mechanism may be little if the Redemption fund fails (e.g., because member states deviated from their consolidation path) or if it succeeds and debt levels converge to a lower level and the urgency to pool debt recedes, thereby leaving the monetary union incomplete and exposed to future instability. It should be added that the common debt issued through the redemption fund will be biased towards debt from Italy and other high-debt countries, which may reduce its attractiveness in the eyes of investors.

Figure 3: From Redemption Fund to Eurobonds

Other combinations can be envisioned, such as introducing concurrently of the Redemption Fund and Eurobills (a report for the EU parliament by rapporteur Sylvie Goulard bears many parallels with this path). The Redemption fund would deal with the debt and adjustment of high-debt countries, while the Eurobills would provide some continuous market access at lower rates even after the phase-in period of the Redemption fund. This combination presents some benefits over the other two paths as deals concurrently with the flow and the stock issue, but comes at the cost of larger guarantees.

Overall, several combinations of initiatives can be envisioned that allow for a gradual introduction of common debt mechanisms while the necessary legislative and political changes for a tighter budgetary union are put in place. Legal and institutional dimensions related to the common issuance of euro debt are many. Legal questions relate to two constraints in particular: those pertaining to European Laws and Treaties; and those pertaining to the Laws and Constitutions of member states. There are also challenging institutional questions on the governance and the accountability framework for debt issuance from both EU and National/Constitutional perspectives. The main EU legal question is whether the introduction of jointly and severally guaranteed debt contravenes provisions of the European Treaty, in particular Article 125.[4] Many legal scholars[5], and the legal services of the Council, now interpret the Article 125 as compatible with joint and several guarantees as long as member states enter voluntarily into such agreements, however a Treaty change might still be required to lift ambiguity and bolster the democratic legitimacy of such an important change. The other important constraint rests with national laws and constitution in particular in Germany whose participation is essential in any common debt issuance scheme but more generally these legal challenges may occur in any of the participating countries. Three important rulings by the Court help to frame the Constitutional Court’s interpretation of these issues, one on the Lisbon Treaty in 2009, another on the EFSF in 2011 and finally the last one on the ESM in June 2012. These rulings limit the scope for intergovernmental guarantees to specific designs and limited amounts but more importantly they all stress the need for ongoing parliamentary involvement to support the accountability of these schemes and ensure their democratic legitimacy.

All in all, even if not strictly necessary, European and national laws changes are desirable as they would involve a process by which politicians, parliaments, and possibly voters are explicitly invited to opine on the new instrument in full knowledge of their economic and political consequences.

5. Conclusion

These proposals have clear benefits but should not be seen through the narrow prism of their effect on borrowing cost. Indeed, if the US history is to be of any guide, the pooling of the States’ debt following the war of independence by Hamilton in 1790 did indeed create the embryo of the United States’ fiscal federalism but short of a complete and deep seated political agreement on the full contours of the fiscal union including transfers eventually led to large scale State defaults in the 1830s and let in economic divergences that eventually culminated with the Civil War in 1861. In this sense, the common issuance of debt needs to be seen as one element, in the broader context of solidifying the economic and political architecture of the EMU.

But it is not clear whether mutualization can deal with potentially unsustainable debt dynamics anyhow. In this sense, the question of whether debt restructuring of some sort should be envisaged either at the end of a process of consolidation or at the beginning of a process of mutualization remains. More broadly, short of addressing all the aspects of a fiscal union (macro economic stabilization, burden sharing and income equalization) completely, common debt issuance can initiate a political process to this effect. But essential questions about the outcome of budgetary integration need addressing. In particular, it is key to understand whether this process should lead to a central authority with a power tax, spend and borrow or whether more intrusive controls on decentralized national budgets will suffice. Both options could probably be economically fairly equivalent but regardless of the path chosen, these alternatives require an open political discussion on the future EMU.

6. References

Balassa, Bela, Towards a Theory of Economic Integration, Kyklos, 1961

Bofinger, Peter et al., 2011, “A European Redemption Pact,” VOX.

Bordo, Michael, Agnieszka Markiewicz, Lars Jonung, “A fiscal union for the euro: Some lessons from history”, NBER Working Paper No. 17380, 2011

Brunnermeier, Markus et al., 2011, “European Safe Bonds (ESBies),” Working Paper.

Claessens, Stijn and Ashoka Mody, 2012, “Euro-bills and Euro-Safe Bonds,” Surveillance Meeting, February 7.

De Grauwe, Paul, and Wim Moesen, 2009, “Gains for All: A Proposal for a Common Euro Bond,” CEPS Commentary.

Delpla, Jacques, and Jakob von Weizsäcker, 2010, “The Blue Bond Proposal,” Bruegel Policy Brief.

European Commission, 2011, “Green Paper on the Feasibility of Introducing Stability Bonds,” Green Paper.

European Primary Dealers Association, 2008, “A Common European Government Bond,” Discussion Paper.

_________________, 2009, “Towards a Common European Bill,” Discussion Paper.

Favero, Carlo Ambrogio and Alessandro Missale, 2010, “EU Public Debt Management and Eurobonds,” European Parliament, Directorate General for Internal Policies, Note.

Gustavsson, Sverker, Monetary Union without fiscal union: a politically sustainable asymmetry?, Paper presented at the American ECSA Biennal Conference, June 1999, Pennsylvania, panel on EMU: Economic and Political Implications“

Hellwig, Christian, and Thomas Philippon, 2011, “Eurobills, not Eurobonds,” voxeu.org

Mayer, Heidfeld, 2012, “Verfassungs- und europarechtliche Aspekte der Einführung von Eurobonds,” Neue Juristiche Wochenschrift 422, February.

Tirole, Jean, The euro crisis: some reflexions on institutional reform, Banque de France Financial Stability Review, No. 16, April 2012

Von Hagen, Jurgen, Monetary Union and Fiscal Union: A perspective from fiscal federalism, in Policy Issues in the Operation of Currency Unions By Paul R. Masson, Mark P. Taylor, Cambridge University Press, 1993

[1] This policy contribution draws on a more expansive forthcoming IMF Working Paper by Stijn Claessens, Ashoka Mody and Shahin Vallée that provides a more analytical discussion on the introduction of commonly issued debt. The author is grateful to participants to the IMF-Bruegel conference held on April 4th in Brussels and participants to the EBRD-Bruegel conference held February 8th in London.

[2] The German Constitutional Court has requested a delay before it can opine on the constitutional legality of the ESM and the Fiscal Compact. http://www.spiegel.de/international/germany/german-high-court-requests-…

[3] These are not the only proposals, but they have attracted the most attention. The idea of project bonds has been widely discussed and often tied to the debate on common debt issuance but we have decided not to include it in our overview for we do not consider it to be real mechanism of debt mutualisation of a budgetary nature

[4] Article 125 TFEU: “The Union (…) and a Member State shall not be liable for or assume the commitments of central governments, regional, local or other public authorities, other bodies governed by public law, or public undertakings of another Member State, without prejudice to mutual financial guarantees for the joint execution of a specific project.”

[5] See Mayer (2012).