Blogs review: Inequality

What’s at stake: On Dec. 4, President Obama delivered an important speech on economic inequality and mobility, which he described as “the defining challenge of our time”. This has generated an extensive conversation in the blogosphere about whether reducing inequality or achieving full employment should be the top priority of policymakers. The discussion was also complemented with a preview of the new Piketty book on wealth inequality.

The lack of economic mobility as a fundamental threat to the American dream

Ezra Klein writes that it’s increasingly clear that the organizing economic concern of the American left is — or is becoming — income inequality. It's the issue that led protestors to occupy Zucotti Park. It's the anxiety that powered Bill DeBlasio's campaign for mayor of New York. On Dec. 4 President Obama called it -- and the decline in social mobility it heralds -- "the defining challenge of our time."

Bill Keller (HT Mark Thoma) writes that President Obama’s speech on Dec. 4, widely characterized as his inequality speech, was actually billed by the White House as a speech on economic mobility. The equality he urged us to strive for was not equality of wealth but equality of opportunity.

Barack Obama said that the combined trends of increased inequality and decreasing mobility pose a fundamental threat to the American Dream. The problem is that alongside increased inequality, we’ve seen diminished levels of upward mobility in recent years. The idea that so many children are born into poverty in the wealthiest nation on Earth is heartbreaking enough. But the idea that a child may never be able to escape that poverty […] offend all of us and it should compel us to action. […] A child born in the top 20 percent has about a 2-in-3 chance of staying at or near the top. A child born into the bottom 20 percent has a less than 1-in-20 shot at making it to the top. The opportunity gap in America is now as much about class as it is about race, and that gap is growing.

Free Exchange writes that Americans have traditionally been inclined to embrace the idea that dividing the pie equally is less important than increasing the total size of the pie. But if the lower 50% to 80% of the income spectrum finds, over a period of decades, that their slice keeps shrinking while the pie gets bigger, they will eventually start demanding more equal slices, whether or not that means smaller pies. If we don't find ways of redistributing national income that don't hurt growth, we're going to end up with ways of redistributing national income that do.

Inequality vs. unemployment

Ezra Klein writes that income inequality is easy to worry about. It offends our moral intuitions. Its tears into the fabric of the American dream. But is inequality really the country’s most pressing problem? Imagine you were given a choice between reducing income inequality by 50 percent and reducing unemployment by 50 percent. Which would you choose? Joblessness is, however, a harder problem to mobilize a political coalition around. Someone making $85,000 annually can look at the incomes of the top one percent and be angry and scared. The plight of the long-term unemployed and the economy's stubborn refusal to generate catch-up growth are more abstract concerns to someone with a good job. It's harder to build a political movement around the intense pain of the few than the more generalized anger of the many.

Paul Krugman writes that these concerns are complements rather than substitutes. Jared Bernstein writes that demand-side policies that that significantly lower unemployment will also reduce inequality. A major factor driving inequality, particularly earnings’ gaps, is the diminished bargaining power of middle and low-wage workers. In an economy like ours, with little pressure from collective bargaining, low minimum wages, and a large low-wage sector relative to other advanced economies, very tight job markets are about the only friend working families have. Over the period when labor markets were tight 2/3′s of the time, incomes grew together. Over the period when labor markets were tight 1/3 of the time, they grew apart.

Ezra Klein writes that inequality can be attacked in ways that do very little for average workers. By contrast, full employment gives average workers the power to demand a better deal from their employers and thus reduces inequality by giving the working class an overdue raise. Ezra Klein writes that a world in which inequality is the top concern is a world in which raising taxes on the rich is perhaps the most important policy choice the government can make. A world in which growth and unemployment are top concerns are worlds in which very different policies -- from stimulus spending to permitting more inflation -- might be the top priorities.

Paul Krugman writes that many of the participants in our economic discourse start with the working presumption that inequality is a second-order issue, that the effects of rising inequality — to the extent that these effects are considered worth mentioning at all — are minor compared with the effects of economic growth or the lack thereof. This presumption is so ingrained in the discourse that hardly anyone looks at the numbers. But when you do look at those numbers, you get a shock. Even if we restrict ourselves to the period 2007 the numbers suggest that the decline in middle-class incomes owes as much to rising inequality as it does to the depressed state of the economy. And this is true even though we’ve suffered the worst economic crisis since the 1930s!

Wealth inequality vs. income inequality

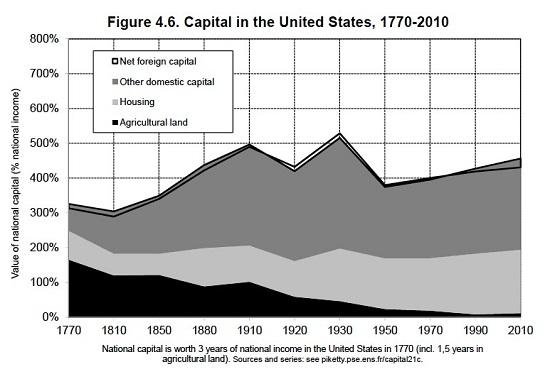

Ezra Klein writes that within the general rubric of “inequality,” income inequality gets a whole lot more attention than wealth inequality. But wealth inequality is much more concentrated and, in various ways, much more dangerous for the social structure. In particular, it’s wealth inequality that really ossifies social mobility. The children of the top one percent only occasionally manage to match their parent’s incomes. But they often receive massive inheritances that grow over time, installing them atop the economic ladder

Thomas Piketty writes the US distribution of income has become more unequal than in Europe over the course of the 20th century; it is now as unequal as pre-WW1 Europe. But the structure of inequality is different: US 2013 has less wealth inequality than Europe 1913, but higher inequality of labor income; in the US, this is sometime described as more merit-based: the rise of top labor incomes makes it possible to become rich with no inheritance

Source: Piketty (2014)