Italy must expand its online franchise

To successfully use emerging technologies to enhance its democracy, Italy must expand the online franchise, by improving broadband access and bringing

“55 years after its promulgation, how would you like to change the Italian constitution?” This is the rather difficult question posed to Italians in the online public consultation that closed in early October. Nonetheless, this attempt to improve the discourse between policy-making institutions and their citizens may have represented a distorted reality, skewed toward the most educated. To successfully use emerging technologies to enhance its democracy, Italy must expand the online franchise, by improving broadband access and bringing down service costs for more Italians – a policy promising attractive side-effects for the Italian economy at a time of challenge.

With the online public consultation on the Italian constitution, two democratic innovations were attempted in Italy. First, using a public consultation to collect citizen opinions over a large and challenging topic instead of a more specific one. Second, releasing results from a public consultation in open data form, under the creative common license CC-BY, which authorizes work sharing and remixing. But to be effective, new democratic channels need to be supported by adequate infrastructure and a consistent digital culture. At the current state, this might not be the case with Italy as showed by data.

Similarly to its European partners, Italy’s most active Internet users are young people between the age of 16 and 35, with around 80% of this group accessing online services regularly. In comparison, the same is true for only 50% of those between 44 and 54 years old (Eurostat). If political interest prevails over lack of digital competence, the survey outcomes could be skewed to the older part of the population and vice versa. The first data released by ISTAT (the Italian Institute of Statistics, that has analyzed survey outcomes) show that the percentage of respondents between 38 and 57 accounts alone for over 40% of the total, and it doubled the percentage of respondents between 23 and 37.

Furthermore, as the consultation has been available online only, significant parts of the population may have been put at a disadvantage when wanting to participate, either due to a lack of competence or simply an absence of Internet access. Italy is affected by a big digital divide. In 2012, household access to broadband was 55% (EU 27 70% in 2012), with regional variations across the country of up to 20%.

The number of respondent types could be narrower than hoped. New instruments of democracy may attract a part of the population less intimate with canonical democratic measures (e.g. vote in the election, debate in public forum), but once again data betray expectations. Most of the survey participants had at least high school diploma indeed. But this could be already foreseen looking at Eurostat data. Those latter show significant positive correlations between education level and internet usage. Not only does this technological advantage has potentially favored those with higher education, but the most educated respondents are also overrepresented among those already exercising their civil rights through traditional tools.

Those threats hang on the validity and efficacy of the survey, where only around 0.4% of people with right to vote has participated. Introducing new democratic measures is a first step into a political and economical modernization path. Nonetheless, to face this challenge Italy needs to guarantee equal and homogeneous access to broadband across the territory for all the citizens.

Some policies to this end have already been adopted. The Italian government launched ‘the National Plan for Broadband’ in 2008, aimed at reducing the infrastructure deficit currently excluding 8.5 millions of people from broadband access. The European Digital Agenda stipulates that all Europeans should have access to Internet above 30 Megabyte per second by 2020. In order to respect these objectives, Italy presented ‘the Strategic Project for Ultra Broadband’ at the end of 2012 and the public investment tranche of 900 million euros for the plan, announced last February, aims to create over 5000 new jobs and raise GDP by 1.3 billion euros.

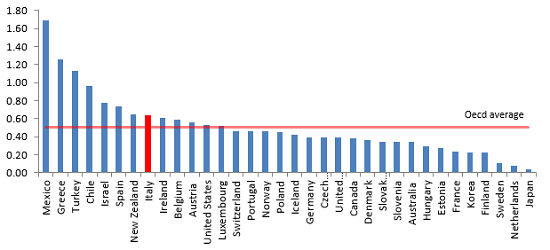

Access does not mean use. Equal broadband access needs to be accompanied by affordable prices. In 2012, Italian citizens paid 25% more than the OECD average for broadband access. The government should work primarily to open the market to more competition, or even to intervene on market failures at the price level.

Source: OECD

Betting on broadband infrastructure is a winning game. Offline, it will significantly increase GDP, the number of jobs and the level of innovation across the country. Online, though the experience from other countries suggests it offers no magic pill, it could improve dialogue with institutions, providing more options for participation, for example also via new e-government tools.