Blogs review: Benign and malign deflation

What’s at stake: As Europe experiences disinflation and worries about deflation risks, a number of policymakers have advanced the idea that defla

What’s at stake: As Europe experiences disinflation and worries about deflation risks, a number of policymakers have advanced the idea that deflation is not necessarily a bad thing. Deflation, it is sometimes argued, increases the purchasing power of those with fixed incomes. Deflation is also good when associated with positive supply shocks as several historical episodes suggest.

Europe and the zero Rubicon

Ambrose Evans-Pritchard writes that if Europe's elites seem nonchalant about the deflation threat staring them in the face, it is because they do not share the Anglo-Saxon and Japanese orthodoxy that letting it happen is an unforgivable policy failure.

Paul Krugman finds it depressing that even Mario Draghi says things like “the fact that inflation is low is not, by itself, bad; with low inflation, you can buy more stuff. ” Don’t we teach students in Econ 101 exactly why that’s a naive fallacy, that lower inflation also means lower growth in earnings, and that the cost of inflation has nothing to do with reduced purchasing power? Krugman also picks up on the statement that “[deflation] is what we have to fear.” Wow. Maybe not in Econ 101, but I thought every professional economist understood that there isn’t a red line at zero inflation, so that low inflation becomes a potential problem if and only if it crosses zero.

Dean Baker writes that the decline in the inflation rate from a low positive to a low negative is a non-issue. The inflation rate is already lower than would be desired, any further fall makes matters worse, but crossing zero means nothing. Accelerating deflation could be a problem, but we have seen exactly zero instances of this phenomenon in the last 70 years in wealthy countries. Paul De Grauwe notes that the consumption-postponement effect does require prices falling. Only if consumers actually expect prices to decline will it start operating. But the debt deflation dynamics (and the real interest rate channel) is already working since this effect does not crucially depend on inflation being negative. It starts operating when inflation is lower than the rate of inflation that was expected when debt contracts were made.

Good and bad deflation: then

Gary Shilling writes that there is an important distinction between good deflation caused by excess supply and bad deflation created by deficient demand. Good deflation is the result of new technologies that power productivity and output as the economy grows rapidly and as supply outpaces demand. The bad kind stems from financial crises and deep recessions, which increase unemployment and depress demand below the level of supply.

Ambrose Evans-Pritchard reports that the BIS study by Claudio Borio and Andrew Filardo shows that much of the 19th century was an era of "good deflation": gently falling prices amid productivity gains and flourishing world trade. Britain was in deflation for 51 years between 1801 and 1879, the era of British economic ascendancy. German prices fell 2% from 1880 to 1913 yet catch-up growth was a blistering 4% on average. But you can cherry pick centuries to make any point you want, and it is highly suspect to lump together chunks of time that have all kinds of ups and downs within them and lose all historical texture. The 1770s tell a very different tale. Britain imposed ferocious deflation on the North American colonies after the debt build-up of the Seven Years War, triggering a depression that caused penury across the plantations of Virginia and the Eastern seaboard. It poisoned feelings on the eve of the Revolution.

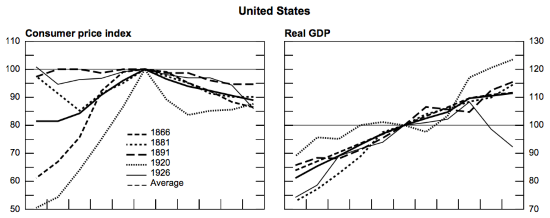

Source: Claudio Borio and Andrew Filardo. Correction: The graph refers to the 1929 episode, not 1926.

Frances Coppola writes that comparing the late 19th century with now is comparing apples and pears. During the Long Depression, the whole Western world was using gold as its currency, though sometimes with silver too. It was the period of the classical gold standard, which ended in 1914 with the financial crisis that preceded the outbreak of World War 1. Using a commodity such as gold as money means that the quantity of money in circulation remains fixed unless more gold coinage is produced. A falling general price level is therefore a sign that the economy is GROWING. More – or better – goods and services are being produced relative to the amount of money in circulation: the value of money rises and the price of goods and services falls. This is “benign” deflation.

Paul Krugman writes that the main case for arguing that deflation is OK is economic growth during the late 19th century. But this is a wrong model because the global situation was conducive to a high natural real rate of interest, making mild deflation much more sustainable than in today’s world. The late 19th century was marked by rapid population growth in the “zones of recent settlement”. In the United States, population grew 2 percent a year from 1880-1910, sustaining high investment demand. And the zones of recent settlement also offered an outlet for very large capital outflows from Europe.

Good and bad deflation: now

Claudio Borio and Andrew Filardo write that the extent to which any future deflationary episodes should raise policy concerns would depend very much on the nature of the corresponding deflationary pressures and the broader economic context in which they took place.

Lars Christensen writes that the economic development in Europe in the last five years has been characterized by very weak demand development. It has created clear deflationary trends in several European economies. That certainly has not been good. It has been a bad deflation. However, the recent decline in European inflation we have seen is primarily a result of falling oil prices – that is a good deflation, which in shouldn’t be a worry.

Reza Moghadam, Ranjit Teja, and Pelin Berkmen write that you can have too much of a good thing, including low inflation. Very low inflation may benefit important segments of the population, notably net savers. But in the current context of widespread indebtedness problems, it is working to the detriment of recovery in the euro area, especially in the more fragile countries, where it is thwarting efforts to reduce debt, regain competitiveness and tackle unemployment. Claudio Borio and Andrew Filardo, however, write that benign deflations might also be those transitory and mild declines in the aggregate price level linked to normal cyclical downturns in a low-inflation environment.