Fact of the week: Russia sanctioned from all sides

Yesterday, the EU introduced new sanctions targeted at specific sectors of the Russian economy. This came one day after an international arbitration c

Yesterday, the EU introduced new sanctions targeted at specific sectors of the Russian economy. This came one day after an international arbitration court in The Hague had decided for an unprecedented ruling related to Yukos, an oil company with a very controversial fate.

On Monday a Tribunal of the Permanent Court of Arbitration in The Hague ruled unanimously that Russia shall pay 50 billion USD to shareholders of Yukos, which back in 2003 used to be Russia’s biggest oil company. It “used” to be, because Yukos actually does not exist anymore. It was seized by the Russian state ten years ago, after the imprisonment of its principal and controversial shareholder, Mikhail Khodorkovsky.

At the time of his imprisonment, Khodorkovsky happened to be Russia’s richest man, with a fortune estimated by Forbes to be around $15 billion in 2004, and quite outspoken. In October 2003, he was allegedly seized by “masked agents” aboard his corporate jet during a refueling stop in Siberia and convicted of theft, tax evasion and money-laundering in 2005. After serving 10 years in jail and he was pardoned by Putin in 2013.

Source: The Economist

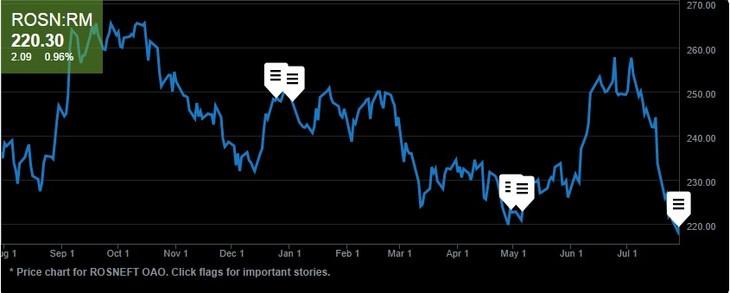

After Khodorkovsky’s arrest, Yukos was broken up and nationalized, and most of its assets were transferred to Rosneft, the state-owned energy group which is by the way already on the US blacklist and now may be hit by EU sanctions too. The chart above effectively summarizes the share price development in these two years.

More precisely, the FT reports that YNG - Yukos largest oil producing unit - was acquired by a company called Baikal Finance Group, which was established two weeks before the auction and whose registered address seems to have been that of a bar in a town north of Moscow. YNG was allegedly worth ⅔ of Yukos total value (around 40 USD billion), but its core assets were sold to Baikal at 9.35 USD billion. Baikal had a capital of $359 only, but it managed to make the cash deposit of $1.77bn required to register for the auction. Rosneft then acquired the company following the auction.

Anders Aslund’s explains in detail the origins and bases of the case. The arbitration is in fact based on the Energy Charter Treaty, concluded by about 50 European countries in 1994 and entered into force in 1998, which contains strong guarantees against confiscation. Russia happened to have signed but never ratified it. The signature however provided sufficient justification for this case. In 2009, Russia withdrew from the Energy Charter Treaty just after its jurisdiction for this case was accepted by The Hague court. As a consequence, no new case can be raised against Russia on the basis of the treaty, but this one could continue. The defendant was the Russian Federation whereas the main claimant was GML Ltd., which owned 60 percent of Yukos and was formed by Mikhail Khodorkovsky and partners in 1997. The primary beneficiary of trusts that own 70% of GML is Leonid Nevzlin, partner of Khodorkovsky, to whom Khodorkovsky gave up his dominant share in 2005. The original claim was $103.5 billion.

The FT has an interesting collection of quotations from the Yukos judgement, which questions the means and motives of the Yukos affaire.

The arbitrators explicitly states that “The decision to seize and sell Yuganskneftegaz, which accounted for approximately 12% of Russia’s oil output and whose value on any estimation dramatically exceeded that of the alleged tax debt, can only be reconciled with a desire to destroy the Company and appropriate its core assets”. And again that “the desire of the State to acquire Yukos’ most valuable asset and bankrupt Yukos. In short, it was in effect a devious and calculated expropriation by Respondent of YNG”.

Concerning the company that took over YNG, the judgement points out that “one of the most opaque facets of the YNG auction is the identity of Baikal, the sole and successful bidder at the auction which was acquired by State-owned Rosneft three days after its successful bid. [...] It was obviously a vehicle created solely for the purpose of bidding for YNG at the auction.”

The most important link, however, is the one between Baikal and Rosneft. The judgement states that “Rosneft’s purchase of the YNG shares from Baikal was an action in the State’s interest, the inference being that the State, then 100 percent shareholder of Rosneft, the most senior officers of which were members of President Putin’s entourage, directed that purchase in the interest of the State. It follows that that act, as well as the auction of YNG shares that underlay it, is attributable to the Russian State. ”. FT Alphaville has a must-read account of how it has actually been the loose lip of Putin himself to lead the arbitrators to the conclusion that Rosneft was acting on behalf of the State.

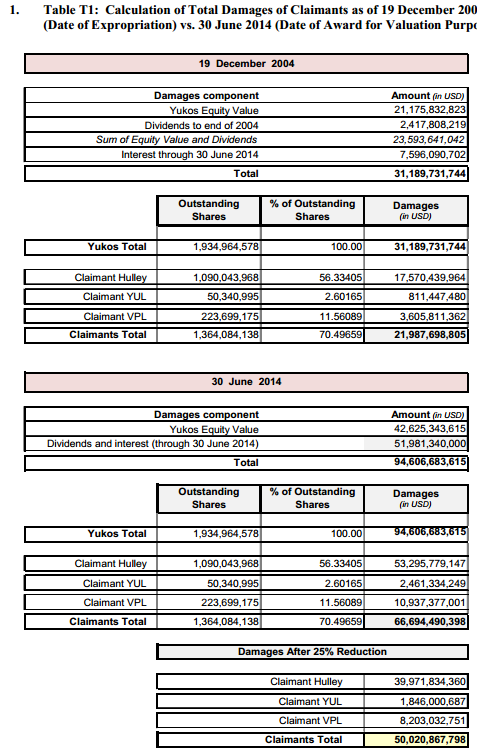

Long story short, Yukos former shareholders were awarded 50 bn USD in damages to be paid by the Russian Federation. The award is largest than any prior international arbitration award (20 times the previous record, to be precise) and large for Russia, as it accounts to almost 2.5% of GDP, 11 per cent of Russia’s foreign exchange reserves and 10 per cent of the national budget. (see figure below for a detail account of how the 50 bn are derived).

Source: FT

In what looks like a masterpiece in perfect timing, this comes one day before the EU also agreed a package of additional restrictive measures against Russia on the reason of its role in Crimea and Ukraine.

According to the statement sanctions will be “targeting sectoral cooperation and exchanges with the Russian Federation. These decisions will limit access to EU capital markets for Russian State-owned financial institutions, impose an embargo on trade in arms, establish an export ban for dual use goods for military end users, and curtail Russian access to sensitive technologies particularly in the field of the oil sector”.

The phase-three sanctions details published by the Council states that:

- EU nationals and companies may no more buy or sell new bonds, equity or similar financial instruments with a maturity exceeding 90 days, issued by major state-owned Russian banks, development banks, their subsidiaries and those acting on their behalf. Services related to the issuing of such financial instruments, e.g. brokering, are also prohibited.

- An embargo on the import and export of arms and related material from/to Russia was agreed. It covers all items on the EU common military list. The measures will apply to new contracts and not existing deals. This point that has been quite controversial, due to France’s decision to honour an existing contract to sell Mistral-class helicopter assault ships to the Russian navy.

- A prohibition on exports of dual use goods and technology for military use in Russia or to Russian military end-users. All items in the EU list of dual use goods are included.

- Exports of certain energy-related equipment and technology to Russia will be subject to prior authorisation by competent authorities of Member States. Export licenses will be denied if products are destined for deep water oil exploration and production, arctic oil exploration or production and shale oil projects in Russia.

These restrictions will now be formally adopted by the Council through a written procedure and they will apply from the day following their publication in the EU Official Journal, which is scheduled for late on 31 July.

The sky is getting greyer over Moscow and the number of issues that could keep policymakers awake at night is growing, on both fronts. The Yukos ruling hit Russian stocks, and the dollar-denominated RTS index of Russian shares closed down 3 percent according to Reuters. Rosneft shares were down 2.6 percent and Rosneft Dollar Bonds Slump to 12-Week Low (see below).

Source: Bloomberg

The FT reports one person close to Mr Putin saying the Yukos ruling was insignificant in light of the bigger geopolitical stand-off over Ukraine. “There is a war coming in Europe,” he said. “Do you really think this matters?”. Hopefully, at least the first part of the statement will not prove right.