Looking past the (West’s) end of the nose

Following the recent IMF annual meetings, and the coincidental declines in global stock markets, gloom is back about the state of the world economy. W

Following the recent IMF annual meetings, and the coincidental declines in global stock markets, gloom is back about the state of the world economy. While there is some evidence of a recent slowdown in the world economic cycle, what is being largely ignored is that the underlying growth trend of the world economy itself is actually rising.

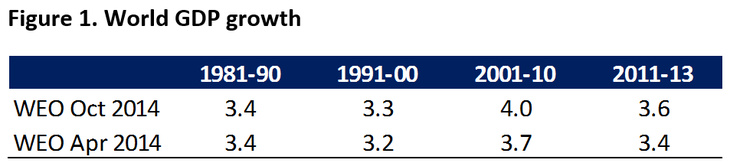

Source:IMF, own calculations

Many observers seem to be unaware of the fact that the world economy grew faster in the decade 2001-10 despite the fact that there were two major global economic crises, the bursting of the dot-com bubble in 2000-01 and the global credit crisis in 2008-09. According to revised IMF data (displayed in Table 1 above), which incorporates the recent new PPP estimates from the International Comparison Programme (ICP), world GDP growth in 2001-10 rose by around 4.0 percent, up from 3.7 percent based on the old weights, which was already stronger than generally appreciated. This GDP growth rate was already higher than the 3.4 and 3.2 percent growth of the previous two decades, and of course, the higher growth rate reflects the stronger weights of the rising emerging economies such as China and India, and their own stronger growth rates. What is probably even less known is that despite the various challenges around the developed and developing world so far this decade, in the years 2011-13, world GDP growth was around 3.6pct, which although down from the last decade’s heady growth, is also higher than the two previous decades.

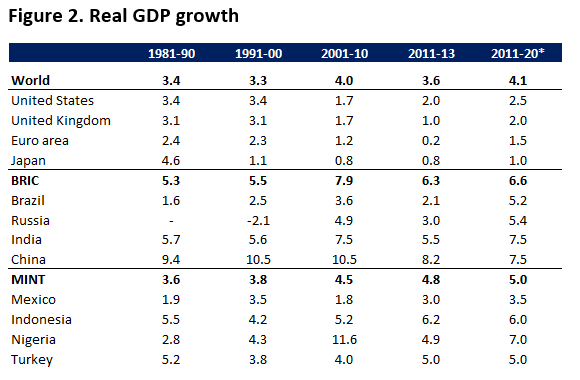

The table 2 below shows the growth rates by decade since the 1980’s for major regions, the world in general, as well as this decade to date, and what we have been assuming the world’s potential would be for this full decade, 2011-20.

Source:IMF, own calculations

Note: *forecasts

What is clear is that the stronger underlying trend is due to the rising weight of the so-called BRIC countries, especially China, and to a more modest degree, the next largest group of emerging economies, that I call the MINT countries. While all four of the BRIC economies have slowed decade to date, the MINT countries have actually accelerated as a group, and seem set to have a stronger growth rate this decade than the last. While the BRIC countries will experience slower growth this decade, it is only really Brazil and Russia that have significantly disappointed, which in both cases, reflects their own significant challenges, of which at the core, is their excessive dependence on commodities and the benefit of rising prices. While India has been softer than assumed so far, there is a reasonable chance that economic growth will accelerate again under the current Indian leadership. As far as China is concerned, while it is likely to continue to show softer growth than the previous decades, for many, including myself, this growth is not anything less than assumed. In fact, as can be seen, it is the one country within the BRICs that decade to date has grown stronger than assumed, despite slowing. And the rising weight of China, now bigger than the US in PPP terms, contributes more and more to world GDP growth.

Even the IMF itself appears to refer to disappointments about the emerging world, suggesting that their over prediction of world GDP forecasts for each of the past 3 years is greatly due to excessive optimism about the larger emerging economies. That might be true for Brazil and Russia, but hardly elsewhere.

Looking at the so-called developed world, relative to their underlying trend, it is hard to express too much disappointment about either of the US or UK, nor indeed Japan. Decade to date, Japan has grown close to its assumed trend, and although each of the UK and US has currently grown by less than the decade’s assumed trend, their current 2014 is above that assumed, and another year similar to this one for both , would take them close to trend.

What is also the case, that seems to be often overlooked by those talking about the persistent disappointments, is as pointed out, this decade to date is –so far- higher than both the 1980’s and 90’s despite the adjustment challenges post crisis. If it is indeed the case that some pessimists argue, that the absence of the unconstrained credit binge of the “Noughties” is hindering growth, it is surely quite encouraging that growth although softer than that decade is, at least globally, higher than the previous two. Indeed, if the strength of the 4pct growth of the previous decade was partially due to the excesses that led to the global credit crunch, and not sustainable, seen in this light, the growth maintained from 2011-13 is quite respectable.

A further substantive point which many pessimists seem to overlook, is that each of the US and China has moved to a much more desired external balance of payments position than existing before the crisis, with the US current account deficit likely to be close to 2 percent of GDP in 2014, down from around 6.5 percent in 2008. China has seen its current account surplus drop sharply from close to 10 percent of GDP to somewhere between 2-3 percent of GDP. For both these economies to make such an adjustment and for their own growth rates to have performed in the manner they have is quite impressive.

What is more genuinely disappointing is that the Eurozone has shown such persistently weak growth this decade, significantly below its assumed- weak- trend, and is the main explanation as to why global GDP growth has stayed below its- rising –potential. Moreover, unlike the US or China, the Eurozone has seen its external current account surplus widen significantly, probably a partial reflection of the weakness in domestic euro area growth.

For the world as a whole to achieve its better BRIC and MINT induced potential, it can only occur if Euro Area policymakers can be more determined to pursue policies that both boost their cyclical economic performance, and perhaps do more to boost their own weak underlying trend.