The world is ready for a global economic governance reform, are world leaders?

A survey of G20 practitioners reveals how, notwithstanding the post-crisis loss of momentum, the G20 is still considered a useful forum of discussions

Bottom line: A survey of G20 practitioners reveals how, notwithstanding the post-crisis loss of momentum, the G20 is still considered a useful forum of discussions. While changes to its composition and workings would be accepted (to varying degree), major revisions in global economic governance are ruled out, bar in case of another major crisis. Our claim is that, at a time of major rebalancing in world economic weight, intransigence by the detainers of power in (what now looks like) an old global governance framework will imply a fade in relevance of the Bretton Woods institutions and G-fora, and their replacement by new avenues of coordination and discussion.

The 2008 financial crisis has markedly changed the landscape of global economic governance. Fora like the G20, which had existed since the Asian financial crisis with a limited discussion role, suddenly were elevated to ‘global economic steering committee’. Since then, however, it seems as though the G20 has somewhat lost direction and momentum. As the most acute phase of the global economic crisis has passed, heads of state and government have had less need to act in unison and rather returned to focus on their national agendas. To some extent, it naturally follows that the focus both on and of the G20 has become less. However, we need effective global governance permanently, not just in crisis. And this is true for the G20, as it is for the G7/8[1] and the IMF.

In a recent paper, we argued that, given the fast-paced changes in global wealth creation and trade patterns, global governance will have to adapt much more significantly and quickly or else risk becoming insignificant. On top of calling for a far-reaching IMF quota reform (going beyond the pending 2010 revision), we argued that it would make sense for euro area countries to have a united global representation. This could happen in a ‘revised’ G7/8, hence opening up space for China and other emerging economies. If there were a more representative G7/8, it would immediately follow that the G20, close to its current membership group, could survive, although it would not be required to have such a demanding role that it is does currently. As such, a smaller, equally representative G7/8 could be more effective than the representative but cumbersome G20.

Against this background, we decided to test many of these claims with G20 practitioners, former Sherpas, and senior government officials involved with the preparation of the G20. To this purpose, we constructed and administered a survey, with the aim of sensing the degree of acceptance of the need and feasibility of a reform of global economic governance.

The survey was administered via e-mail or phone between the 7 May 2014 and 20 June 2014 to the Sherpas of the countries that belong to the G20 Permanent Members grouping, and to the Invited Members, for which contact details were found (see Table 1). This was complemented by a group of 9 high-level global governance experts and former G20 practitioners. Of the 34 people contacted, 23 agreed to participate in the survey. In the end, 15 questionnaires were returned completed.

Table 1. List of G20 participants

|

Permanent Members |

Invited Members[2] |

|

|

Argentina Australia Brazil Canada China EU France Germany India Indonesia |

Italy Japan Mexico Russia Saudi Arabia South Africa South Korea Turkey United Kingdom USA |

UN OECD World Bank Spain[3] ILO FSB Singapore Brunei Ethiopia Senegal Kazakhstan IMF WTO |

Source: http://en.g20russia.ru/

The survey was conducted under full anonymity, as its purpose was not to detail specific governments’ positions, but rather to build on the expertise of insiders and former practitioners in analysing the problems the current global economic governance framework faces, and verify the conditions for and likelihood of reform.

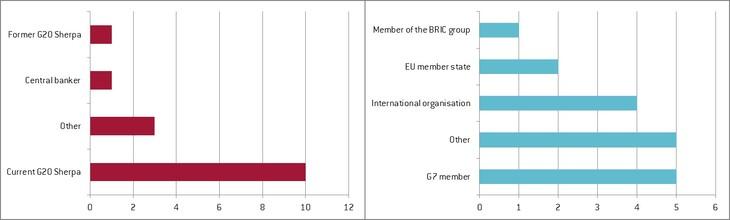

All in all, while participation was not complete, the response rate was acceptable, bearing in mind that most Sherpas are deputy foreign/finance ministers, top-ranking government officials, ambassadors, heads of cabinet, individuals that tend to be rather short of time. As detailed by Figures 1 and 2 (below), a diverse range of participants replied, both based on post-holdings and geographical origin. As such, we believe our survey to be broadly balanced in composition and to give a fair analysis of the different streams of thought within the G20.

Figure 1 and 2. Respondents’ current post (lhs) and geographical origin of employing institution (rhs)

Note: Geographical origin allowed for multiple answer.

Source: Bruegel.

Survey Results

The first question we posed in our global governance survey was whether with 19 countries, a two-headed EU, permanent guests, countries invited on behalf of regional groupings, and international organisations, the G20 is too large a group to decide on macroeconomic and monetary issues, for which only few countries are relevant. A large majority of G20 practitioners proved to disagree with this statement. Some of the survey participants who disagreed backed their take by stating:

“I see no evidence the size has made discussions too unwieldy. However, I think it could be better to limit the membership to G20 members instead of also having the IOs and invited countries present.”

Others agreed completely:

“The group is too large and not truly reflective of what would be needed from a representation point of view to 1/ debate and find consensus around set of actions and/or 2/ decide on a set of actions. There are several difficulties with membership: too many Europeans, Argentina not relevant, Saudi Arabia a one-issue member; Africa under-represented.”

Finally, a central banker noted that:

“[the G20 is indeed too large a group] especially for monetary issues. It is possibly the right grouping for regulatory issues. Only group beyond G7 that is good (for monetary matters) is that of the G10 central bankers[4], which meets (informally) in Basel, and this is good, and very open. For example, in such setting the Fed communicated to everyone (including the Indians…) in advance its intention to start tapering QE.”

We then asked survey participants whether they thought the G20 to be an effective forum of deliberation on global economic issues in non-crisis times. Here the picture was a bit more mixed but still with two thirds of participants positioning themselves in the ‘Yes’ camp.

Notably, a survey participant stated:

“The definition of effectiveness should be adapted to the current global economic context. It is usually during a crisis period that countries are more incentivised to act in the interest of the “common good” and move faster towards policy coordination. Therefore, the impact and magnitude of the measures taken by G20 are unlikely to be the same in a crisis and non-crisis period. Similarly, the issues that the G20 is best positioned to take on will also depend on the global economic context. In a non-crisis period, focus should be placed on medium-term agenda that can increase the trajectory of global growth on a sustainable basis, such as enhancing trade, investment and infrastructure financing. The effectiveness of a forum is not necessarily determined by the number of participants alone, but also contingent on other factors, such as how well each participant can contribute to the conversation and the ability of the Chair to steer discussions. An effective G20 in a non-crisis period would be able to coordinate meaningful solutions to medium-term issues through robust debates and exploration of constructive ideas.”

On top of this, it was also noted that:

“The time of diplomacy is different from that of financial markets. There is less urgency now. Macroeconomic coordination is complex and unchartered water, but things are moving.”

However, a former G20 Sherpa noted how:

“[the G20] is the best forum for deliberating on global economic issues, provided the membership is adjusted; but it lacks effectiveness: it should have a greater focus on intimate discussions among leaders with less officials around. In many delegations there is a dis-function between Sherpas and finance Sherpas. Also, the agenda has grown too wide.”

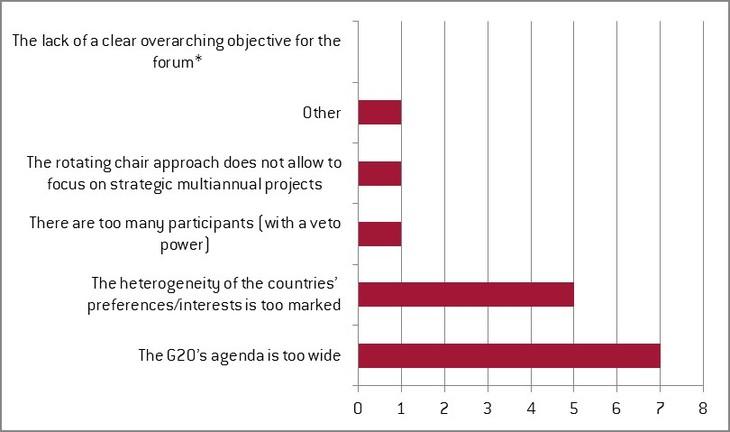

This statement connects us nicely to the next question posed, namely regarding the main element potentially hampering the effectiveness of the G20. Results are displayed in Figure 3, below. Respondents seemed to widely agree on the fact that the G20’s agenda is currently too wide. Furthermore, the heterogeneity of interests and preferences of countries involved seemed also to contribute significantly in hampering the G20’s effectiveness. Interestingly, among the “other” reasons, the fact that Sherpas are not sufficiently empowered to act was mentioned.

Figure 3. Which of the following is the main element hampering the effectiveness of the G20?

Note: * In theory, “achieving strong, sustainable and balanced growth for the global economy” – which is admittedly very broad.

Source: Bruegel

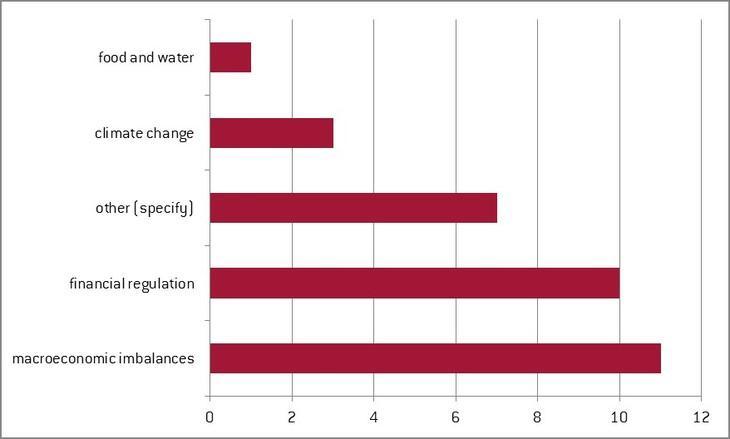

Following up on this, we asked survey participants directly whether the G20’s agenda should be narrowed down and, if so, along what lines. Whereas there was almost unanimity (14/15) on the need to restrict the focus of the G20, survey participants had very different views regarding the topics on which the forum should concentrate.

Figure 4. On which topics should the G20 focus?

Note: Multiple answers allowed.

Source: Bruegel

Interesting thoughts were shared under the ‘other’ category (see Table 2, below). Some survey participants highlighted how a narrow agenda should be set every year, whereas others focused on the operations of the working groups.

Table 2. Other elements on which the G20 should focus

|

|

Specifications of 'other' |

|

1 |

The issue is not to limit the agenda permanently, but focus on a few issues at a time and discontinue working groups when they have finished a specific task instead of giving them new mandates, which may be less relevant. |

|

2 |

Essentially it should be about economic governance, climate being an integral part of it. |

|

3 |

Supporting global growth. |

|

4 |

Development. |

|

5 |

Trade, Investment, Infrastructure. |

|

6 |

Select very small number of specific subjects on a yearly basis. |

|

7 |

Trade. |

Source: Bruegel

As various degrees of dysfunctionality were identified, we then turned to questions regarding ways of tackling it. Commentators in the past have claimed that tweaks in the governance of the G20 (including the establishment of a permanent secretariat, better streamlining of internal processes, etc.) could improve its effectiveness, as its weaknesses are not structural in nature. 60% of our survey respondents disagreed with this claim. One survey participant mentioned that a secretariat would just add to the bureaucracy of the forum, and there is no need for it. S/he then added that:

“[within the G20 setting] Nobody listens to the IMF itself, so it is not clear why they would listen to the secretariat.”

The G20 being merely a forum of discussion with no coercive powers, we turned to test the idea that peer-pressure is significantly felt and is effective at nudging country leaders into policy action. Almost the totality (14/15) of survey participants agreed with the proposition that peer-pressure within the G20 can push a sovereign government to take actions based on previously agreed commitments. In the discussion that ensued, survey participants expressed a somewhat milder (positive) judgement:

“Taking policy actions based on previously agreed commitments will be essential to the credibility of the G20, and G20 members need to recognise this as a group. The Accountability Assessment exercise and the peer review process in the Framework Working Group are good steps, but as sovereign states, countries retain the right to take actions aligned with their national interests. It remains uncertain whether peer pressure amongst G20 members would be sufficient to affect agreed policy changes across the board, such as the standstill on protectionist measures. Having said that, the G20 has achieved success in certain areas, such as financial regulation.”

In this respect, we note that several respondents highlighted financial regulation as a field in which peer pressure has had a significant impact within a G20 context.

Finally, two survey participants detailed the requirements for peer-pressure to succeed:

“yes, if done intelligently and in a focused manner, i.e. around a limited set of issues; collective behaviour in resisting temptation to go protectionist was a clear example of this; many countries sued the G20 commitment to resists political pressures at home.” “This is how the OECD is functioning (peer review/peer pressure in the context of its Committees) and this is working pretty well with concrete outcomes, e.g. the convergence of policies towards the best practices. But peer-pressure, to be effective and yield concrete results, requires initial and specific commitments by members of the Group – that are specific and assessable, that can be monitored and to which countries can be held accountable. To make such commitments, countries need to make compromise and look beyond their immediate short term interest. This requires trust among members, a zone of comfort and a degree of like-mindedness, which G20 members may not have reached as yet.”

Along the same lines, we then asked survey participants whether, more in general, some national-level policies in the past had been taken as a consequence of agreements within the G20, and would not have taken place without this forum. Again, the quasi-totality of survey participants (14/15) was positive in its assessment of the G20’s capacity to nudge countries into action. G20 practitioners clarified how:

“G20 commitments have a real domestic impact in member countries. […] it is worth noting that countries have decided to join international instruments as a result of their G20 membership. For instance, Saudi Arabia decided to ratify the United Nations Convention against Corruption (UNCAC) largely as a result of its engagement with the G20 Anti-corruption Working Group.”

Some enthusiastic detailed the dossiers on which G20 peer-pressure had been successful:

“Yes, definitely, the international tax transparency agenda (fight against tax heavens and bank secrecy) and the fantastic results achieved in this domain by the G20 are the best illustration of this. The AMIS – to reduce food price volatility and improve food security - is also a good example.”

Even the sceptical voices, accepted a role to be played by G20 peer-pressure and commitments:

“It seems more plausible that domestic interests remain the key reasons for the adoption of national-level policies. Such interests might include relations with key international counterparts, therefore concluding that these policies were a consequence of agreements within the G20 might not be entirely accurate. Having said that, it is indeed to the G20’s credit that certain issues are placed in the limelight, so that countries would accelerate the progress or implementation of such policies. In the case of financial regulation, the G20 empowered an international body – the Financial Stability Board – to coordinate international policy development, and monitor implementation of G20 commitments.”

Finally, a central banker noted that peer pressure is much more effective when pursuing stimulus packages than for policies of economic restraint.

At this point, we turned to test the palatability and feasibility of the idea presented in O’Neill and Terzi (2014) of having a ‘revised’ G7/8 (where euro area countries would have a unique representation, opening up space for China and another emerging economy) as an alternative prime forum on global economic issues. In fact, a large majority (73%) of G20 Sherpas and (former) practitioners expressed their scepticism towards this solution. In the discussion that ensued, however, many respondents moderated their dissent:

“There is a need to have a more rational representation of the EU in the G20 and there is a need to have a smaller number of members but it will have to be bigger than the G8 and smaller than the G20.”

Another (dissenting) respondent proved to be in favour of an even smaller prime forum:

“Would use space to reduce the number of seats, not to add new members. Could also use international and regional bodies more effectively to represent those not at the table.”

Others made a more wholehearted plead in favour of the G20 in its current setting:

“The “steering committee” of the world economy needs the perspective of countries that are not necessarily systemic (such as South Africa that somehow gives an African perspective on world economic affairs). A forum of global economic governance needs to balance between: legitimacy – ensuring that all major economies work together on an equal footing in international organisations and effectiveness – the ability to cover the right issues, forge a strong common consensus and effectively co-ordinate across different fora. This is important for its credibility and influence at the global level. Also, the present G20 format provides an opportunity for a genuine joint learning process between advanced and emerging economies and a full-fledged two-way exchange of experiences among them.”

Finally, some of the dissenting voices based their position more on the feasibility of the option, rather than on the palatability:

“We should take note that euro area countries do not necessarily have united position on all the issues being discussed in the G20. However, at the same time, it might be worthwhile to consider reducing the number of euro area countries and freeing up space for non-euro area countries in Asia and Africa.”

When asked specifically about the feasibility of creating such a ‘revised G7/8’, 100% of the respondents were negative. In the discussion, some explained that further euro area integration is needed before such a step can be taken.

We then asked (only) non-euro area country representatives whether they would prefer to liaise with a united euro area in global fora. Interestingly, some survey respondents chose not to answer this question. Of those who did, 63% (7/11) expressed a positive answer. Interesting comments ensued:

“When EU members agree, having a large representation around the table plus President of the Commission and Council just means repeating the same arguments over and over again, to the frustration of non-EU players; coherence among EU is to be shaped in Brussels and not at the G8 or G20; when it has not been shaped in Brussels, then the multiple EU representation at the G20 simply show the degree of the disagreement.”

Along the same lines, a BRIC representative explained that:

“Yes [it would be better to liaise with a unique euro area representative], also in the G20. Too many Europeans saying the same thing creates the idea of a false majority in the room.”

However, a G20 Sherpa representing an international organisation highlighted that:

“That would make sense indeed but provided it reflects a genuine unity of view. Otherwise the common representation will lack credibility in the G20 – which would be counterproductive for euro area countries and the G20 itself.”

Finally, a G20 Sherpa clarified that, although the composition of the G20 is dubious (only one African country, only three Latin American, and too many Europeans), the forum has decided to focus on policy coordination, and leave aside discussions regarding membership and/or enlargement.

When asking (only) G7/8 members whether our ‘revised G7/8’ seems sensible as an alternative scenario to the current Group of Seven, which increasingly represents a small club of advanced democracies, three out of five respondents disagreed. Defenders of the current G7/8 highlighted the importance of having a small club of likeminded countries:

“A ‘small club of advanced democracies’ can effectively project authority, unity and vision: very valuable goods. This, without pretence of global governance, which needs close-to-universal representation, and is already the goal of other fora.”

This chimes well with another respondent, who made the point that:

“The current G7/8 framework has its own significance and effectiveness as a small club of advanced economies, where the G7/8 Leaders can have frank discussions on important issues that the international community is facing. It should not be replaced by any alternative framework.”

Moving beyond the G7/8 and the G20, we asked global governance practitioners and experts whether in their opinion the pending 2010 IMF quota reform had gone far enough in rebalancing power between declining and emerging economies. A wide majority of respondents (13/15) agreed that the 2010 IMF reform was now already somewhat outdated. We hence posed the question of whether the implementation of our proposed ‘revised G7/8’ would pave the way for a speedier reform of the IMF. A wide majority of respondents (73%) disagreed, mostly citing the fact that the current reform is being held back by the U.S. Congress and its internal political quarrels, rather than by the G20. However, it was also highlighted how:

“You need the G20, and especially the BRICS, to make the reform advance. G7 would not be really interested in moving it.”

After having underlined the role of the US Congress, one survey participant explained how:

“[...] The IMF has a regular schedule for reviews of quotas and the composition of the Executive Board. The schedule was even accelerated by the G20 in 2010, with a view to bring about a shift in voting share towards emerging markets sooner. It is useful to note that there is a practical limitation to how quickly quota shares of Emerging and Developing countries can be increased. A country can increase its quota share only via its own contributions to the IMF. Countries whose quota shares need to decline cannot be forced to withdraw their contributions. This imposes a mathematical constraint on how much a country’s quota share can rise, particularly when the quota shares of several countries increase at the same time. However, G20 provides additional impetus for reform. 2010 reforms were “historic” in no small part due to the ambition and political commitment from G20.”

To conclude our survey, we asked G20 practitioners and experts under what conditions a far-reaching reform of global economic governance is to be expected, given the current framework (which has at its centre the IMF, WTO, and World Bank) effectively rose from the ashes of World War II and has remained broadly unaltered ever since. Somewhat unsurprisingly, and in many ways, worryingly, the most common response was ‘another crisis’. Strong political will (especially among developed country leaders) was also a recurrent theme. However, other respondents made other valuable points. A current Sherpa offers a dual framework to think about changes in the current global governance framework:

“The current structure of economic governance has never been truly global. It reflects the balance of economic strength that prevailed after the war and in the decades that followed. This balance has shifted more quickly in the last two decades, and the old structure has become increasingly irrelevant. Naturally, those who stand to lose out have resisted allowing the structure to evolve with economic realities. There are two ways a new structure can emerge: by a gradual adjustment from the current state to the one envisioned; or a sudden adjustment in which the old structure is dismantled and a new one constructed in its place. A gradual adjustment is less disruptive. But the longer imbalances persist, the more likely it is that the system becomes unstable and economic multilateralism ultimately disintegrates. In addition, it is important to have an inclusive, open, transparent and merit-based process in selecting the senior leadership of international organisations such as the IMF and World Bank.”

And indeed, some of the survey participants believe that a step-by-step approach will lead to a substantial change in the current framework.

“Time [is needed]. Emerging countries continue to grow at faster rate than advanced one. At some point thing will be reflected in a deeper reform of the current architecture or the creation of a new one, perhaps with new financial institutions outside the control of currently advanced economies.”

Conclusions

All in all, our survey did not really support our policy recommendation for immediate pro-active reform of global governance. Perhaps this is not surprising in view of the fact that most of the participants are actively involved in some aspect of the current governance framework, and institutions tend to self-perpetrate. Nonetheless it was interesting for us to see the general response to far-reaching reform proposals, which go beyond a fine-tuning or streamlining of the internal workings of the current global governance framework.

As it relates to the G20, virtually all respondents answered that the G20 is a useful forum, with many indicating that it plays a positive role. In this sense, the G20 is clearly seen as legitimate by those who participate. A number of participants made it clear however that the G20 agenda is often too diverse and it would benefit from having a more defined focus. Just as interesting, there was not much support for the idea of a devoted secretariat in helping create a regular focus. As could be garnered from the last answer about what would be necessary for further accelerated reform of global governance (answer was overwhelmingly, another crisis), it seems as though G20 participants believe that a crisis forces policymakers to focus on the immediate solutions, and outside of crisis, they will not have the same need or incentives.

When it comes to faster reform of the IMF, as we prescribed in O’Neill and Terzi (2014), very few survey participants believed that the structure of the G20 or G7 was a hindrance, and in fact, it was primarily the inability or lack of desire by the US Congress to ratify already agreed G20 proposals that were holding back any initiatives at faster reform. In this respect, a certain degree of vexation could be sensed among G20 Sherpas and practitioners.

Finally, one of our previous key recommendations that we explored was, that inside the G20, a reshaped G7 should be found in which all euro area members were represented by just one, allowing space for China and other key emerging economies. We did find some sympathy for this idea from non-G7 countries and non-euro area members, perhaps not surprisingly. However, we did not get any voluntary support for such a shift from either euro member countries or other G7 countries, with those that responded actually suggesting that it was impractical to expect such a shift, not least because the euro area member countries still often have different views, and according to some, it is very beneficial still to have an effective group of like-minded advanced country democracies. One respondent pointed out that when it came to monetary policy, as opposed to fiscal and other policy matters, the central bankers gatherings in Basle are quite effective for discussion and, when necessary, advance warning and co-ordination. The fact that this took place with less fanfare was also advantageous.

It seems as though any revamp of the G7/8 is not set to voluntarily happen from within for the foreseeable future. We believe that, at a time of major rebalancing in world economic weight, intransigence by the detainers of power in (what now looks like) an old global governance framework will imply a fade in relevance of the Bretton Woods institutions and G-fora, and their replacement by new avenues of coordination and discussion. In this respect, the recent agreement to establish a BRICS Development Bank is highly symbolic. The world is fast changing and ready for more representative, more effective global economic governance. G7/8 leaders can drive this change, or merely face its consequences.

[1] Throughout the post, we will refer to the G7 or G8 interchangeably, as in this instance we do not wish to enter the discussions surrounding Russia’s role in the Group of Eight following the Ukrainian crisis.

[2] Invited members vary from summit to summit. These correspond to the invitees of the last Summit (Saint Petersburg – September 2013).

[3] Spain is a permanent guest.

[4] The composition of this informal group was not formalised but seemed to include G7 members, China, India, and Mexico.