Monetary vs. fiscal credibility in Japan

What’s at stake: The damage inflicted by the introduction in April of the first major tax increase in 17 years has led to calls for postponing th

What’s at stake: The damage inflicted by the introduction in April of the first major tax increase in 17 years has led to calls for postponing the next scheduled raise in the consumption tax for fear that it would, otherwise, affect the credibility of the monetary regime change. But with a debt load that exceeds 240% of GDP, several commentators believe that backtracking on the consumption tax could cause a fatal loss in Japan’s fiscal credibility.

The funny thing is that both sides of this debate believe that it’s about credibility; but they differ on what kind of credibility

Paul Krugman writes that the funny thing is that both sides of this debate believe that it’s about credibility; but they differ on what kind of credibility is crucial at this moment. Right now, Japan is struggling to escape from a deflationary trap; it desperately needs to convince the private sector that from here on out prices will rise, so that sitting on cash is a bad idea and debt won’t be so much of a burden. The pro-tax-hike side worries that if Japan doesn’t go through with the increase, it will lose fiscal credibility and that this will endanger the economy right now.

The credibility of the monetary regime change

Jacob Schlesinger writes that the anti-deflation quest would be easier if the government focused solely on that goal. It isn’t. The Finance Ministry’s top priority is curbing Japan’s outsize sovereign debt, prompting it to push through a sales-tax increase this past spring and seek another next year—even though the first set back the anti-deflation drive by depressing growth.

Paul Krugman writes that Japan should be very, very afraid of losing momentum in the fight against deflation. Suppose that a second tax hike causes another downturn in real GDP, and that all the progress made against inflation so far evaporates. How likely is it that the Bank of Japan could come back after that, saying “Trust us — this time we really will get inflation up to 2 percent in two years, no, really” — and be believed? Stalling the current drive would cause a fatal loss of credibility on the deflation front. Jay Shambaugh believes the value-added tax is problematic because it makes the inflation data difficult to read.

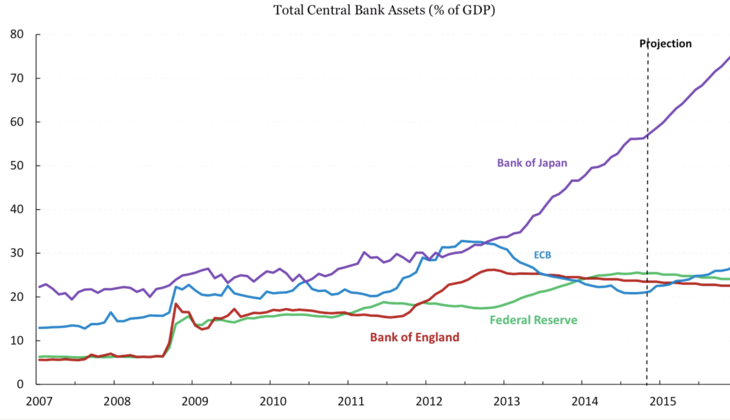

Kevin Drum writes that all three of the biggest central banks on the planet apparently are having trouble hitting even the modest target of 2% inflation. Are they unwilling or unable? Either way, the longer this goes on, the more their credibility gets shredded. In the past it's been mostly taken for granted that "credibility" for central banks was related to their ability to keep inflation low. Today, though, we have the opposite problem.

Fiscal credibility: then and now

There is more art than science in determining what is fiscally sustainable for a large economy with its own currency

Adam Posen writes that there is more art than science in determining what is fiscally sustainable for a large economy with its own currency. Takatoshi Ito has argued that a major reason there has not been a breakdown in or market attack on JGB trading up till now is because everybody knows you could eventually raise taxes. There is this room to raise taxes, in terms of the limited share of tax revenue in national GDP for Japan. But we are reaching the point where it is no longer a question of the Japanese government could do that when needed, but that the government should do that starting now. I do think that there is now a true market risk - not so much in the JGB market but in the Japanese equities market and in the yen exchange rate. Were the Abe government to hesitate too much or fail to commit this fall to raising the tax in 2015 as scheduled, much of the asset price gains seen in Japan since December 2012 would disappear, and credit would be disrupted.

Adam Posen writes that Japan was able to get away with such unremittingly high deficits without an overt crisis for four reasons. First, Japan's banks were induced to buy huge amounts of government bonds on a recurrent basis. Second, Japan's households accepted the persistently low returns on their savings caused by such bank purchases. Third, market pressures were limited by the combination of few foreign holders of JGBs (less than 8 percent of the total) and the threat that the Bank of Japan (BoJ) could purchase unwanted bonds. Fourth, the share of taxation and government spending in total Japanese income was low.

An experiment in fiscal consolidation with full monetary offset

Brad DeLong understands the argument if what is being advocated is not just an increase in taxes but an increase in taxes coupled with full monetary offset in the form of additional monetary goosing. Gavyn Davies writes that under such a scenario the devaluation and monetary easing would compensate for the second leg of the sales tax increase from 8 to 10 per cent due next autumn, so nominal GDP would grow at least at a 3 per cent rate and the public debt to GDP ratio would start to decline.

Mr Abe should instead announce legislation for the tax to go up by one percentage point a year, for 12 years

The Economist writes that Kuroda’s stimulus was intended to make it easier for the prime minister both to carry out structural reforms and also to raise the consumption tax. But private consumption is too weak for the economy to bear a tax rise right now. So Mr Abe should instead announce legislation for the tax to go up by one percentage point a year, for 12 years. The increases should start when the economy can bear it. That will not be next year.

Gavyn Davies writes that following its most recent announcements the BoJ will now increase its balance sheet by 15 percent of GDP per annum, and will extend the average duration of its bond purchases from 7 years to 10 years. This is an open-ended programme of bond purchases that in dollar terms is about 70 percent as large as the peak rate of bond purchases under QE3 in the US.