The ECB’s balance sheet, if needed

In his press conference on November 6th, ECB President Mario Draghi pledged monetary stimulus, although only “if needed.” These words have won Mr

In his press conference on November 6th, ECB President Mario Draghi pledged monetary stimulus, although only “if needed.” His exact statement was: “The Governing Council has tasked ECB staff and the relevant Eurosystem committees with ensuring the timely preparation of further measures to be implemented, if needed.” In response to questions from journalists, he mechanically repeated the phrase, “if needed” four times. A fortnight later—on November 21st in Frankfurt—in a speech that drew much attention for promising bold new action, President Draghi coined a new phrase: “We will do what we must,” echoing his famous “whatever it takes.” He said: “We will do what we must to raise inflation and inflation expectations as fast as possible;” but he repeated verbatim: “the Governing Council has tasked ECB staff and the relevant Eurosystem committees with ensuring the timely preparation of further measures to be implemented, if needed.”

The “if needed” theme appeared earlier on October 9 in a speech Mr. Draghi delivered at the Washington-based think tank, the Brookings Institution. His prepared remarks said: ““We are ready to alter the size and/or the composition of our unconventional interventions, and therefore of our balance sheet, as required.”

the ECB is behind the curve even as a debt-deflation cycle is ongoing in the so-called “periphery.”

These words have won Mr. Draghi many admirers for his determination to move decisively forward. But the actions tell a different story. The “if needed” mantra is only the most recent example of the ECB’s congenital conservatism in dealing with the ever-unfolding crisis. Once again, the ECB is behind the curve even as a debt-deflation cycle is ongoing in the so-called “periphery.” Rather than a central bank that helps revive growth and inflation, the ECB has become a safety net for dealing with near-insolvency conditions. Its coyly-stated target of an additional trillion euros in balance sheet expansion will not occur and, if it does, would have a trivial effect. By consistently using words while failing to act in time, the ECB is eroding its hard-won credibility.

The Eurozone’s Debt-Deflation Cycle

According to the latest Eurostat data, in October, the 12-month average inflation rate in the eurozone was 0.6%; it was 0.3% for Italy, 0.0% for Spain, and -0.1% for Portugal. In his November 21st Frankfurt speech, Mr. Draghi claimed that such low inflation not foreseen. “Last November,” he said, “[inflation] still stood at 0.9%. This was low, but it was generally expected to rise safely above 1% by now.”

The claim that in November 2013 inflation was “generally” expected to rise is puzzling. Already in April, Guntram Wolff warned of deflationary pressures. And by November, futures markets were projecting annual inflation at below 0.9%. The risk of an out-of-control cycle of rising debt and falling inflation was manifest. And since fighting deflation is harder the more entrenched it is, at least one commentator urged prompt action in January this year: “the ECB's insistence on waiting for more evidence of deflation is a dangerous gamble.”

Finally, on June 5th, with mounting evidence that inflation would not turn up on its own, the ECB did announce several new measures. These were intended “to provide additional monetary policy accommodation and to support lending to the real economy.” But did the measures match the task at hand?

- Zsolt Darvas and Pia Hüttl pointed out, the lower policy rate could be expected to have little effect since banks were already drawing down their reserves at the ECB.

- Silvia Merler was skeptical of the “targeted long-term refinancing operations (T-LTROs)” to stimulate lending. Indeed, a Wall Street Journal survey of market participants on September 18th concluded: “Well it seems that not all banks have gone gung-ho for the European Central Bank’s first longer-term refinancing operations, or TLTRO.” Even if there had been more interest, Wolff was concerned that the measure would delay needed restructuring of banks while it did little to improve monetary conditions.

- Finally, Carlo Altomonte and Patrizia Bussoli quickly did the numbers and explained that the highly-touted program for the purchase of asset-backed, or rebundled, securities would make little difference because the size of the asset-backed securities market was too small. More bluntly, Jacques de Larosiere, the former head of the International Monetary Fund, told Reuters on November 20th, “It is a strategy with little prospect of success.” Because the ECB cannot assume the risk of default, it is limited to the purchase of only the safest slices of the already small market for rebundled securities. The ECB’s calls to others with deep pockets for help went, understandably, unheeded. And, as expected, miniscule quantities were purchased in the inaugural round.

Ironically, now that Mr. Draghi is openly concerned about persistent low inflation, he seems to have run out of instruments to counter the tendency. For this reason, it helps him and his colleagues to claim that the June 5th measures will eventually be effective. But just like the forecasts last year projected higher inflation, the new claim has no support in logic or evidence.

For anyone who wants to see it, a debt-deflation cycle is ongoing in the distressed economies. Scary though they are, the focus on the eurozone headline numbers is somewhat besides-the-point. The focus should be on Italy, Portugal, and Spain. In a recent blog post, Giulio Mazzolini and I showed that countries experiencing faster-than-expected increase in their debt-to-GDP ratios are also those experiencing faster-than-expected fall in inflation. In other words, the authorities have very nearly lost control of a process that will become ever harder to manage as it becomes more entrenched. The ECB’s measures are woefully behind the curve.

Is the ECB Irrelevant?

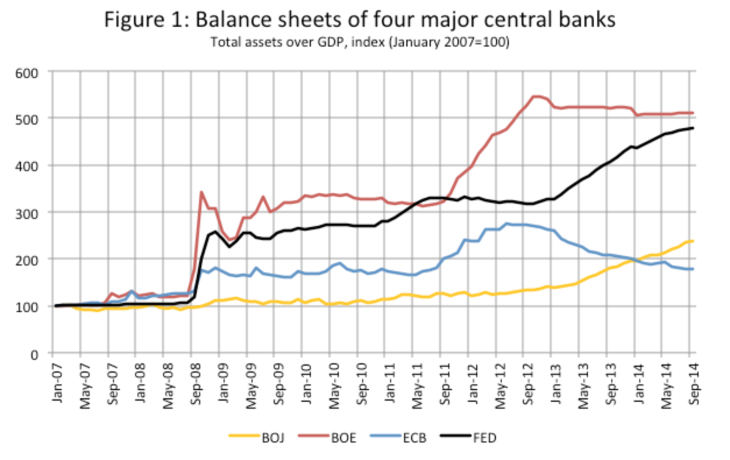

In October 2008, right after Lehman Brothers filed for bankruptcy, the major central banks stepped in to provide desperately needed liquidity to banks and financial markets. Figure 1 shows the expansion of the balance sheets relative to the GDP, normalized to 100 in January 2007 (to eliminate the pre-crisis differences due to variations in financial structures). Even at that existential moment, the ECB’s actions were much more conservative than those of the U.S. Federal Reserve or the Bank of England.

More importantly, a sizeable fraction of the increase in the ECB’s balance sheet was to support the Belgian and French banks, which meant, in effect, Fortis and Dexia. Since Dexia has remained distressed, the support it received was as much to prevent it from filing for insolvency as it was to provide temporary liquidity. This distinction between liquidity and solvency took center stage in mid-2011.

Market’s expectation of how long policy rate will remain low determines the extent of decline in long-term interest rates

A central bank can undertake two principal actions: actively stimulate the economy and passively promote lending (see Hetzel, 2012, especially chapters 14 and 16 for the theory and application to the Great Recession in the United States). Active monetary stimulus of the economy is normally achieved by reducing its policy interest rate. The market’s expectation of how long the policy rate will remain low determines the extent of the decline in long-term interest rates and the consequent increase in investment. When the policy rate falls to zero, the central bank can buy financial assets to directly lower the long-term interest rate, an action often described as “quantitative easing.”

In contrast to active monetary stimulus, the central bank can passively provide funds to banks in the hope they will lend more to release credit constraints on economic growth. However, there is no guarantee that the banks will use their easier access to funds for new lending.

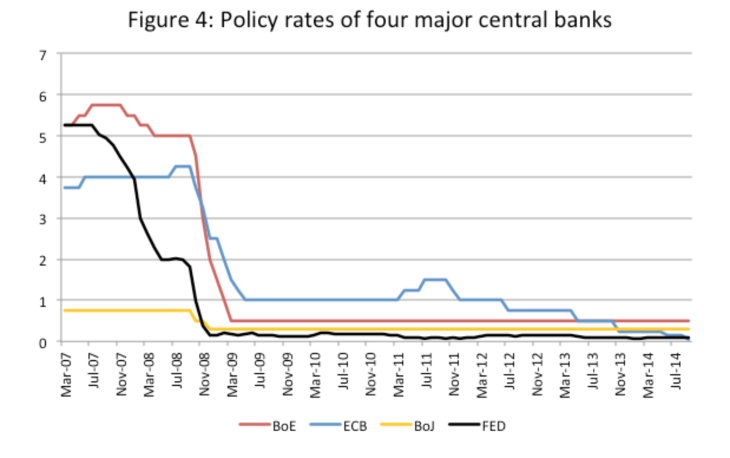

By these conventional categories, the ECB provided no active stimulus. Policy interest rate reductions always lagged behind the fall in activity; indeed, interest rates were raised in 2008 and, more disastrously, in 2011 (Hetzel, 2014). And, the ECB has been virtually absent in the purchase of assets to directly influence long-term rates.

The ECB did provide banks with additional “liquidity.” But, in doing so, it acted in a manner highly unusual for central banks. For an extended period, the ECB’s so-called liquidity operations have, in effect, propped up insolvent banks and have thus been a giant exercise in forbearance.

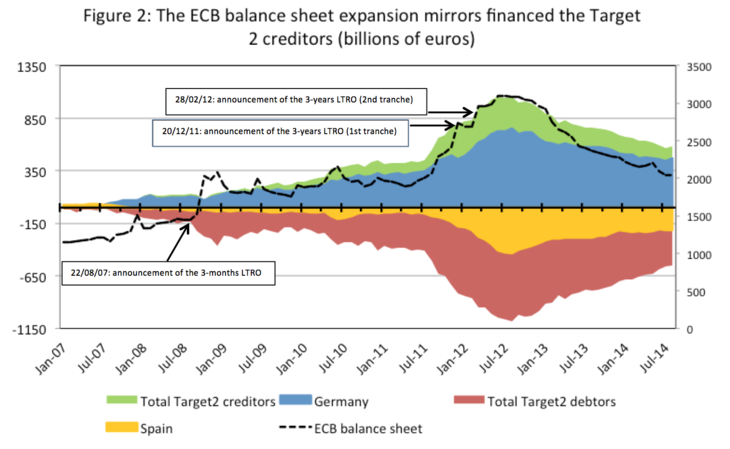

Consider the evidence. The rise in the ECB balance sheet from June-2011 to June-2012 tracks the rise of its so-called Target 2 balances (Figure 2). Before the crisis, banks in the so-called “core” countries had lent large sums to the “periphery” banks. By 2011, the core banks wanted their money back, but the periphery banks, with no alternate source of funding, appeared likely to default on their repayment obligations. Through the Target 2 system, the “core” country central banks lent funds to the “periphery” central banks, who then funded their private banks, allowing the repayment of private periphery debt to the core. Thus, the bulk of Target 2 expansion was used to prevent a wave of defaults rather than provide liquidity to otherwise solvent banks.

Despite many criticisms, the expansion of the Target 2 balances in 2011-12 was appropriate because it prevented disorderly defaults and panic and, hence, maintained financial stability. But that balance sheet expansion provided no monetary stimulus and, importantly, it was only in part a liquidity operation. Because the expansion was not followed by aggressively closing down or restructuring banks—while inflicting losses on their creditors—the breathing space gained was misused to provide extended regulatory forbearance to weak and insolvent banks.

In the United States, the closest similar action was through the purchase of asset-backed securities, which play a more significant role than in Europe. These purchases helped stabilize U.S. financial markets and, unlike the Target 2 expansion, they also helped lower the long-term interest rate and thus provided monetary stimulus. Moreover, in the U.S., the insolvency risks were dealt separately by recapitalizing banks (using fiscal resources) or by closing down and restructuring banks (through the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation).

With time, the Eurosystem’s Target 2 balances have come down, but they remain substantial by any reasonable international norm or the eurozone’s historical standard, pointing to the persistent distress in the European banking system. Even the banks that have stabilized remain weak.

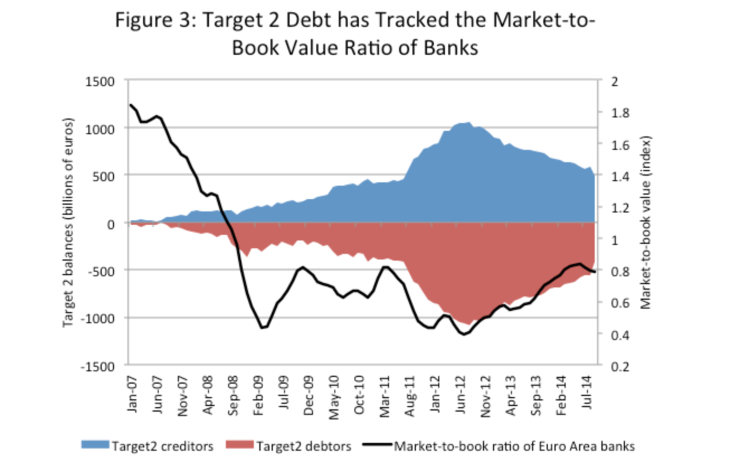

Figure 3 reinforces the view that the key problem lies in viability and solvency of eurozone banks. The repayment of the Target 2 balances has followed the partial recovery of the euro area banks’ market value-to-book ratio (the market value of the banks’ assets relative to the accounting value on their books). Thus, as banks have retrieved some of their lost credibility, they have been able to pay the ECB back.

But even as late as September 2014, the price-to-book value of banks in the Eurozone was still below one. Put simply, several years into the crisis, the financial markets still regard some of the assets on the banks’ books as fictitious. A large segment of the euro area banking system is unable to stand on its own legs and, therefore, requires continued ECB support.

Note: The market-to-book ratio is given by the value of the shares outstanding of the Euro Area banks, divided by the aggregate book value of the same institutions.

Today, the market is reading into Mr. Draghi’s statements an intention of raising the ECB’s balance sheet by 1 trillion euros to about the 3 trillion achieved in June 2012. How meaningful would that expansion be?

even an increase of 1 trillion euros will make the effective ECB stimulus a small fraction of what the U.S. Federal Reserve achieved

If we stipulate that nearly all of the ECB’s outstanding balance sheet is essentially propping up weak banks, then the current effective monetary stimulus—active or passive—is close to zero. Hence, even an increase of 1 trillion euros will make the effective ECB stimulus a small fraction of what the U.S. Federal Reserve achieved. Moreover, since the measures proposed will almost certainly not accomplish the 1 trillion euro target, whatever expansion does occur will have virtually no stimulative effect.

With the Bank of Japan’s balance sheet now exploding, the ECB is set to remain—by far—the central bank with the tightest, most conservative monetary policy among the major central banks. A measure of the ECB’s conservatism is the dollar/euro exchange rate. At about 1.24 (although down from almost 1.4 seven months ago), the exchange rate is about the same as at the start of the crisis. The U.S. economy is about 9 percent larger than its pre-crisis level while the eurozone economy has struggled to reach that level. Looking ahead, the expected growth rates clearly favor a growing U.S. lead. Yet, the euro has remained about as strong as just before the crisis started.

It is as if the ECB has become irrelevant except to limit the fallout from insolvency risks. The ECB’s balance sheet can hold, or promise to buy, obligations that might otherwise not be honored. This was the case with the Target 2 balances. And this was the case also with the ECB’s “outright monetary transactions (OMT) program,” which offered to buy “unlimited” quantities of sovereign debt. For the OMT, the ECB’s word was enough; for Target 2, the ECB actually helped pay off the obligations of distressed banks in the hope that these banks would eventually recover enough to repay the ECB.

The ECB's extended support of banking distress is unusual for a central bank. It raises important questions about what exactly the ECB does. It especially raises questions about the ECB's new role as a bank supervisor. Can the ECB be an effective supervisor while it has an incentive to practice forbearance?

Reflections

Starting in September 2007 from 5¼%, the U.S. Federal Reserve rapidly lowered its policy rate to a ¼ percent by late-2008. The U.S. Fed also initiated its first QE operations in December 2008.

Throughout, the ECB has been in a reactive mode: delays and half measures have been the norm. In 2007-8, it was obsessed with the threat of inflation, even though the rise in inflation was clearly temporary and the prospects for growth were evidently weakening. Only after the Lehman-induced meltdown in September 2008 did the ECB begin lowering rates. However, the response was always forced and the ECB obsession with inflation continued through mid-2011, when it twice raised interest rates. In October 2011, the ECB policy rate was still 1.5%, reaching a ¼% only in November 2013; and the debate on whether a seriously-sized QE is necessary is still ongoing.

Even the much-celebrated OMT decision came in the face of an imminent financial collapse. By then, the periphery was badly wounded, and the deep scars acquired then have remained. The ECB spent much of last year denying the risk of deflation. Finally, on June 5th this year it initiated actions that contemporary analysis warned would not be up to the task. And now the promise is to do more, but only if needed.

“Cheap talk” is a legitimate policy tool. With their words, policymakers, especially central bankers, can change expectations and create a self-reinforcing cycle of growth and optimism. But talk can also create a cognitive bubble.

The American philosopher and linguist George Lakoff explains that for those who live in a certain cognitive frame, the metaphors and rhetoric come to have real meaning and debating the details become the source of endless fascination. Mr. Draghi has successfully placed the current focus on the “if needed” metaphor. The ECB’s chief economist, in his November 18th interview with the Financial Times, repeated that the central bank remained “willing to act,” “if needed.” The consensus within the ECB’s Governing Council remains steadfast with a “wait and see” and “won’t rush” approach.

Others play by the rules of the cognitive frame. Thus, despite the serious concerns with the June 5th measures—documented carefully by my Bruegel colleagues—journalists have no interest in asking ECB officials: “What exactly are we waiting for?” The financial markets have no interest in public policy: once the rules are set, they seek opportunities for short-term bets. On July 9th, the International Monetary Fund’s Executive Board somewhat incredulously concluded: “Directors welcomed the exceptional measures recently taken by the European Central Bank (ECB) to address low inflation and strengthen demand, as well as its intention to use further unconventional instruments if necessary.” Belatedly, on November 25th, the OECD became a lone official voice calling for more urgent steps.

In the meanwhile, the futures markets are betting that euro area inflation in the coming year will be about 0.45% and over the next two years will be 0.55%. The continued risk of declining inflation is only partly due to global commodity price trends. The eurozone periphery’s debt-deflation cycle is set to continue, with spillovers through weak demand to the core and beyond that to the rest of the world.

Having delayed so long, if today the ECB were to buy sovereign bonds, as many think it should, the stimulative impact would be negligible

There is some risk that in this cognitive bubble the words create a deceptive sense of forward movement, breeding more inaction. Inaction causes the central bank to lose credibility since even apparently sensible actions lose traction (Bordo and Siklos, 2014). Having delayed so long, if today the ECB were to buy sovereign bonds, as many think it should, the stimulative impact would be negligible. The historically low sovereign yields will fall further: how will that help revive growth or inflation? A shift to a higher inflation target and one that is more “symmetric,” obliging the ECB to act more decisively, could help. But was a target needed to recognize that the euro area is falling into a debt-deflation cycle?

There are four possibilities. First, inflation may turn up, relieving the pressure on the ECB. In the current weak global economy, with China slowing noticeably, the probability of this happening is low. But the euro area may finally get lucky with a rebound in food and energy prices. Second, the ECB actions may have greater impact than the analysis in this blog gives it credit for. Third, the ECB could take truly bold action by coordinating with the US Federal Reserve and other central banks to engineer a substantial depreciation of the euro. And, in that fantasy land, there would also be a sizeable fiscal stimulus. Finally, of course, the drift could continue.

For their generous comments, and without implicating them, I thank Michael Bordo, Ajai Chopra, Guntram Wolff, and especially Giulio Mazzolini who produced the graphics despite the demands on his time before moving on.

References

Bordo, Michael and Pierre L. Siklos, 2014, “Central Bank Credibility: An Historical and Quantitative Exploration,” Presented at the 2014 Norges Bank Conference “Of the Uses of Central Banks: Lessons from History”, Oslo, Norway.

Hetzel, Robert, 2012, “The Great Recession: Market Failure or Policy Failure,” Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Hetzel, Robert, 2014, “Contractionary Monetary Policy Caused the Great Recession in the Eurozone: A New-Keynsian Perspective,” Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond, Working Paper WP 13-07R.

Read More: