Oil and the dollar will complicate the U.S. revival

At the start of 2015, two familiar features dominate the global economic outlook: continuing turbulence in financial markets and the relative strength

This article originally appeared in Bloomberg View

At the start of 2015, two familiar features dominate the global economic outlook: continuing turbulence in financial markets and the relative strength of the US recovery. One aspect of America's superior performance, though, has received surprisingly little attention, and that's the marked decline in the country's external deficit.

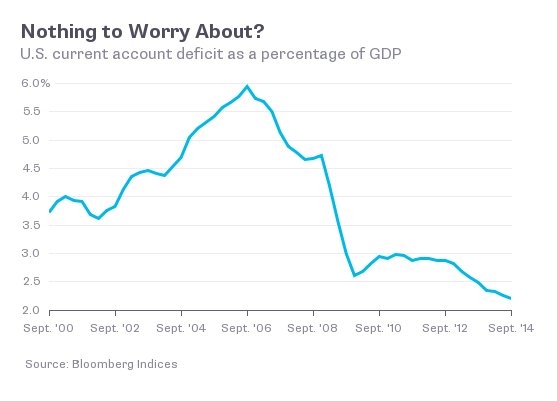

The shrinking of the current-account deficit -- from its peak of almost 6 percent of US gross domestic product in 2006 to 2.3 percent in 2013 -- ought to be a big story. Bear in mind, it happened even though the US has enjoyed stronger growth in domestic demand than either Europe or Japan, and despite the recent strength of the dollar. That took some doing.

In my early years of learning international economics, it was banged into my brain that the U.S. would always see its imports rise significantly when its domestic demand grew more strongly than that of other developed economies. Ten years ago many economists believed that the U.S. external deficit would persist until domestic demand gave way or the dollar collapsed (or both).

What concerns me as 2015 gets under way is that this little-noticed but highly significant adjustment could now be under threat.

One crucial variable is the price of oil. The US is a net oil importer, so the collapse in crude-oil prices has squeezed the current-account deficit. In the short term, it will continue to do so; in the longer term, however, other forces will come into play. Cheap oil will boost the real incomes of U.S. consumers, allowing them to spend more on imports. In addition, if the price of oil stays down, the recent surge of investment in the domestic production of shale oil and gas may stall or even go into reverse. The technological opportunity afforded by fracking -- and the prospect of a permanent improvement in the U.S. balance of trade in oil -- could be undone.

Another big factor is the aforementioned strength of the dollar. Over the past year, the dollar has appreciated against almost all the main currencies. Even if the connection isn't apparent yet, a stronger dollar will slow the decline of the US deficit.

On the one hand, if the dollar were to strengthen in 2015 as it did in 2014, there'd be a boost to consumer demand from higher real incomes, and this would support the recovery. On the other, the diminished competitiveness of U.S. producers in domestic and foreign markets would probably cancel out the benefit. Exports would fall and imports would rise. It's quite likely -- contrary to some short-term forecasts -- that the combination of cheap oil and a strong dollar will be more helpful to Japan and the euro area than to the United States.

If I were a U.S. policy-maker, I'd be concerned about this. If I were a governor of the Federal Reserve, I might be concerned enough to wonder whether the dollar's strength -- in effect, an unplanned tightening of U.S. monetary policy -- should make me want to postpone the first post-crash rise in short-term interest rates yet again.

True, a strong dollar will keep imported inflation in check --but inflation is not yet a concern. Meanwhile, further currency appreciation could do lasting structural harm to the economy by bringing the recent revival of US manufacturing to a premature halt. That's not all. Lately, unlike the other main currencies, China's renminbi has risen along with the dollar; at some point, policy-makers in Beijing are likely to act against the ongoing loss of competitiveness. That would add to the downside for the U.S. economy.

Many will say there's little the US can do about the fall in oil prices or the rise of the dollar -- and I expect they're right. Even so, I see US policy-makers mobilising their diplomats and hitting the phones, urging foreign counterparts not to solve their own economic problems at the expense of the US. Since 2008, the structure of the American economy has changed and, partly for that reason, the nation has recovered much of its strength. Those gains won't be surrendered lightly.