The below-zero lower bound

What’s at stake: The negative yields observed on some government and corporate bonds, as well as the recent move into further negative territory of mo

What’s at stake: The negative yields observed on some government and corporate bonds, as well as the recent move into further negative territory of monetary policy rates, are shaking our understanding of the ZLB constraint. This blogs review summarizes the recent debates on the binding nature of the zero lower bound. Next week, we’ll look at the implications of negative interest rates for financial stability.

Negative yields everywhere

Matthew Yglesias writes that something really weird is happening in Europe. Interest rates on a range of debt — mostly government bonds from countries like Denmark, Switzerland, and Germany but also corporate bonds from Nestlé and, briefly, Shell — have gone negative. And not just negative in fancy inflation-adjusted terms like US government debt. It’s just negative. As in you give the German government some euros, and over time the German government gives you back less money than you gave it.

Evan Soltas writes that economists had believed that it was effectively impossible for nominal interest rates to fall below zero. Hence the idea of the "zero lower bound." Well, so much for that theory. Interest rates are going negative all around the world. And not by small amounts, either. $1.9 trillion dollars of European debt now carries negative nominal yields, and the overnight interest rate in Swiss franc is around -1 percent annually.

Gavyn Davies writes that an unprecedented experiment in monetary policy is underway in two small countries in Europe. By pushing policy interest rates more deeply into negative territory than ever seen before, the Swiss and Danish central banks are testing where the effective lower bound on interest rates really lies. Denmark and Switzerland are clearly both special cases, because they have been subject to enormous upward pressure on their exchange rates. However, if they prove that central banks can force short term interest rates deep into negative territory, this would challenge the almost universal belief among economists that interest rates are subject to a ZLB.

Paper currency and the ZLB constraint

Miles Kimball writes that paper currency (and coins) guarantee a zero nominal rate of return, apart from storage costs, which are relatively small. It is then difficult for central banks to reduce their target interest rates below the rate of return on paper currency storage, which is not far below zero. This limitation on central bank target interest rates is called the “zero lower bound.” Because the zero lower bound is a consequence of how monetary systems handle paper currency, it is possible to eliminate the zero lower bound by alternative paper currency policies.

JP Koning writes that there are a number of carrying costs on cash holdings, including storage fees, insurance, handling, and transportation costs. This means that a central bank can safely reduce interest rates a few dozen basis points below zero before flight into cash begins. The lower bound isn't a zero bound, but a -0.5% bound (or thereabouts).

Gavyn Davies writes that in the past, economists have always assumed that the convenience yield on bank deposits is extremely small, so there would be a stampede into cash, led by the banks themselves, if the yield on deposits at the central bank went even slightly negative. But no one really knows whether that is true. In the long term, new businesses would appear, helping the private sector to handle and store cash cheaply and efficiently, but this may not happen quickly.

Reviewing the convenience yield on deposits and bonds

Evan Soltas writes that if people aren't converting deposits to currency, one explanation is that it's just expensive to carry or to store any significant amount of it. Therefore, the true lower bound is some negative number: zero minus the cost of currency storage. How much is that convenience worth? It seems like a hard question, but we have a decent proxy for that: credit card fees, counting both those to merchants and to cardholders. That's because the credit-card company is making exactly the same calculus as we are trying to make – how much can we charge before we make people indifferent between currency and credit cards? The data here suggest a conservative estimate is 2 percent annually.

Barclays (HT FT Alphaville) writes currency hidden under a mattress is useful for small transactions in your local market (the local café or store). However, it is of little use for large or distant transactions since armored trucks are neither cheap nor convenient. Internet transactions are an increasingly large share of both retail and business-to-business transactions, and bank transfers are an even larger share. Aside from the costs of transferring cash, both consumers and businesses derive utility from the convenience of book-entry (electronic) transactions.

Barclays writes that the value of that convenience likely forms the negative lower bound. Credit and debit card interchange fees, the fee card companies charge merchants for transactions, are a measure of how much that transaction utility is worth to both consumers and businesses that accept card payment. Until recent moves to regulate interchange fees, debit card interchange fees were approximately 1-3% of transaction value, depending on the card and the merchant. Credit cards, which remain unregulated, still command fees in that range. Coincidentally, the ECB has calculated that the social welfare value of transactions is 2.3%. If these rates represent an accurate measure of the value of transaction utility, they suggest that the negative lower bound for interest rates likely is considerably lower than the –75bp in Sweden and Switzerland.

Paul Krugman writes that the medium of exchange utility is irrelevant. In normal times, once interest rates on safe assets are zero or lower, liquidity has no opportunity cost; people will saturate themselves with it. That’s why we call it a liquidity trap! And what this means is that the marginal dollar of money holdings is being held solely as a store of value — the medium of exchange utility is irrelevant. Paul Krugman writes that when central banks push interest rates on government debt below zero, the effective lower bound is the return on cash held by people who would otherwise be holding that government debt — not people looking to expand their checking accounts. So the liquidity advantages of bank deposits over cash in a vault are pretty much irrelevant. It’s all about the cost of storage.

JP Koning writes that Krugman is assuming that liquidity is a homogeneous good. It could very well be that "different goods are differently liquid," as Steve Roth once eloquently said. The idea here is that the sort of conveniences provided by central bank reserves are different from those provided by other liquid fixed income products like deposits, notes, and Nestle bonds. If so, then investors can be saturated with the sort of liquidity services provided by reserves (as they are now), but not saturated by the particular liquidity services provided by Nestle bonds and other fixed income products. Assuming that Nestle bonds are differently liquid than central bank francs, say because they play a special roll as collateral, then Soltas isn't out of line. Once investors have reached the saturation point in terms of central bank deposits, the effective lower bound to the Nestle bond isn't just a function of the cost of storing Swiss paper money, but also its unique conveniences. Koning quotes Michael Woodford’s Jackson Hole paper: “one might suppose that Treasuries supply a convenience yield of a different sort than is provided by bank reserves, so that the fact that the liquidity premium for bank reserves has fallen to zero would not necessarily imply that there could not still be a positive safety premium for Treasuries”.

A bit of history of thought on negative interest rates

Brad Delong writes that the idea of making money earn a negative return is not entirely new. In the late 19th century, the German economist Silvio Gesell argued for a tax on holding money. He was concerned that during times of financial stress, people hoard money rather than lend it.

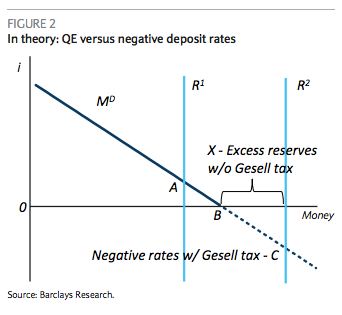

David Kehoane writes that for those not familiar with the 19th century idea of a Gesell tax, it’s basically a stamp tax on money that acts as a negative interest rate. The idea being that in order to be legal tender notes would have to bear an annual/ monthly stamp provided by the government — and for which the government would charge a fee.

Brad Delong writes that this is not an obscure idea. Silvio Gesell is the topic of part VI of chapter 23 of Keynes’s flagship work, The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money. And it’s not just Keynes in his flagship work. There are 55,000 google hits for “Silvio Gesell.” Patinkin (1993) reports that Irving Fisher advocated Gesell-based “velocity control” in his 1932 Booms and Depressions. Nobel prize-winning Maurice Allais was an advocate as well. Gerardo della Paolera and Alan Taylor are Gesell’s biggest boosters today in their book Straining at the Anchor: The Argentine Currency Board and the Search for Macroeconomic Stability, 1880-1935, a University of Chicago Press book that is part of the NBER’s series on “long term factors in economic development.” Willem H. Buiter and Nikolaos Panigirtzoglou writing in the Economic Journal in 2003: “Overcoming the Zero Bound on Nominal Interest Rates with Negative Interest on Currency: Gesell’s Solution.”

JP Koning writes that a central banker can safely guides rates to a much more negative rate than before, say to -2.5% rather than just -0.5%, by varying the conversion rate between low denomination notes/electronic currency and large denomination notes. Central banks currently allow free conversion between deposits, low value notes, and high value denominations. The idea here is to keep the conversion window open, but levy a fee, say three cents on the dollar, on anyone who wants to convert either deposits or low denomination notes into high denomination notes. Conversion between low value notes and deposits remains free of charge. This method is akin to Miles Kimball's crawling peg, except that the conversion penalty is set on high denomination notes only, not cash in general.