Now you see it, now you don’t

The first Italian case of bail-in.

On the 17th July, the Italian authorities began the liquidation of Banca Romagna Cooperativa (BRC), a small Italian mutual bank that had been in trouble since 2013. In the BRC resolution process, equity and junior debt have been bailed in. The case has passed largely unnoticed abroad, but this is effectively the first instance of a bail-in in Italy.

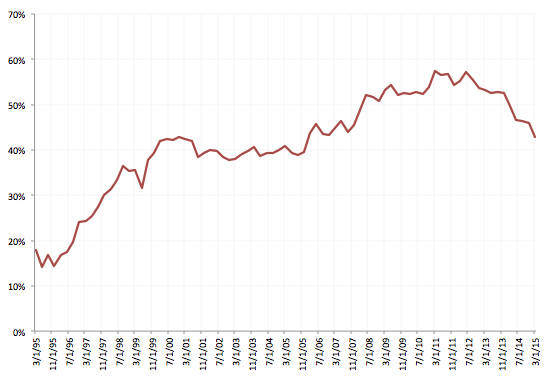

Percentage of bank bonds in total bond portfolios of Italian Households

The need to carry out a preliminary bail in in bank resolution cases was established in the amended state aid rules, which constitute the transition framework to the new recovery and resolution regime that will be in force from 2016. The amended state aid framework prescribes that a bail in of junior debt must be carried out before any public money can be injected into the bank.Source: elaboration based on data from Central Bank of Italy

The rules will be toughened starting in January 2016, when the bail-in tool foreseen under the Bank Recovery and Resolution Directive (BRRD) will become operative. The spirit of this provision is to ensure that the private sector bears a share in the recapitalisation, restructuring or resolution of troubled banks and to avoid the burden being entirely shifted onto the public sector balance sheet, thus reinforcing the sovereign-banking vicious cycle that the creation of Banking Union is supposed to counteract.

In a press release assessing the case, Fitch Ratings said that the initial plan in the Italian case was to use funds from Italy's Deposit Guarantee Insurance Fund to make up for the capital shortfall. But under the amended state aid, a preliminary bail-in of junior debt is mandatory. Therefore, junior bondholders have been bailed in. And yet they haven’t.

Despite the bail-in, in fact, no loss was suffered by retail bondholders as the Italian mutual sector's Institutional Guarantee Fund decided to reimburse them in full to “preserve the reputation of the sector”. The Institutional Guarantee Fund is technically not public money (it’s financed contributions from banks) but this still looks like a circuitous way to do what was initially planned, i.e. to avoid placing losses on private creditors. A few months ago a similar case (Carife - Cassa di Risparmio di Ferrara) also resulted in a "creative" solution being proposed, with the Italian deposit guarantee scheme Fondo interbancario di tutela dei depositi (FITD) possibly bailing out the bank and becoming the sole shareholder with the intention to sell it in the future.

The reason behind this is that all junior debt in BRC was actually held by retail depositors. This is by no means exclusive to BRC, but it points to a broader issue that could raise problems in the future. Households in Italy are relatively exposed to bank debt, which accounted for over 40% of the total bond assets held by households in the first quarter of 2015 (down from a peak of almost 60% in 2011/12).

According to Fitch, the BRC case highlights generally“poor conduct by Italian banks in raising subordinated and hybrid debt through their retail branches”. The Bank of Italy recently warned about the risks of institutions placing their own debt to retail buyers under the changed resolution landscape.

Italy is among the countries that failed to comply with the January 2015 deadline for implementing the BRRD into national law, but its transposition will limit the degrees of freedom over “creative” solutions like BRC and CARIFE. This may turn out to be a non-negligible problem for those smaller Italian banks that have relied heavily on retail customers to invest in less secure funding instruments.