The then and now of tightening cycles

What’s at stake: This week the Fed will be considering whether to raise its interest rate for the first time in nearly a decade. In a volatile context

The significance of the initial rate hike

Eric S. Rosengren writes that macroeconomic models of the economy overwhelmingly suggest little impact on the broader economic landscape from moving the timing of initial interest rate hikes forward or backward by a couple of months. However, the future trajectory of interest rate increases – that is, whether increases to more normalized levels occur quickly or more gradually – is, by contrast, likely to have a meaningful impact on employment and inflation.

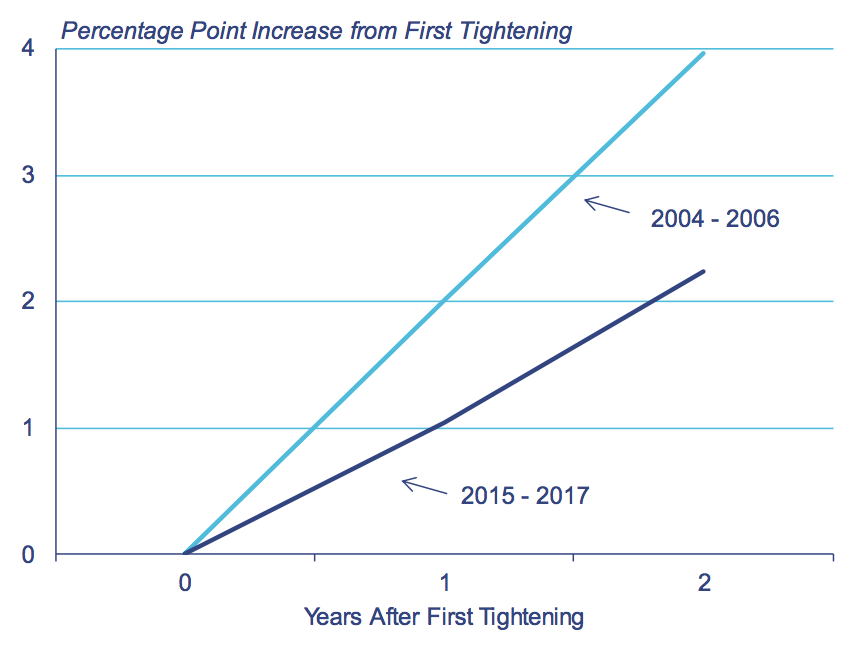

Martin Wolf writes that any increase would be significant: first, it would indicate the Fed’s belief that the policy can be “normalized” after almost seven years of post-crisis healing; second, it would indicate the beginning of a tightening cycle. One of the reasons for believing the latter is that this is how the Fed has historically behaved: the last such cycle began with rates at 1 per cent in June 2004 and ended with rates at 5.25 per cent two years later. Without doubt, beginning a tightening cycle for the first time in more than 11 years would be a significant moment. It would also signal more than an immediate rise in rates. Lawrence Summers agree and write that arguments of the “one and done” variety or arguments that the Fed can safely raise rates by 25 BP as long as it’s clear that there is no commitment to a series of hikes are specious.

A quick history of tightening episodes

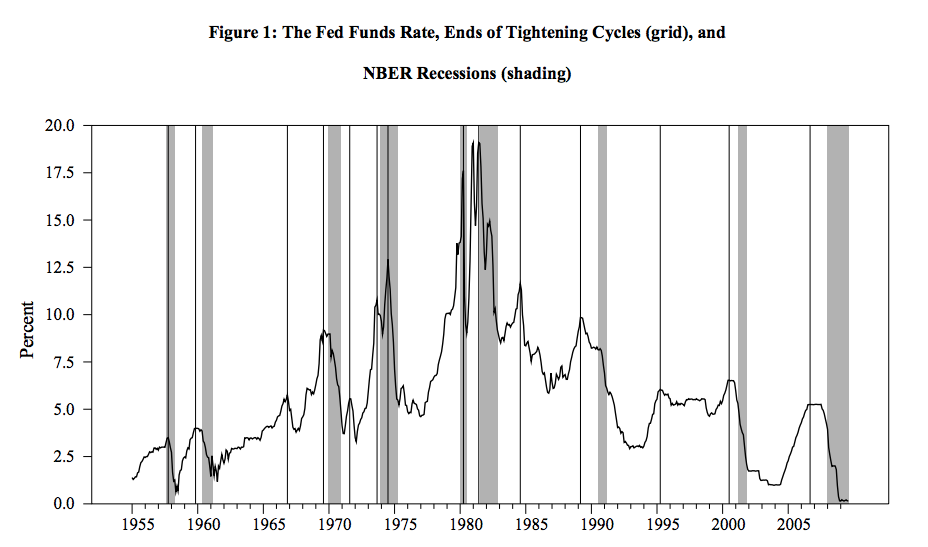

The Economist writes that there have been 12 American tightening cycles since 1955, and they have lasted just under two years on average. In five of the past seven instances, however, the Fed has relented in a year or less. The inflationary periods of the 1970s and early 1980s saw the biggest increases in interest rates; that helped push the mean increase over the 12 cycles to five percentage points. But the median change may be a better guide to the coming cycle; it stands at just over three percentage points.

Source: NY Fed

Tracy Manzi writes that rate increases have historically led to greater equity market volatility, but they have rarely signaled the end of a bull market. The stock market continued to rise in the last five tightening cycles. Most bear markets in bonds have occurred during Fed rate hike cycles. The 2004 tightening cycle was a rare exception. In 2004, long-term interest rates remained remarkably stable, trading in a very narrow range, despite the Federal Reserve’s interest rate hikes from a low of 1.0% to 4.25%. In most instances, long-term interest rates should rise when policy makers increase short-term interest rates.

The 1994 episode

Martin Hochstein writes that the 1994 episode is a good example of what could go awry from a financial markets perspective when central banks start to tighten monetary policy. Though in early 1994 Chairman Greenspan had already been hinting at potential rate hikes for some time, the timing and magnitude of the subsequent monetary tightening came as a major surprise to analysts. Obviously this surprise spilled over into the financial markets. Over the course of the cycle almost all asset classes suffered losses, with global and Emerging Market equities hit the hardest. But US equities lost ground as well, temporarily losing almost 10 % before finishing the cycle at minus 2 %.

The Economist writes that 1994 is also a pertinent example because the Fed had kept rates low for a long time in order to help the financial sector, which was still recovering from the savings-and-loan crisis of the late 1980s. When it finally did begin to raise rates, the pace of tightening seemed to catch many investors by surprise, particularly those investing in mortgage-backed bonds.

This time is different

Martin Wolf writes that the likely destination and speed of travel are enigmas because the US economy is not behaving normally. After nearly seven years of zero interest rates, the inflation of which critics warned is invisible. This is not normal. Lawrence Summers writes that, if rates were now 4 per cent, there wouldn’t be much pressure to raise them. That pressure comes from a sense that the economy has substantially normalized during six years of recovery, and so the extraordinary stimulus of zero interest rates should be withdrawn.

Source: Boston Fed

Eric S. Rosengren writes that there are very good reasons to expect a much more gradual normalization process than occurred in the previous two tightening cycles. Importantly, this is not just my view; the Summary of Economic Projections – the “SEP” – released after the June FOMC meeting, which incorporates the federal funds rate expectations for all the FOMC participants assuming appropriate monetary policy, indicates that Federal Reserve policymakers expect a gradual tightening cycle. The implied path of the SEP is much slower than the path taken in 2004, with the federal funds rate increasing at roughly half the pace of that tightening episode. This significantly slower pace reflects that lingering headwinds resonating from the financial crisis, and continued low inflation rates both here and abroad, likely require a different path of tightening.