No coordination without representation

Further democratic legitimacy is a pre-requisite to economic union. This article explores how economic policies in the euro area should be coordinated

Over the past weeks, EU finance ministers and institutions have been keeping their powder dry for what was set to become only the latest chapter of the controversy between the champions of a “rule-based” approach to European governance and those in favour of discretion and flexibility. On October 6, the ECOFIN discussed how flexibility should be applied when implementing the Stability and Growth Pact; a topic on which the Commission issued a contentious communication in January 2015.

The argument of those banging their fists on the table was that excessive fiscal flexibility is being granted to countries on the basis of dubious or partial structural reform efforts. These claims have a certain degree of legitimacy and expose deeper problems that will irremediably come to the fore when, as part of the longer-term strategy detailed in the Five Presidents’ Report, discussions will start on how to set up an economic union (or structural reform coordination framework).

Rationale for an economic union

A cogent economic argument in favour of setting up a “euro area governance of structural reforms” was expressed by Mario Draghi in Sintra earlier this year. In that occasion, the ECB president explained how, on top of boosting productivity and long-term growth, structural reforms are expected to make an economy more resilient to shocks by facilitating a speedy reallocation of resources. Within a monetary union, resilience to (asymmetric) shocks is however a public good (especially in the absence of large scale fiscal transfers) and hence “a legitimate interest of the whole union”. Ignoring this aspect, Draghi concluded, could lead to permanent economic divergences and ultimately represent a threat to the integrity of the euro area.

The concept that in order to be sustainable in the long term the European monetary union should be complemented by an economic-, on top of a fiscal, and financial market union (together with some degree of enhanced democratic legitimisation) is not all that new but actually dates back to late 2012 (Van Rompuy et al, 2012).

However, as evidenced by an index of institutional integration I developed together with former ECB colleagues (Dorrucci et al, 2015), crisis management over the past 5 years focussed on strengthening the fiscal framework and setting up a banking union, with very little progress made in achieving an economic union. As such, the latter remains the least integrated pillar of EMU.

Figure 1. Progress made under various headings according to the Index of European institutional integration (EURII)

Note: For more information on definitions and methodology, please refer to the original ECB Occasional paper 160.

Source: Dorrucci et al. (2015)

Why is economic union different?

One of the reasons for the very limited progress made on the economic union front is that, conversely from a fiscal framework[1], it is much harder even just to start envisioning a feasible rules-based system to coordinate structural reform. Rather, a functioning economic union would need to be steered by a European institution with large discretionary powers. This, in turn, calls for a very strong democratic legitimisation and accountability at European, rather than national, level.

Underlying this trenchant assessment are three key elements:

- Structural reforms cannot be objectively measured

It is not by chance that every serious report or speech on structural reforms starts with a definition of what the author or speaker means by “structural reforms”. This is because there is no widely-accepted, comprehensive, and precise definition of which government policies classify as structural reforms[1]. More importantly, as structural reforms can be as diverse as ranging from an overhaul of the judicial system to a change in the unemployment benefits system, there is no real way to aggregate them and produce an unequivocal comprehensive reform effort indicator, around which rules could be drawn.

International financial institutions such as the IMF have had to deal with this sort of issues for decades now, as conditional lending requires a tracking of policy implementation in programme countries. Interestingly, for what concerns structural reforms[2], the IMF has never developed a single quantitative indicator that objectively determines whether a loan tranche should be paid or not, but rather rests of the expert judgment of its country teams and on the political judgment of its Executive Board[3]. Notwithstanding the IMF’s apt emphasis on equal treatment of countries, its own decision-making system is effectively characterised by discretion.

Somewhat surprisingly given its decade-long experience in programme countries, the IMF has recently been pushing for a rule-based coordination of reforms in the euro area (Banerji et al, 2015). The proposed system should “reduce the European Commission’s ability to exercise excessive discretion in utilising its enforcement tools”, and rather be based on “semi-automatic sanctions”. The lack of appropriate reform benchmarks is considered a mere “technical hurdle” that can be overcome with “prior collective agreement on the methodology”.

However, past euro area governance experiences show that the arbitrary nature of complex and non-unanimously accepted methodologies exposes them to criticism as soon as they require corrective measures from a (large) country[4].

- Structural reform impact cannot be objectively measured

The fact that structural reforms cannot be quantitatively measured and aggregated (see point 1) would not be a problem if their impact could. By definition, all structural reforms aim at boosting medium-/long-term growth. Hence, as somewhat suggested by Banerji et al (2015), reform progress could be individually measured based on its outcome and, ultimately, aggregated based on its (forecast) impact on GDP.

Once again, however, the problem arises that there is no precise and widely-accepted methodology to measure reform impact, neither ex ante nor ex post. Large-scale DSGE models can be used to estimate the impact of reforms on GDP but the reality is that these estimates rely heavily on the set of original assumptions made[5].

There are three direct implications originating from this shortcoming:

- reforms priorities cannot be objectively determined based on the ranking of their impact on output, but will rather have to remain subject to political judgment (either at national or European level);

- national reform efforts cannot be mechanically compensated with direct financial transfers[6] from the EU;

- spillovers to the rest of the euro area originating from a reform in one country cannot reliably be quantified, meaning economic rules can hardly determine which policies should be coordinated and which can remain fully national.

- Agreement on the intents, disagreement on the means

Aside from the methodological difficulties of coming to grips with structural reform coordination, a final obstacle that gets in the way of a rule-based economic union is the fact that there is no unique policy mix toward which European countries should evidently strive.

Although all governments would agree on some general principles like the importance of having a high-quality educational system, of safeguarding property rights, of having an efficient public administration and welfare system, and so on, there are very few fields where these translate into a unique policy mix on which all countries would concur.

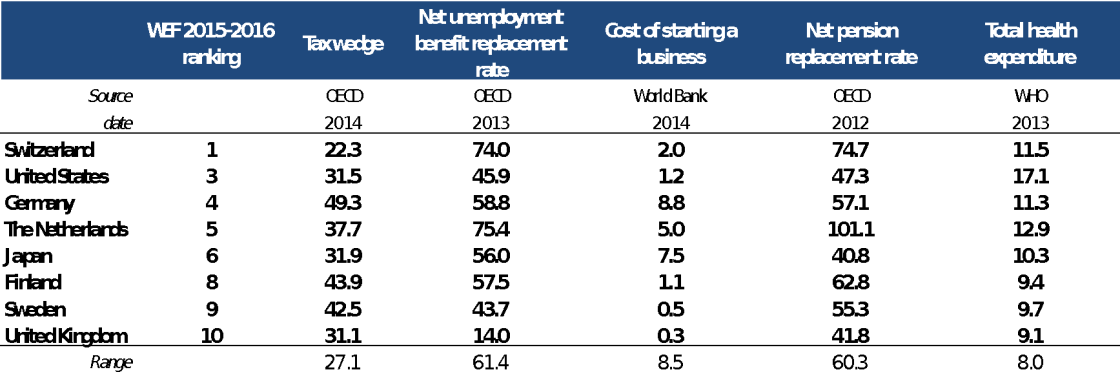

Table 1 below takes the OECD countries that ranked among the top 10 in the latest issue of the World Economic Forum’s Global Competitiveness Indicator, and for each of them displays their economic policy stance on some of the indicators that Banerji et al (2015) have recently suggested as potential candidates for benchmarking reform progress.

Table 1. Economic policy stance indicators for the top-performing OECD countries in the WEF global competitiveness ranking

Note: Average tax wedge for a single person at average earnings, no child; Net benefit replacement rate for initial phase of unemployment and a single person at average earnings, no child and no social assistance "top-ups" or cash housing benefits available in either the in-work or out-of-work situation; Cost of starting a business expressed as a percentage of average GNI per capita; Net pensions replacement rate for men, % of pre-retirement income; Total health expenditure as a % of GDP.

Source: OECD, World Bank, WHO

The most competitive countries in the world display tax wedges that range from 22.3% to 49.3%, have net unemployment benefit replacement rates between 14% and 75.4% of pre-unemployment income, costs of setting up a business between 0.3% and 8.8% of GNI per capita, and so on.

All this to say that it is hard to imagine how even a political body as the Eurogroup – whose members however respond to national, rather than European, incentives and accountability – could come to an agreement on standard benchmarks towards which all governments should aim their reform efforts. Countries enjoying reasonable macroeconomic conditions will refuse the claim that their competitiveness model should be changed towards the EU/OECD average or best practice[8].

Conclusions

This brief article aimed to illustrate how economic policies in the euro area should indeed be coordinated, but this cannot be done in a mechanical rules-based manner. Arguing the contrary suggests a cavalier understanding of the complexity of economic policymaking.

The current Macroeconomic Imbalance Procedure represents a useful mechanism for the loose coordination of reforms in Europe, functioning as an early-warning system for imbalances, and providing an important forum of discussion on national reforms and best practices. However, the key problem with the system is that its main discretionary decision-making body – the Council – is an institution whose members respond to national re-election incentives and accountability, rather than representing Europe as a whole[9]. Within this setting, simply making the Country Specific Recommendations legally binding, and hence reducing the scope for national discretion, would not make for a successful economic union.

On the other hand, an effective governance of structural reforms can only be organised around a truly European institution, which will need to set economic priorities (in a discretionary way) and evaluate reform progress (in a discretionary way). Given the decisions it will have to take, and the mistakes that will inevitably be made in the process, this institution will need a higher degree of democratic legitimacy and accountability than even the Commission currently enjoys.

Ignoring these facts and simply progressively curtailing national sovereignty over structural reforms without establishing a democratically accountable federal institution to steer the process will only exacerbate animosity among member states and might end up endangering the very same integrity of the euro that economic union was supposed to safeguard.

[1] Aside from the idiosyncrasies of the European fiscal framework, several fiscal rules have been successfully set up around the world at both national and regional level. For a thorough review, please refer to Hallerberg et al (2009).

[2] In the aforementioned speech, Draghi defines structural reforms as “measures permanently and positively altering the supply side of the economy”. Although passing the first two tests, this definition can hardly be considered precise and could potentially encompass almost any government policy.

[3] Structural benchmarks, in IMF jargon.

[4] Ivanova et al (2003) of the IMF develop a quantitative indicator of structural conditionality implementation based on the IMF MONA database. By own admission of the authors, this index can at best be considered a proxy of implementation given the wide range of caveats involved and, to my knowledge, is not used by the IMF Executive Board to take policy decisions.

[5] In October 2014, Italy, who was very close to falling into the corrective arm of the SGP, questioned the way in which the European Commission computed potential output: “the decline in potential GDP growth rate stemming from the model agreed under the EU is particularly marked in Italy […] The prediction of the potential output made by the model must therefore be considered with extreme caution.” (MEF, 2014)

[6] This peculiarity does not apply to fiscal policy, where the budgetary impact of individual fiscal measures can be estimated quite precisely ex ante and becomes known ex post.

[7] In EU jargon, the concept is known as “reform contracts”.

[8] Somehwat different is the situation of countries that are in deep economic crisis and whose growth model is then prima facie dysfunctional. This is the case for countries entering an ESM programme. However, a functioning economic union should foster reforms in normal times in order to reduce the likelihood of having to resort to the euro area crisis management mechanisms (ESM and OMT).

[9] The limits of the current system have become evident throughout the Greek bailout saga, where some Eurogroup members took positions dictated by their national electoral calendar and dynamics, rather than in the interest of Europeans (and hence also Greeks) as a whole, as discussed inter alia by Bastasin (2015).