Are regional governments causing deficit overshooting in Spain?

Spain once again missed its deficit target in 2015 and it seems unlikely that 2016 will be any better. The central government has pointed to regional

Spain is again in the spotlight due to having missed its deficit target under the Stability and Growth Pact (SGP). It is not the first time Spain has missed the target. In 2009, the Council of the European Union concluded that an excessive deficit existed in Spain and requested the country to end it by 2013.

In 2013 Spain received an extension, giving it until 2016 to correct its excessive deficit. The European Commission argued that ‘effective action’ (i.e. expenditure cuts, tax increases and structural reforms) had been taken, but that ‘adverse economic events’ had prevented the economy adjusting within the agreed timing.

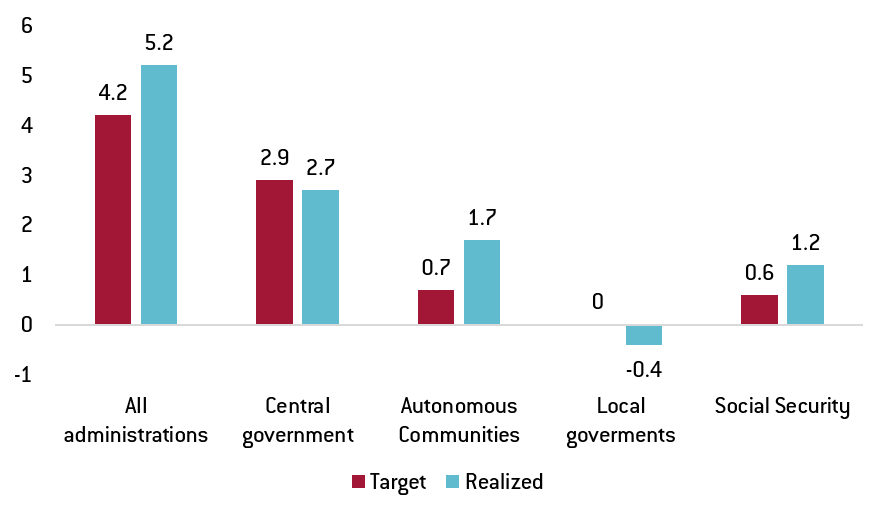

The targets set in 2013 for the deficits in 2014 and 2015 were 5.8 and 4.2 percent of GDP respectively. Although in 2014 the deficit target was reached, Spain recorded a deficit of 5.2 percent of its GDP in 2015, 1 percent above the target set by the Council (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Fiscal deficit as a share of GDP in 2015, broken down by administrative level

Note: ‘Autonomous communities’ represents the Spanish regions

Source: Eurostat and Spanish Ministry of Finance

This time it looks like the European Commission has run out of patience. On the 9 of March 2016, it released an ‘Autonomous Commission Recommendation’. This consists of an early alert to ensure timely correction of excessive deficits, a tool which was introduced in the ‘Two-Pack’. This instrument had only been used twice before, for France and Slovenia in 2014.

Two main reasons for non-compliance with the deficit target are highlighted in the document:

- First, the fiscal reform that the central government implemented in 2015 reduced personal income taxes.

- Second, while regional deficits increased more than expected in 2015, the Spanish government did nothing to stop this, despite having political instruments at hand (the budgetary stability law allows for coercive measures if deficit targets are not reached, such as withholding credit provided by the state).

Indeed, Figure 1 shows that while the central government met its fiscal target and local governments even had a surplus of 0.4%, the regional deficit exceeded its target by 1% of Spanish GDP and the social security fund deficit (managed at a central level) was 0.6% higher than the objective.

Spain is currently in an extremely delicate political situation, with new elections on the horizon. Therefore, it is unlikely that Spain will manage to fulfil the 2.8% fiscal deficit objective set for 2016. Anticipating this, Prime Minister Mariano Rajoy is negotiating a relaxation of the target with the European Commission (from 2.8% up to 3.7%).

The central government has taken distinct measures to contain regional budget deficits. For instance, the Spanish Minister of Finance and Public Administration, Cristóbal Montoro, has sent letters to the different Autonomous Communities (Spanish regions) which have exceeded their deficit objectives (14 of out 17, not including the two autonomous cities, Ceuta and Melilla), warning them to adjust their public finances. Moreover, two Spanish regions (Extremadura and Aragón) have seen some of their funds seized for paying their suppliers too late. Finally, Montoro held a meeting last week with his regional counterparts to make sure that regional spending does not increase during 2016.

The regional Finance Ministers’ reactions did not take long. Their claims can be summarized in two main arguments.

- Spanish regions are under-financed. The common argument used for sustaining this hypothesis is that while the regions have acquired important duties over the last two decades on the expenditure side, such as provision of public services (education and healthcare), they have not obtained corresponding rights on the revenue side.

- Regional deficit targets are too strict. Regional public spending is around one-third of total public spending, as ‘El País’ points out. Consequently, regional politicians argue that while central government allows itself to have a loose deficit target, it shifts fiscal consolidation to the regional level by imposing too strict fiscal targets.

Whatever the causes of the excess deficit in 2015, Spain may face negative consequences. If Spain does not comply with SGP rules, it could face a fine of 0.2% of its GDP (around 2 billion euros). Although this measure seems unlikely, the Council fined Spain with 19 million euros last year for manipulating statistics, based on a proposal by the European Commission. The reason was that a fraction of healthcare expenditure in one of the Autonomous Communities was hidden with the aim of disguising its deficit figures.