Japan needs labour market reform, not just higher wages

The Japanese government is trying to boost wages, but this is not enough to jumpstart growth. Japan needs to reform its labour market to increase the

Japan is once again defying common economic sense. While its unemployment rate is at the lowest level in almost two decades, wage growth has been disappointing, and the government is even putting pressure on companies to increase wages.

The ongoing wage negotiations for the next fiscal year are increasingly relevant for the success of Abenomics, Prime Minister Abe’s growth programme. Expectations of wage increases have been rather low so far, which is disappointing for the Bank of Japan (BoJ), which focuses on wage negotiations to help it achieve its inflation target. This may be the objective of the BoJ, but it is not the ultimate objective of Abenomics, which is to jumpstart growth in Japan.

Even just to achieve the BoJ’s objective of raising inflation, all sectors in the Japanese economy would need to feel pressured to increase prices. But at the moment the government is barely managing to force wage increases in large corporations, and certainly not in the rest.

In fact it is the companies less willing to raise wages, which are usually smaller companies, who are creating the bulk of the new jobs. This is because of decreasing labour productivity in the Japanese economy, especially in the sectors like healthcare and restaurants, where most of the new jobs are being created.

Such big differences in labour productivity make it difficult to increase inflation, but the aggregate fall in labour productivity also makes it extremely difficult for Japan to raise potential growth and for Abenomics to succeed. Japan needs to make labour market reform the heart of its reform programme. This means that the third arrow in Abenomics should be centered on a massive labour market reform.

Resilient labour market

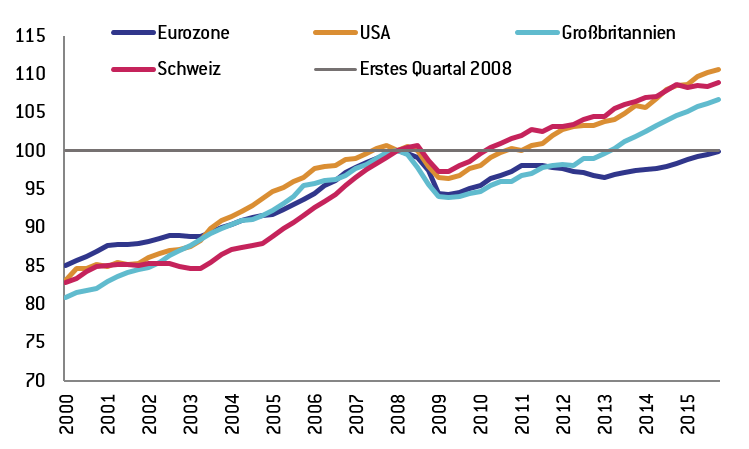

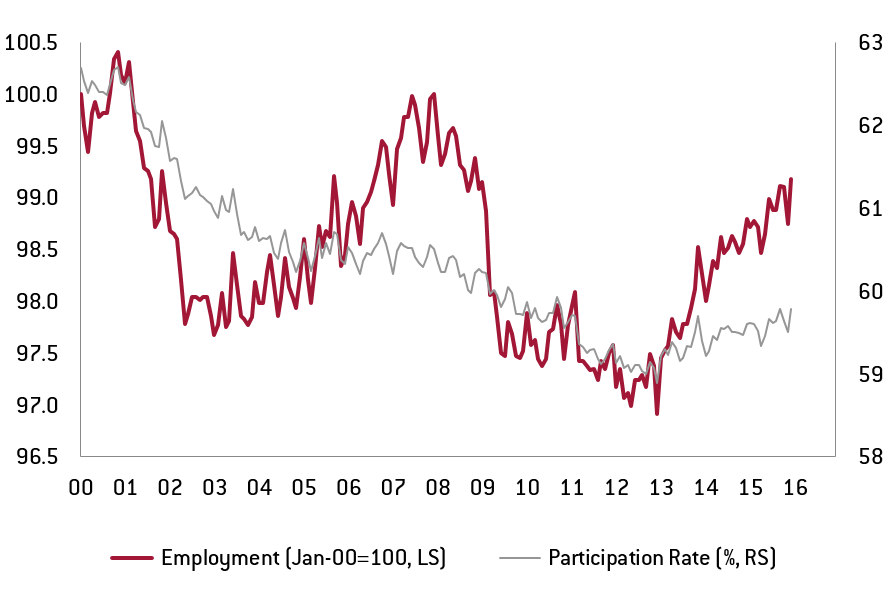

Since the global financial crisis in 2008-09, Japan’s unemployment rate has fallen from 5.5% in June 2009 to 3.2% in January 2016, the lowest level in almost two decades (Chart 1). To add to the good news, employment has steadily increased, with a higher participation rate (Chart 2).

At the same time, companies are suffering from the largest employment shortage since the early 90s, according to the Mach Tankan survey. In principle this should give workers bargaining power to demand higher wages, but this is not really happening. In turn, the corporate profit rate continued to be high, about 14% according to recent data, and close to the highest level since the Tankan survey began in 1985.

Chart 1 - Japan: Labour market

Sources : Datastream, NATIXIS

Chart 2 - Japan: Employment & participation rate

Sources : Datastream, NATIXIS

Disappointing wage growth

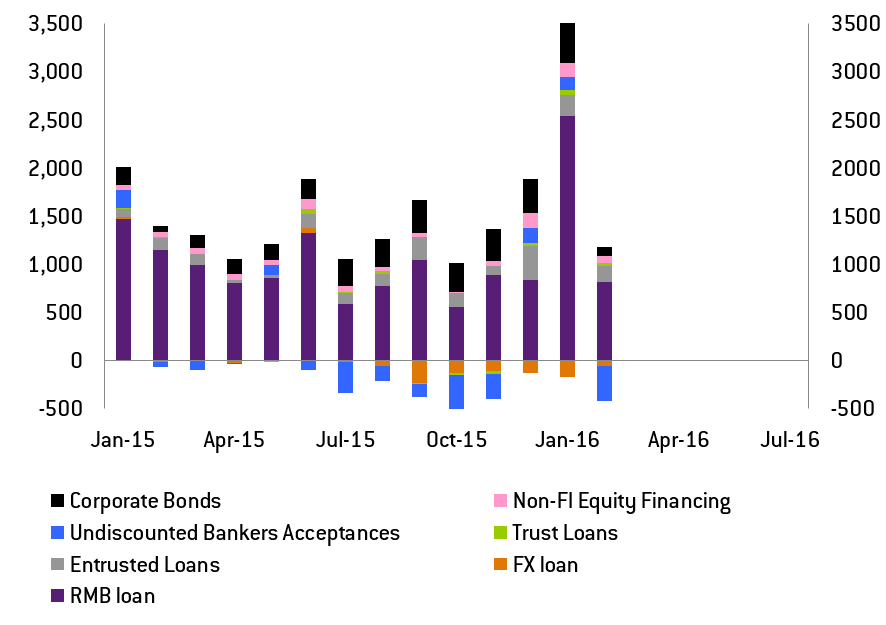

In spring 2015 the Japanese government, as well as the BoJ, were already openly supporting wage hikes during wage negotiations for the 2015 fiscal year (2015FY). Senior government officials visited large Japanese companies to “explain” Abenomics. In reality, companies were pressured to lift wages, so that the government could achieve its goals. BoJ Governor Kuroda put great emphasis on the importance of wage increases, both to boost inflation and to increase private consumption to further contribute to economic growth.

This also reflects the BoJ‘s intention not to meet the inflation target through a weaker yen and its impact on import prices, as this would have weakened Japanese consumers’ purchasing power and therefore their private consumption. After all of the government pressure, the spring wage negotiation in early 2015 for FY15 was considered successful, with the largest wage increase in seventeen years agreed (Chart 3).

Chart 3 - Japan: Spring wage negotiation

Sources : Datastream, NATIXIS

The initial “success” did not last long, and overall wage growth during FY2015 has been rather disappointing. Nominal wage growth has been limited to about +0.3% so far, which is very low at a time of high employment. A comparable year in terms of unemployment was the fiscal year of 1996 (FY96), where wage growth was much higher (+1.2% YoY).

A simple extrapolation, based on the philipps curve, suggests that wages would have grown close to +1.2% in FY15 if the structure of the Japanese economy had remained the same. However, Japan has gone through major structural shifts in the past two decades. In particular, productivity gains have slowed, contributing to disappointingly low wage growth.

Slowing labour productivity

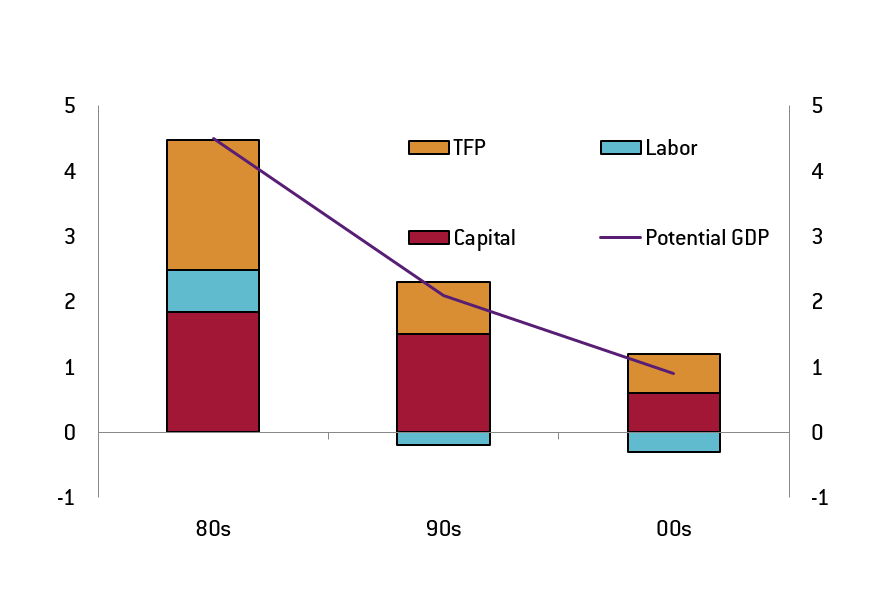

Labour productivity growth has steadily slowed over the past few decades (Chart 4). While it grew about 3% in the 80s, it softened to around 1% in the early 90s and even fell by -0.7% in 2014. With wages following labour productivity, stagnation in labour income is a natural economic consequence of this process.

Chart 4 - Japan: Labour productivity

Sources : Datastream, NATIXIS

The macro view

From a macroeconomic perspective, lagging capital accumulation and decreasing total factor productivity (TFP) are the main reasons for the stagnation in labour productivity.

Capital accumulation has fallen since the asset price bubble burst in the early 90s. Supported by optimism in the 80s, business investment significantly outpaced the depreciation of the capital stock, resulting in rapid capital accumulation. However, once the bubble burst in 1991, Japanese companies were preoccupied with restructuring their balance sheets and deleveraging. This is why depreciation of the capital stock largely exceeded investment during this deflationary period.

Given the BoJ’s slow reaction to deflation, high real interest rates not only discouraged business investments but also caused the yen to appreciate. This appreciation was behind the hollowing out of the economy, and the transfer of production by Japanese corporations overseas. Even after the launch of Abenomics, and, its first “arrow”, with enormous quantitative easing by the BoJ and increasingly low real interest rates, capital accumulation has been very small. Insufficient improvement of the capital stock is one of the reasons for Japan’s lower productivity.

As for TFP, which measures how efficiently production is carried out after skills, labour and capital are put into the process, there are many reasons for its fall (Chart 5). Firstly, the hollowing out of the economy reduced the share of the most productive sector, manufacturing, while increasing the share of the service sector in the Japanese economy. The service sector is dominated by SMEs, which are particularly behind in IT investment.

This might be due to Japan’s generally high level of job security, which has made companies reluctant to introduce IT to replace the unskilled labour force. During the prolonged deflationary period, they may not even have had adequate financial resources to invest in IT.

Chart 5 - Japan: Potential growth rate (%)

Source: Cabinet Office

The share of part-time workers has continued to increase over the past few decades due to the increasing role of the service sector. This has helped companies reduce costs, especially training costs, which made sense for firms when the economy was going through a recession. However, for the economy as a whole, firms’ decisions collectively reduced the skill of the labour force, lowering Japan’s labour productivity so much that it became negative in the 1990s and even more negative in the 2000s.

The micro angle: The situation sector-by-sector

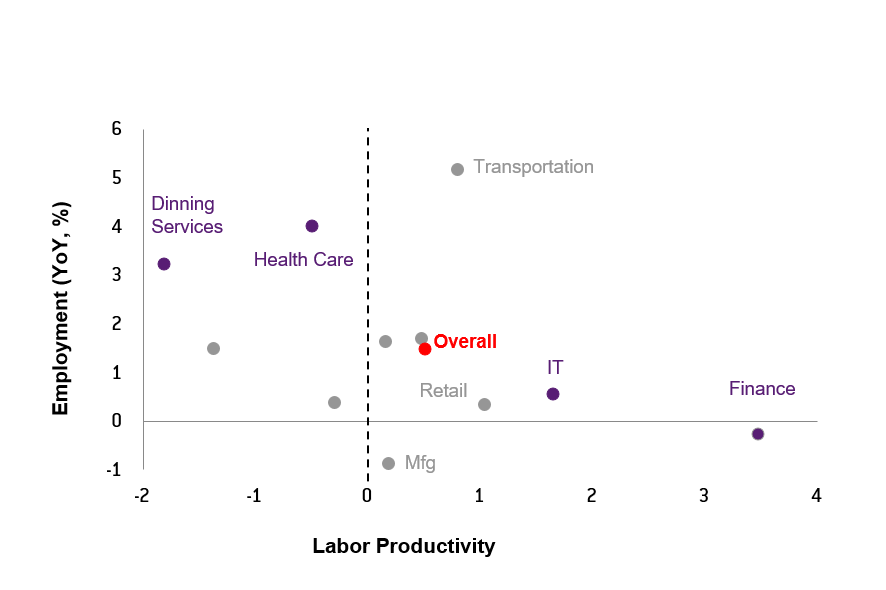

Sectors with the highest productivity are generally not creating jobs, while those with the lowest productivity are, pushing down labour productivity for the economy as a whole. In particular, sectors with high productivity such as finance and IT are showing low or even negative employment growth (Chart 6).

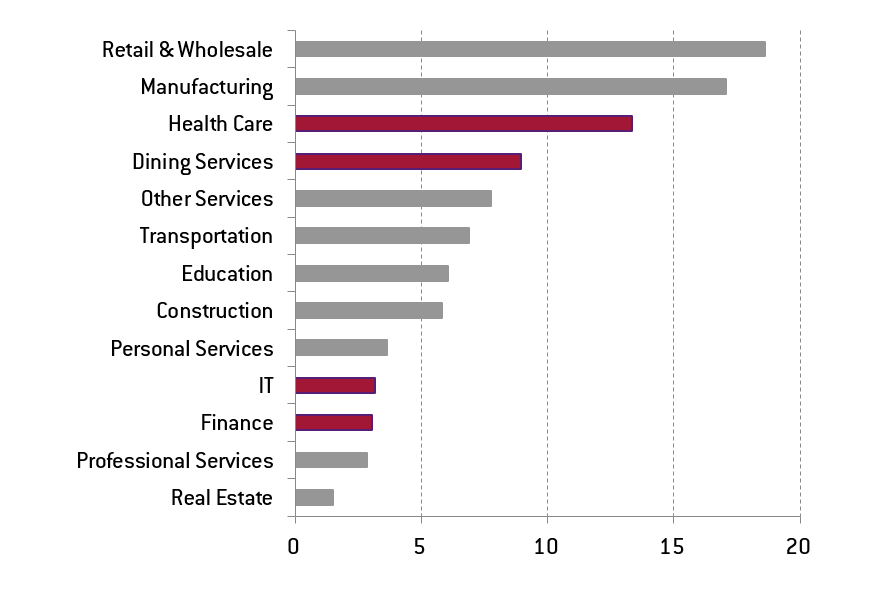

On the other hand, sectors with increasing employment such as health care and dining services are suffering from negative labour productivity. The reality is that these two sectors with negative labour productivity accounted for as much as 22% of the total employment in 2014 (Chart 7) and their share is growing.

The fact that they are creating employment much faster than the most productive sector explains how difficult it is for the Japanese economy as a whole to push productivity up. In fact, the overall productivity growth at the industry level is down to as little as +0.5% in 2014. The general negative relationship between productivity and employment is also reflected in wage growth. Wages in dining services and health are generally low, while those in finance and IT are high (Chart 8). Because finance and IT companies employ a small number of people, overall wage growth has also stagnated.

Chart 6 - Japan: Labour productivity & employment (2010-14, CAGR, %)

Sources: MHLW, Japan Productivity Center, NATIXIS

Chart 7 - Japan: Employment share by sector (%, 2014)

Sources : MHLW, NATIXIS

Chart 8 - Japan: Wages & employment by sector (2014)

Sources : MHLW, NATIXIS

The employment system

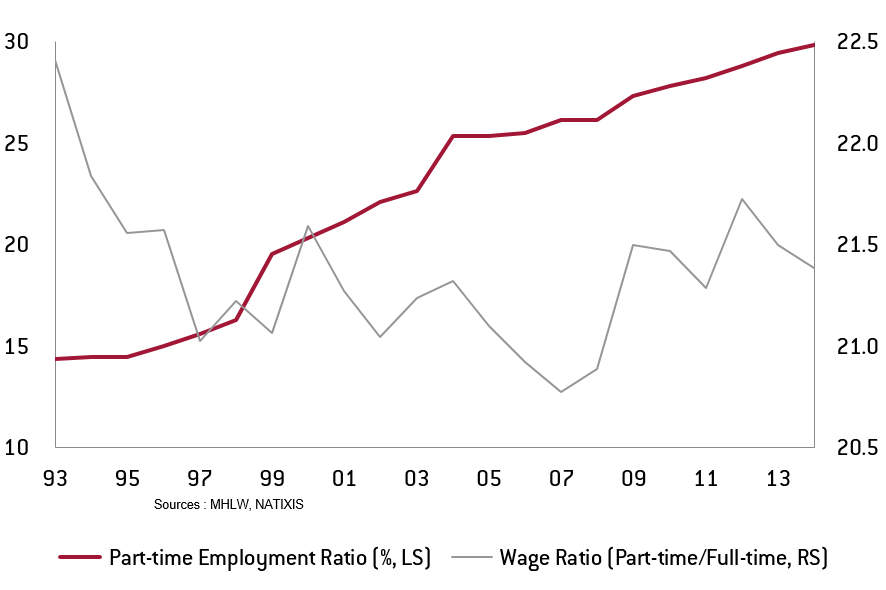

The Japanese labour market is far from efficient. It has become increasingly dual, with full-time and part-time workers subject to very different conditions, including wages. The much discussed principle of “equal pay for equal work” is not really in place in Japan.

Full-time jobs are in fact jobs for life, where the number of years of service at the firm is an important factor in determining wages for permanent staff. At the same time, the share of part-time employment has continued to increase, from 15% in the early 90s to 30% of total employment in 2014. Finally, the differences in wages between part-time and full-time employees has grown since the early 90s and hovers around 21.5%, meaning that labour related earnings for part-time employees are just over a fifth of those for full-time employees (Chart 9).

Chart 9 - Japan: Full-time vs. part-time (%)

Sources : MHLW, NATIXIS

Such a huge difference in wages masks the reality of Japan’s dual labour market. Most part-time workers in Japan are women who are raising a family, making up about 68% of the total in 2014. Furthermore, part-timers are actively taking those positions, even if they are less paid than the full-time ones (Chart 9). The top two reasons for taking such low-paid positions are “flexible working hours” and “supporting family income” according to existing surveys. Only 17% of respondents said they took such jobs because they could not find a full-time position. In other words, the government’s battle to increase wages is uphill, as low wages seem to be more of a personal choice than an obligation. However, the devil lies in the details or, better, on the incentives, as we shall explain later.

The “third arrow” is the key

When Japan’s Prime Minister Abe lunched his reform plan, Abenomics, he outlined three “arrows” needed for success. Beyond the first two (focused on monetary and fiscal demand policies), the third arrow focused on supply-side reforms.

So far, Abenomics’ third arrow seems to have focused on corporate tax cuts. The tax rate was cut in two consecutive years to 32.11% in April 2014, and the government has decided to further reduce it to 29.97% from April 2016. The lower tax environment may not be enough to discourage Japanese companies from producing abroad as this is also driven by structural reasons, in particular lower domestic demand given the aging population[1]. However, lower corporate tax rates should encourage companies to upgrade their old equipment and stimulate the much needed IT investments, especially among smaller firms.

Still, Abenomics’ third arrow will not go far if it only tackles corporate tax rates. Labour market reform is crucial to raise labour productivity and potential growth, but not much is happening. Prime Minister Abe has stated his support for the principle of “equal pay for equal work”, but no real measures have yet been taken.

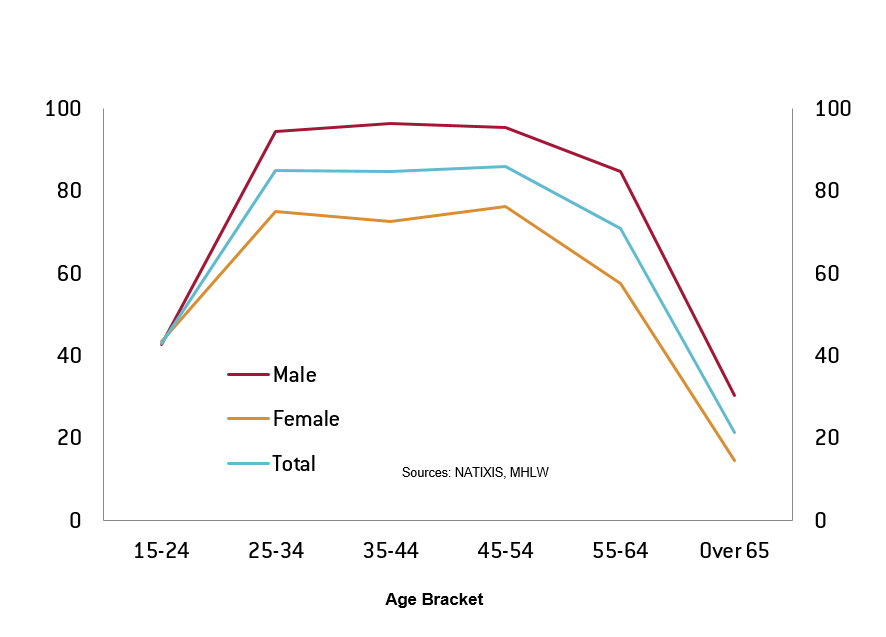

Reform is essential to increase the efficiency of the labour market, so that every individual can use their talents to the highest potential. Because an efficient market would attract and retain talented individuals, this principle is essential to encourage women to enter the labour market, as they could be more productive and so also earn higher wages.

Introducing the principle of equal pay in the labour market will require major reforms and, in particular, the elimination of the current dual system of full-time versus part-time workers. Given the extremely high legal protection that full-time workers have, this will certainly not be an easy reform for the Abe administration, which may explain the focus on corporate tax instead.

In addition to the “equal pay for equal work” strategy, the government should focus on the current fiscal distortions which may explain female workers’ willingness to accept much lower wages. In particular, part-time female participation is encouraged through tax exemptions (as long as the pay is below the maximum to enjoy such a tax break, namely JPY 1.03 million). This makes it unappealing for women to search for a full-time job, as the household would no longer benefit from the tax break.

It is hard to understand how such a distortionary tax system has survived so long. It was introduced in the 60s, when it was common for women to be full-time housewives in Japan. Today, the female participation rate remains well below that of men (Chart 10). Part of the reason is insufficient childcare facilities, and the government plans to double childcare capacity in three years. However, eliminating the current tax distortions and the dual labour market more generally could be more important.

Chart 10 - Japan: Labour participation (2014, %)

Sources : MHLW, NATIXIS

Lessons for Europe

The Japanese authorities are increasingly obsessed by raising wages, not only to increase inflation but also to raise households’ purchasing power and consumption. This is an important issue for Europe right now, as our economy risks heading towards the same low growth-low inflation paradigm that has characterized the Japanese economy during the last three decades.

Labour productivity is a key factor behind the disappointing growth in wages. A number of structural changes are behind Japan’s increasingly low productivity, including the creation of a dual labour market in which the more productive sectors, mostly in manufacturing, are not creating jobs, partially because of employees’ full protection under life-time employment rules.

On the other hand, the less productive service sector is creating most of the jobs. These jobs have much lower salaries and much more flexible contracts. European companies are facing a similar situation. This means that no matter how much the Japanese government puts pressure on companies to raise wages, it will not work. Even if larger corporations follow the government’s advice, the smaller companies creating most of the employment cannot follow suit, as the productivity is too low to justify wage increases.

Labour market reforms are urgently needed to increase labour productivity and therefore wages. First, policymakers must ensuring the principle of “equal pay for equal work”, eliminating the incentives to maintain a dual labour market. Second, they must get rid of distortions in the current income tax system which encourage women to take low-pay and part-time jobs.

These two measures would not only increase female participation in the labour market but also boost labour productivity and wages. This is easier said than done, as it involves eliminating Japan’s life-time employment system, which currently protects 70% of employees. Still, without such labour reforms, Abenomics will most likely end in a failure. It is important for Europe to draw lessons from Japan before it is too late.

I would like to thank Kohei Iwahara for his help on a longer piece which we wrote together on the same issue.