Spanish unemployment and the effects of the 2012 labour market reform

What’s at stake: Spain is currently the EU country with the second highest level of unemployment, after Greece. The high and persistent level of unemp

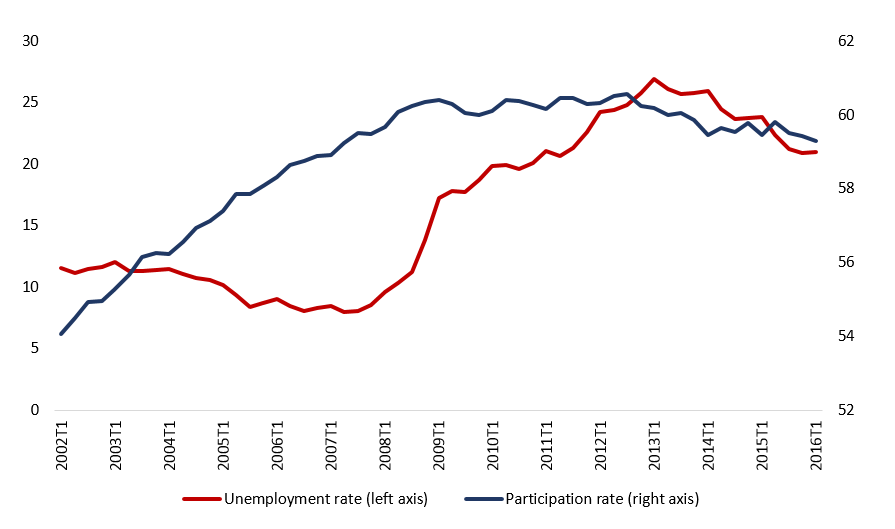

Note: Unemployment rate: share of unemployed over total active population between 16-64 years old; Participation rate: share of employed over total population between 16-64 years old.

Source: Spanish National Institute of Statistics (INE).

What are the reasons behind Spain’s high level of unemployment

William Chislett argues that the high unemployment rate in Spain is due to multiple factors. Firstly, he argues that Spain’s economic model excessively relied on the construction sector. When the property bubble burst, jobs were destroyed as quickly as they had been created. Moreover, this resulted in a banking crisis and a consequent credit crunch. Secondly, the labour market laws were too rigid before the crisis. Thirdly, education outcomes are poor in comparison to the rest of the EU. Finally, Spain experienced a massive immigration wave relative to its population size since the beginning of the 21st century. They were particularly needed in construction and agricultural sectors. When the economy went into recession, immigrants bore a large part of the surge in the unemployment, as many of them were on temporary contracts and were the first to lose their jobs.

Peter Eavis, writing for TheUpshot, highlighted the persistence of the high level of unemployment in Spain. The unemployment rate is currently at 20% and has been above this level for over five years (although it has gone down from 25% two years ago) even as the economy has been recovering. Spanish officials have said they do not expect the jobless rate to fall below 15% until 2019. Eavis argued that this is partly due to the huge share of temporary contracts (a third of Spain’s workers were on temporary contracts before the 2008 crisis), and to hysteresis effects as long-term unemployment is still very high (currently above 10% of the active population).

Matthew C. Klein points out that Spain’s peak-to-trough declines in employment and GDP were about the same as what you would expect for a US state that had a relatively large manufacturing sector and an enormous boom and bust in construction. Relative to the closest analogies he could find in the US, Spain actually did quite well considering the poor hand it was dealt — and that’s not even considering Spain’s limited policy flexibility thanks to its membership in the euro area.

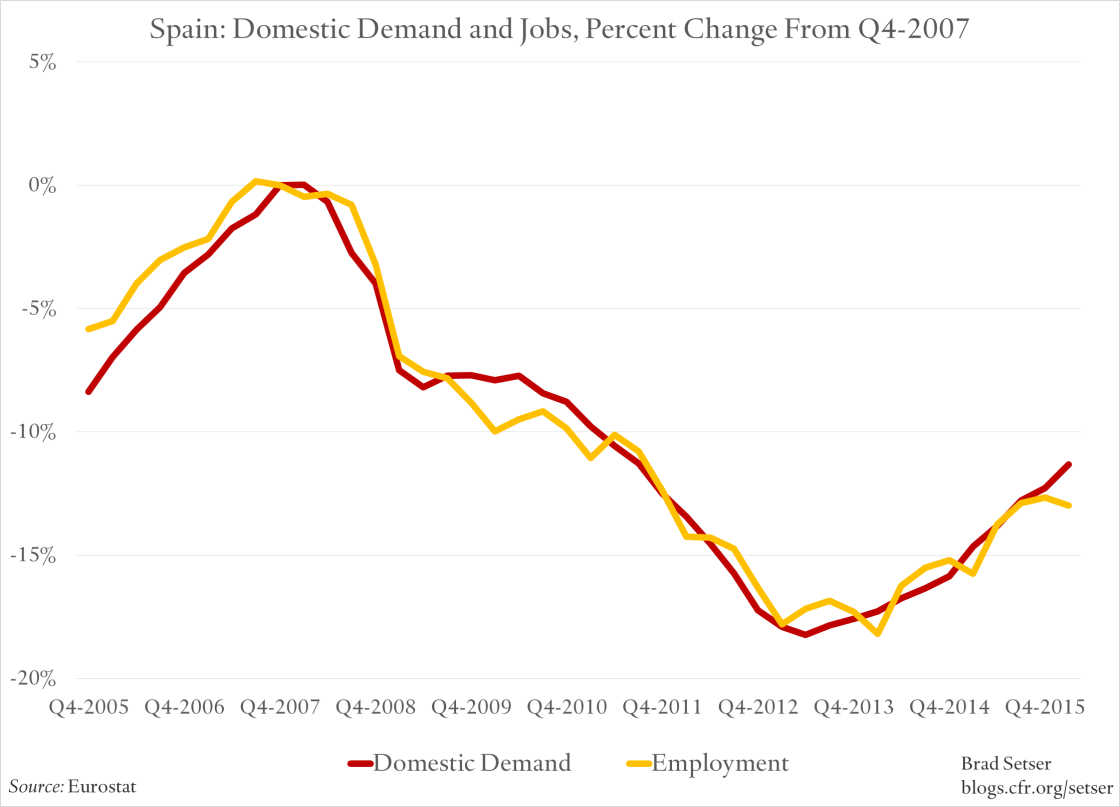

Brad Setser does not think there should be any significant debate over why Spain continues to have a very high level of unemployment: employment has been tracking internal demand, which remains more than 10% below the pre-crisis level (see the figure below). Spain needs policies in the euro area that would make adjustments in relative wages and prices possible without outright falls in Spanish prices and wages. That would allow external adjustment with less internal demand compression.

What have been the effects of the Spanish labour market reforms of 2012?

As Miguel Cardoso emphasises, four years constitute a very limited time window in economics to come up with a rigorous assessment of a policy change of this magnitude. A proper quantification of the Spanish labour market reforms requires controlling for cyclical components and external factors (QE, oil prices, economic recovery in the Eurozone, etc.). However, different studies attempt to control for these exogenous factors. Ignoring these results could lead to undesired consequences.

In a paper written in 2012, Juan Dolado analyses the reforms just after their approval, and warns not to expect too much from them. The reforms go in the right direction in achieving higher internal flexibility, but, on the negative side, they fail to be transformational enough in other relevant areas, like suppressing dualism, improving the effectiveness of active labour market policies, enhancing productivity and maintaining the overall level of social protection of Spanish workers. Given these limitations, he is sceptical that they will be the ultimate reforms curing once and for all the Spanish labour market “disease”.

The OECD released in late 2013 a preliminary assessment of the labour market reforms approved by PP’s government in 2012. The reforms benefited the Spanish economy in two ways: first, they increased the internal flexibility of firms by giving greater priority to collective bargaining agreements at the firm level over those at the sectorial or regional level. Although this led to a significant wage moderation affecting workers’ living standards, it contributed to safe jobs. Second, the labour reform significantly reduced the rigidity of the Spanish legislation on dismissals, giving firms incentives to hire permanent workers and dampening the widespread segmentation of the Spanish labour market between permanent and temporary workers. Their conclusion is that, although the labour reform represented a first step in order to boost competitiveness and productivity growth in the medium term, further steps should be taken in order to promote greater convergence of employers’ costs of termination for permanent and temporary workers.

José Ignacio García Pérez and Marcel Jansen agree with the OECD that the reform seems to have had a positive impact on internal flexibility and collective bargaining. However, regarding wage moderation, it is unclear to what degree this is due to the reform or to the wage restraint agreement signed in January of 2012. Finally, changes in hiring and dismissals seem insufficient to address the structural problem of duality and the reform failed to introduce necessary improvements of active labour market policies.

In August 2015, the International Monetary Fund published a preliminary assessment of the Spanish 2012 labour market reforms, and reached conclusions similar to those of the OECD: it led to wage growth moderation, an increase in wage flexibility, a slowdown in employment losses and eventually a positive net employment in the second quarter of 2014. The fact that employment started growing at a time of low GDP growth might have been a sign of more job-rich growth than in the past. Finally, it suggests that while there have been some improvements in shifting away from temporary towards permanent hires, this shift will have to be stronger and considerably more sustained to bring down the exceptionally high share of temporary workers.

In line with the IMF results, Fedea analyses whether the labour reform has managed to reduce dualism in the Spanish labour market. Their results suggest that this is indeed the case, as the labour reform has increased the probability of being hired with a permanent contract and has reduced the speed of job destruction among temporary workers due to the higher internal flexibility of firms.

Domenech, Ramón García and Ulloa, in a BBVA Working Paper, use a structural VAR model to assess the effects of the greater wage flexibility since the reforms. They conclude that these effects were significant. In fact, had the reforms not taken place, they estimate that the Spanish economy would currently be providing around 1 million less jobs, and the unemployment rate would currently be 5.1 percentage points higher. Conversely, entering the crisis with the current level of wage flexibility would have avoided the destruction of 2 million jobs, and the unemployment rate would now be 8 percentage points lower than it currently is.

The reading that the European Trade Union Institute makes of the labour reform is very different. The study concludes that the reform has not managed to mitigate the structural problem of labour market dualism, but instead has perpetuated long-term unemployment and reduced workers’ rights. Additionally, they compare the Spanish case with how Germany dealt with the decrease in domestic demand before the crisis. While in Spain the adjustment came through reductions in employment, active cooperation between employers’ associations and labour unions in Germany managed to negotiate reductions in working hours and salaries, alleviating the need to lay off workers. Their final point is that the Spanish labour market reform has not induced firms to adjust via working hours nor increased permanent contracts

The BNP Paribas Research Department writes that, although it is still too early to fully evaluate the impact of these reforms, they already seem to have had direct effects on wages (which have moderated) and employment (which has increased, but it is unclear whether this is due to the reforms). Nonetheless, companies continue to favour temporary job contracts. This means that job market’s duality will probably continue to hurt the Spanish economy. Employees with temporary contracts are less well-paid. They are more highly exposed to part-time work and benefit from less training than full-time employees. This lack of training in turn undermines their employability and increases the risk of job market exclusion.