China's political agenda for the G20 summit

Chairing the G20 offers China a unique opportunity to set the tone in global economic debates, and the Hangzhou summit is the focus of attention. The

China will host the next G20 summit on 4-5 September in Hangzhou. With the clock ticking, the world waits to see how China will use the meeting to promote its domestic development agenda and shape global economic governance. I predict China will have three key aims: strengthening its international role; promoting trade openness; and a global policy agenda of structural reforms coupled with fiscal support for demand.

China will have three key aims: strengthening its international role; promoting trade openness; and a global policy agenda of structural reforms coupled with fiscal support for demand.

I draw these concrete aims from China’s stated themes for its G20 Presidency, namely growth, interconnectivity and inclusiveness. A Chinese saying claims that "Hangzhou is heaven on earth", and the Chinese authorities will likely take advantage of this "paradise" to achieve their political goals. But are their objectives too far-fetched? Progress is difficult, especially at a time when the global economy is sluggish and stuck in a swamp where monetary policy seems to have lost its effectiveness. Only fiscal weapons are left, but that is only for the few fortunate economies which still have space. To judge just how realistic China’s targets for September’s G20 meeting might be, here is some detail on each of them.

Firstly, external trade is vital to support global growth — but especially growth in China. It is hard to find a country that has benefitted more from trade than China. Even though Beijing is rebalancing towards a consumption-based economy, China still needs to export at full capacity to keep growth at a high enough level. Protectionism is therefore one of the major risks to China’s successful economic transition. After the demise of the Doha round, and with China’s hugely increased negotiating power, bilateral trade agreements seem to have become China’s key policy tool to avoid protectionism. In any event, the G20 is a good place to remind global leaders of the importance of multilateralism and to widen the gains from international trade, which is still clearly in China’s interest.

The Chinese government will surely assert China’s relevance in global affairs and challenge the status quo.

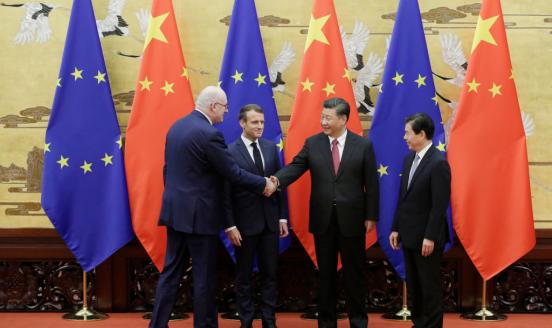

Secondly, China’s keen desire to strengthen its soft power will be on display at the G20 summit. In fact, the Chinese government will surely assert China’s relevance in global affairs and challenge the status quo. The G20 is a perfect venue to do this, because emerging countries are an integral part of the group and this naturally weakens US dominance. Emerging economies are likely to support China’s wider global role at the G20 meeting, especially because two of the key topics on the agenda (the Paris Agreement on climate change and the financing of the global infrastructure gap) should bring emerging countries together with a relatively united position. It goes without saying, however, that renewed tensions in the South China Sea may overshadow such common interest. There is a risk that countries will fear an increasingly revisionist China. That being said, China will probably use the summit to showcase its new international institutions, both the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank and the New Development Bank. Beijing will also want to promote its massively ambitious Belt and Road Initiative. The massive figures for Chinese outward direct investment, which have only accelerated since the beginning of 2016, are another sign of China’s rapidly increasing clout in the world, which supports a bigger role in the international financial architecture.

In the point of view of the Chinese government, high growth can be maintained through lax demand policies

Finally, China’s third key goal will be to stress the need for structural reforms while maintaining high growth. In the point of view of the Chinese government, high growth can be maintained through lax demand policies. In the absence of monetary space at the G7 level, the recipe is fiscal expansion for as long as there is space. For emerging economies, China will probably push for both. On structural reforms, President Xi’s latest push for a reform agenda, at least nominally, was outlined in the 13th Five-Year Plan. This should also serve as a basis for China’s call for structural reforms at the G20, so as to increase productivity at the global level. This point seems particularly important to me, because the developed world faces a number of challenges, such as high debt, low return on investment and an aging population, which only a productivity boost can overcome.

In short, we should expect China, as host of the upcoming G20 summit, to push for three key objectives, namely trade openness, a larger international role and structural reforms with lax demand policies. All three should find enough support from G20 participants, and thus appear in the communiqué. The real question, however, is how the G20 will really operationalise these objectives in the future. That is where China may have much less leeway, given the inter-governmental structure of the G20 and the lack of operational independence that such a body enjoys.