India’s economic journey: why should Europe care?

Which political and economic policy domains link India and Europe? Which key issues, challenges and debates are engaging the Modi government half-way

History and strategy

The Indian subcontinent and Europe have had human and commercial links since at least the time of Alexander the Great, more fully documented since Roman times. The depth of engagement, intellectual and strategic, increased dramatically in the age of exploration and colonisation. This engagement was clearly deepest with Great Britain, but France, Portugal, The Netherlands and even Denmark each had their sub-continental moment.

As Niall Ferguson (2003), among others, has pointed out, the Indian Army was central to the projection of British power in Africa. The centenary of the Great War has served to remind us of the involvement of Indian troops in the Imperial war effort from Passchendaele to Mesopotamia. Looking ahead Robert Kaplan (2011) has argued that the Indian Ocean promises to replace the Atlantic and perhaps even the Pacific as the major geopolitical arena in the 21st century. What is already apparent is a more intense engagement on maritime security between India, Japan and the United States, coupled with a significant broadening of arms suppliers beyond India’s traditional reliance on Russia. Britain, France and Sweden have been active in these discussions.

The Institutional Setting

India’s long-standing historical and cultural links with Europe are reflected in the legal and constitutional foundations of the country and in the widespread use of English as the core commercial and elite language.

Despite the enormous difference in levels of per capita income, debates on economic governance in Europe carry resonance for India. Both entities seek to engage diverse populations in a common economic enterprise within an accepted but still evolving set of democratic institutions. Both are committed to secularism in the presence of a single dominant religion. The Catholic/Protestant divide in Europe is loosely mirrored in the caste divisions within Hinduism. Both entities are affected by the stresses in modern Islam, both through their significant domestic Muslim populations (India at 14%; France 7.5%) and through their frontier with the Muslim heartland in the Middle East. India depends on that region for oil and has a substantial migrant presence there, whose remittances are an important source of income support to families in India and a significant support in the balance of payments.

The differences are also evident. India is a ‘union’ of its constituent states and territories, similar to a federation, whereas the EU is a club of sovereign nations agreeing to abide by a common set of values and rules, amenable to expansion to new members via an established enlargement process. Both entities are a product of the post-war, post-imperial economic order. India’s economic institutions owe their origin to the Indian constitution prepared by an elected constituent assembly after independence (and partition) in 1947 and embodied in an Indian republic that came into being in 1950. The EU has its origins in the coal and steel community of 1956 accepted by the original six sovereign states as a response to Europe’s changed global standing following the Second World War.

Despite these constitutional differences, both the EU and India face similar challenges in persuading proud, empowered and occasionally rebellious constituent jurisdictions to agree to common policies. The Indian constitution addresses the issue of ‘subsidiarity’ through three lists of legislative competencies: the Union list; the concurrent list; and the states list. Such matters as foreign policy and trade negotiations are in the Union list although the Union government occasionally consults with state governments in these areas. Conversely in controversial areas of economic reform, such as currently labour and land policy, where the Union government lacks a majority in the upper house of Parliament, individual states have been encouraged to take the lead in the expectation that competitive pressures would compel more reluctant states to fall into line.

Indo-European economic links

India is one of the ten strategic partners designated by the EU for periodic meetings at the summit level. The most recent between Prime Minister Modi and President Juncker of the Commission occurred in March 2016 following a three-year hiatus. India’s diplomats have traditionally preferred to engage with individual EU member states on both economic and political matters. India and Brussels also have the opportunity to interact within the framework of the G20 and its affiliated bodies, such as the Financial Stability Board (FSB). India enjoys particularly strong bilateral economic and political relationships with the UK, France and Germany.

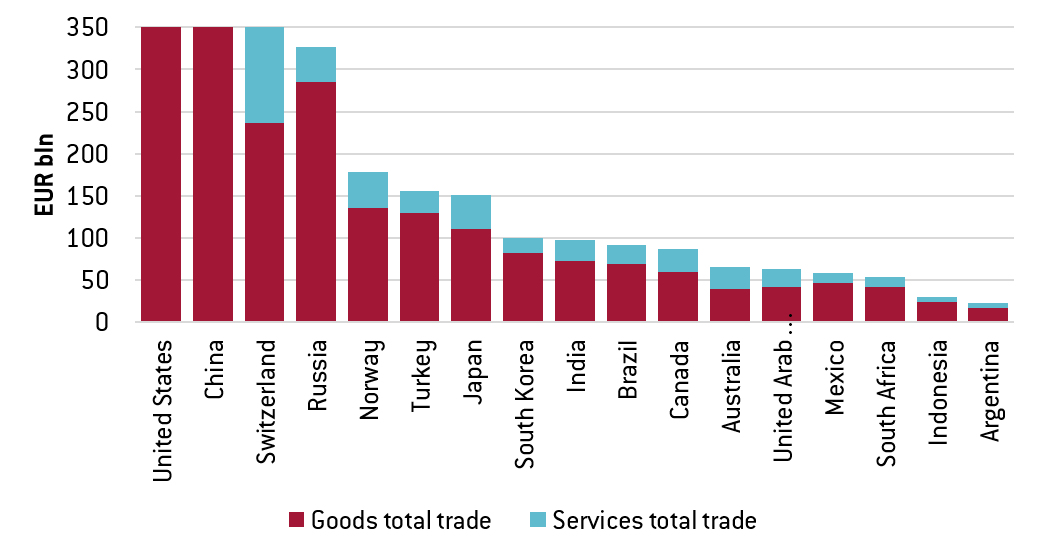

Trade is the main driver of the EU-India relationship. India’s total goods trade with the EU in 2015 was of the order of € 78 billion, making India the EU’s ninth biggest trading partner, after South Korea. Adding trade in services does not change the picture much: in 2014, the last year for which these data are available, India remains ninth, sandwiched between South Korea above and Brazil below. In that year it was a larger trading partner for the EU28 than was Canada (see Figure 1).

Collectively the EU28 are India’s largest trading partner (merchandise trade only). Indian sources cite Germany, Belgium and the UK as the principal country partners. India’s protracted negotiations with the EU on a broad-based trade and investment treaty (BTIA) made little progress at the recent Brussels summit. While India runs a sizeable trade deficit globally, its merchandise trade with the EU remains evenly balanced but has been stagnating in line with Europe’s recent sluggish growth. India’s relative dynamism as a services exporter is also not reflected in its trade with the EU.

Figure 1 - EU28 trade in goods and services by G20 partner, 2014 (selected countries, imports+exports)

Source: Eurostat, partner countries ranked by total trade in both goods and services.

The Modi government’s economic agenda

Following its victory in elections for the Lok Sabha (the lower house of Parliament) in May 2014 the Modi government is now at the halfway point of this Parliament. Prime Minister Modi achieved his electoral victory without previously having served at the Centre while his party had been out of office for a decade. It has taken time for the government’s economic and social priorities to be revealed.

Growth in real GDP is perhaps the most important aspect of India’s economic promise. In its World Economic Outlook (WEO) the IMF measures the contribution of individual countries to global economic activity by using weights at purchasing power parity (PPP). India’s estimated real GDP of $8.6tn (PPP) is just under half that of the US ($18.6tn.) and about 40% larger than that of Japan ($4.6tn.). An Indian economy growing at 7-plus percent thus provides a valuable complement to the contributions of the US and China in sustaining global growth and staving off deflation.

China’s rapid growth in the last decade has demonstrated that a poor but fast-growing large, open economy has an impact on the global economy through multiple channels. These include direct effects on global demand through the current account balance, which in the case of China has consistently been in surplus, but also via the impact on the terms of trade and global real interest rates. These cross-border influences are better assessed if measured at current prices and exchange rates.

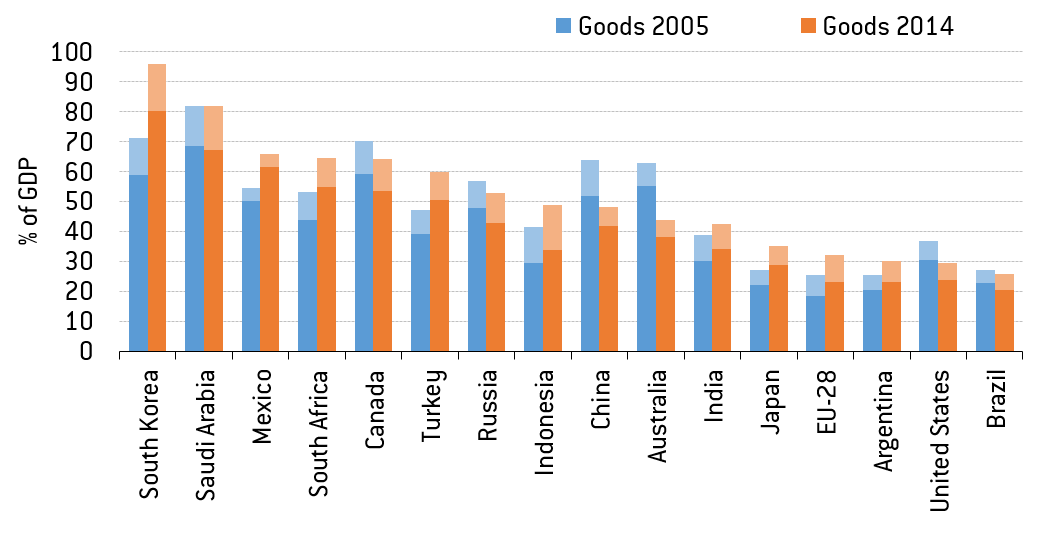

On this metric, India in 2016 is ranked by the IMF as the world’s seventh largest economy. At $2.3 tn. its economy is slightly larger than that of Italy and slightly smaller than that of France. For a country of its geographic expanse India is increasingly open to trade, considerably more so than the EU28, Japan or the US though less than commodity exporters Canada, Russia, Indonesia and Australia (see Figure 2).

Figure 2 - Trade in goods and services, 2005 and 2014, G20 countries

Source: Eurostat, countries ranked by 2014 sum of goods and services trade % of GDP.

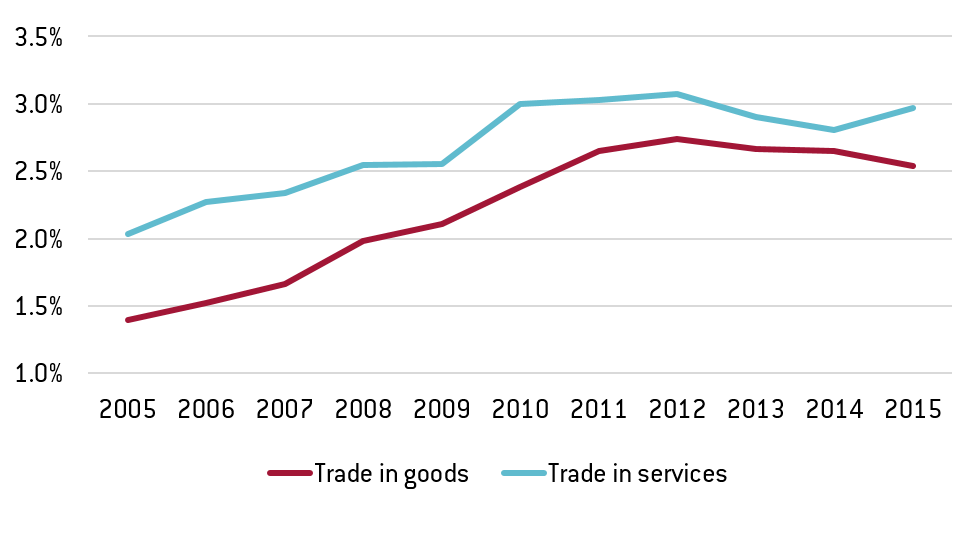

Figure 3 reveals that India’s share of global trade in services has been consistently higher than its share of global goods trade. Worryingly both seem to have plateaued in recent years. India’s financial system has also increased its international links over the past decade. Like China India retains some capital account restrictions and pursues a managed rather than market-driven exchange rate.

Figure 3 - India's share of world trade (exports+imports)

Source: OECD, ITC, WTO

For the Modi government sustaining fast economic growth matters for several reasons. The most important politically is to create better quality employment. Prime Minister Modi owes his electoral victory to an aspiring, restless and fast-growing cohort of youth, many voting for the first time. This electorate is increasingly connected through social media, a medium used skilfully both in the election campaign and by the government now that it is in power. Growth is a necessary though not sufficient condition for more and better jobs. It is for this reason that the Modi government has stressed the importance of manufacturing, technology, skill development and infrastructure as tools for enhancing the quality of growth.

These initiatives have been packaged in the government’s flagship “Make in India” initiative, launched in its first year in office. In contrast to its East and Southeast Asian peers India has not succeeded in maintaining double digit levels of manufacturing growth for any length of time. The efforts of the Modi government to promote Indian manufacturing output are in a long tradition dating back at least to 1956; it remains to be seen whether its considerable and concerted efforts meet with better success than those of the past.

A medium-term goal is to raise the share of manufacturing in GDP to levels comparable with India’s peers in Southeast Asia. According to World Bank data India’s share of manufacturing in GDP was 16%. This compares with 23% in Malaysia and 28% in Thailand, both of which are much more affluent than India. Global trends suggest that raising manufacturing employment will be even harder than raising the share of manufacturing output. Finally rapid economic growth is important to generate fiscal resources. These are needed to finance public investment and to improve India’s unimpressive record on human development. India as a whole lags even South Asian peers such as Bangladesh and Sri Lanka, even if some individual Indian states show equivalent performance. Credible prospects for sustained rapid growth should also make India a more attractive prospect for foreign investors. To its credit the current government is courting such investment more aggressively than ever before, even though it keeps tripping up on unresolved taxation disputes with multinationals on past transactions.

For all these reasons, as well as to reduce the economic distance with China in order to retain India’s strategic autonomy, the Modi government believes it must aim for GDP growth rates of 8% for the next two decades. Despite a serious cyclical slowdown in private corporate investment, related to over indebtedness in the previous boom, India’s investment rate has remained in the late twenties as a share of GDP, and could easily nudge back into the thirty-plus range attained before the financial crisis. Like its Asian counterparts and unlike Latin America, this investment is largely domestically financed, with a high household saving rate. India has benefited massively from the decline in crude oil prices, with an improvement in the terms of trade estimated by the IMF at 2.5% of GDP. India has also progressively liberalised outbound FDI, not because domestic investment opportunities have been exhausted, but rather to assist its domestic nonfinancial and financial firms in implementing their global corporate strategies.

If economic growth is the goal and manufacturing the focus, a key policy element in the emerging Modi economic strategy is fiscal reform. Starting from relatively modest beginnings at the start of the government this has assumed increasing ambition and multiple dimensions. The nuts and bolts will be examined in future posts, but the main elements include fiscal consolidation, a review of fiscal responsibility legislation (inter alia examining the fiscal rules established for the eurozone to ensure debt sustainability), devolution of shared revenues from the centre to the states as part of a broad thrust to decentralise economic decision making to the states; significant reform in the delivery of fuel and other subsidies; a review of expenditure management practices in the Union budget; a shift to outcome budgeting; and, most recently, attaining bipartisan parliamentary consensus for a constitutional amendment to integrate India’s multiple state and central systems of indirect tax into the start of a unified, destination-based VAT.

The parliamentary vote is the first step in a long journey. Critics argue that so many concessions have been made to enlist state and parliamentary support that the allocation, productivity, international competitiveness, corruption and revenue benefits of a more integrated system will be significantly eroded. Yet, as I argued in the Indian press at the time of the debate in the Upper House, the government’s success in approving the legislation carried enormous positive symbolic significance, both political and economic. It showed that the ruling coalition, the leading opposition party in parliament and the states could come together despite misgivings, distrust and conflicting interests to pass important economic legislation, and that the government was willing to expend important political capital for constructive ends. Developments since the August vote have by and large served to preserve this momentum.

I do not want to end this article sounding like Voltaire’s Dr Pangloss, assuming that all will be well in the face of multiple adversities. Even as it has become by one measure the world’s third largest economy, India remains by far the poorest member of the G20. Its attempt to achieve economic transformation through manufacturing-led growth takes place in a much more hostile global climate toward trade, investment and migration than faced its predecessors, and with a much greater awareness of the limited carrying capacity of the global environment. At home as well, the Modi government faces difficult legacy problems in its state-owned banks as well as dealing with chronically loss-making state-owned enterprises. I have already referred to India’s weak foundations in the health and education of its youth, which represent a massive undertow even in a rising tide.

My purpose of this introductory post has rather been to make the case that we have seen enough of the Modi government to suggest that interesting and important initiatives are underway. In a world of weak demand and low growth, what takes place in India should be of increasing interest to a European policy audience.

Future posts will look more deeply at themes of particular interest to the India-Europe economic relationship. These include trade policies and prospects, cross-border investment, financial sector governance and reform, technology and innovation policies, economic regulation, the management of urbanisation, the manufacturing challenge, fiscal decentralization and achieving growth while reflecting a carbon constraint.

I would like to thank Enrico Nano of Bruegel for excellent research support.

References

Ferguson (2003), Empire: How Britain made the modern world, Allen Lane, London.

Kaplan (2010), Monsoon: The Indian Ocean and the Future of American Power, Random House, New York, 2010