Why have export-oriented units in India failed to deliver?

In 1980, the Export Oriented Unit (EOU) Scheme was launched in India to boost exports and increase production. Though a number of provisions and exemp

The views expressed here are personal views of the authors and do not reflect the views of the organizations they belong to. We thank Mr. Devanjan Tyagi for research assistance.

1. Introduction

In 1965, India became the first country in Asia to set up an Export Processing Zone[3] (EPZ) at Kandla. Exactly after 15 years, in 1980, the Export Oriented Unit (EOU) Scheme was introduced to boost exports and increase production. The EOU scheme of government of India provides domestic economic units an internationally competitive duty free environment with better infrastructural and logistical facilities for exports promotion. The economic units/exporters are given specific locations with policy supports required for tariffs and non-tariffs barriers for easier trade activities. The main objective of EOU’s is to promote exports, earn foreign exchange, attract foreign investment and help technology transfers.

To facilitate better delivery on exports and foreign exchange, the scheme had a number of provisions[4] relating to customs, foreign trade, foreign exchange, service tax, etc. The scheme had many fiscal and non-fiscal incentives to ensure manufacturing quality and cost efficiency and, thereby, increase exports of value-added products. To encourage entrepreneurs to participate, the EOU Scheme included various incentives, including duty-free imports or domestic acquisition of capital goods/raw material/packaging materials and exemption of anti-dumping duties for inputs used in physical export and eligibility for domestic tariff area (DTA) sales within a specific limit.[5]

However, the EOU Scheme has not been successful, because of their limited size, lack of interest among local stakeholders, lack of promotion of the scheme, and limited share in the manufacturing sector (Sahoo et al, 2013). In 2007, the Comptroller and Auditor General of India (CAG[6]) conducted a performance audit of EOUs; it revealed that many EOUs were not performing well in achieving export targets and fulfilling net foreign exchange (NFE) obligations. Further, many EOUs were found evading central sales tax (CST) and exceeding DTA sales. In 2015, the report of another CAG performance audit of EOUs was submitted and tabled in parliament. The audit examined 370 EOUs over the period 2009–10 and 2013–14. The report—prepared in consultation with the Department of Commerce (DoC) and the Department of Revenue (DoR)—provides important leads to the existing policy framework, performance improvement, system issues to be solved, and other issues of non-compliance and misrepresentation with respect to EOUs. The performance evaluation brings out some startling facts on why EOUs have failed to deliver on their main objective, i.e., exports. Given that India’s exports have been declining for the past five quarters and that trade deficit has become a serious issue, it is time to relook at the EOU scheme.

2. Performance of EOUs and System Issues

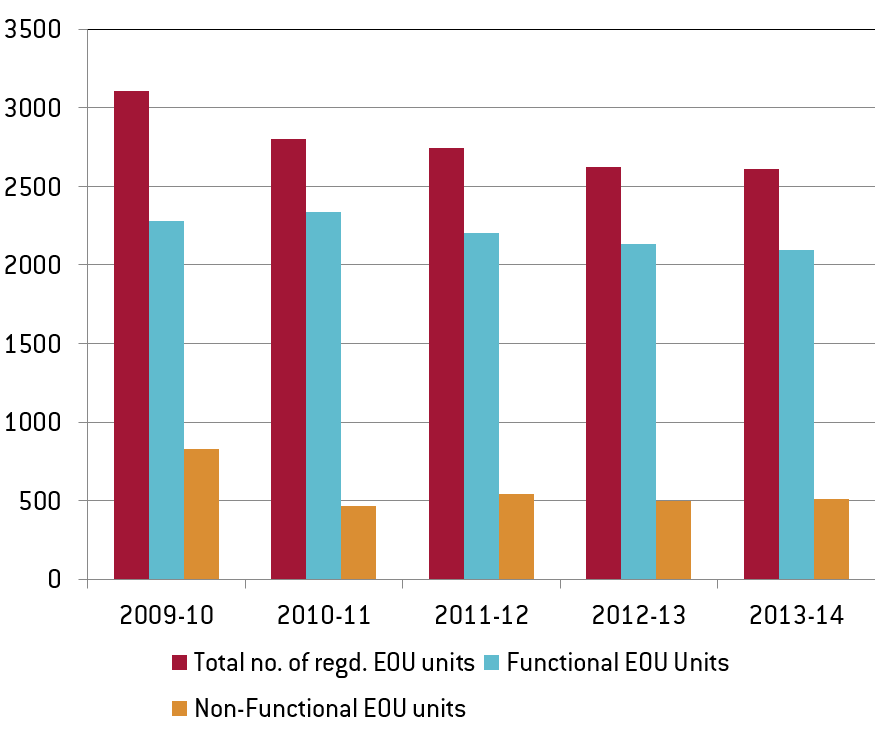

The growth of EOUs under the scheme (Figure 1) has witnessed a downward trend over the past few years.

Figure 1 EOUs in India

Source: CAG Report, Performance of 100 per cent EOU Scheme, 2014

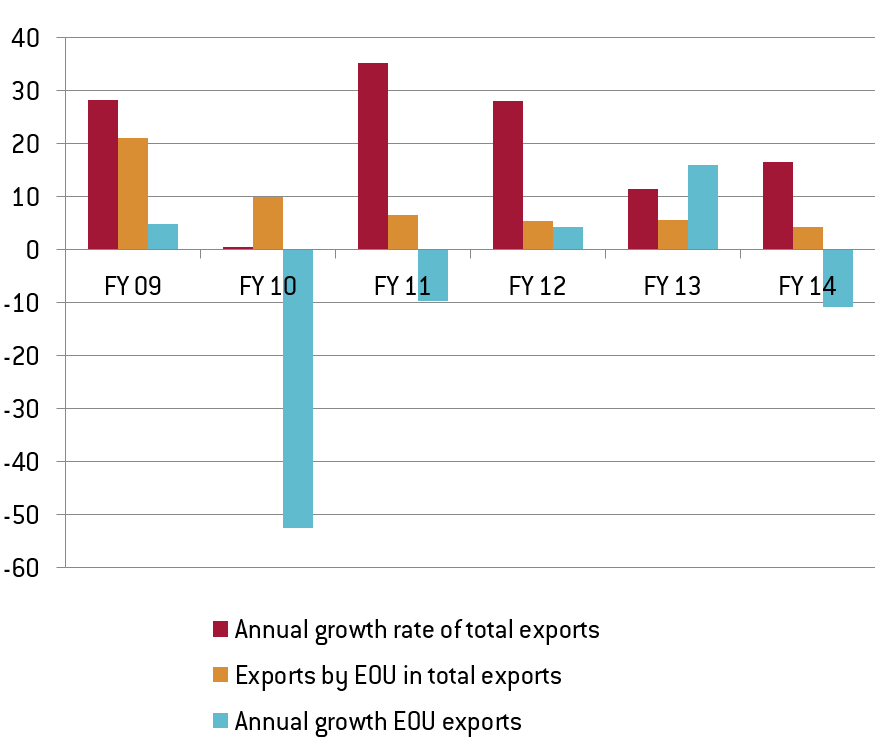

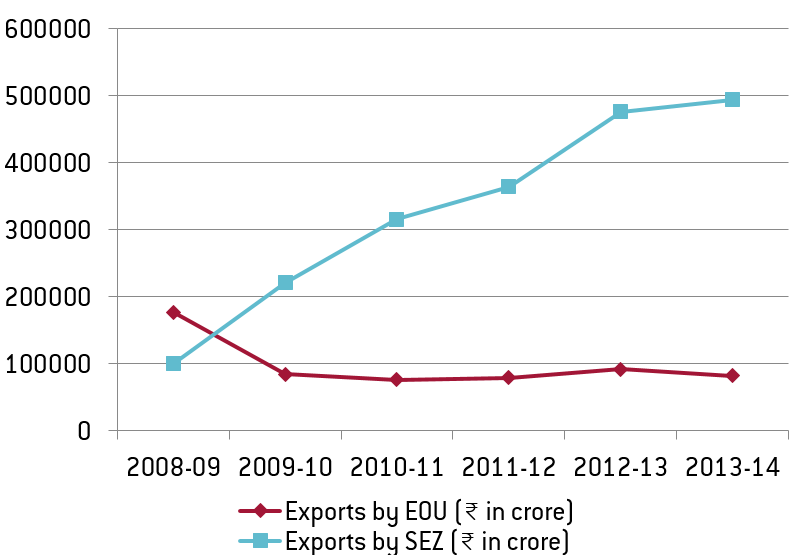

Though the proportion of non-functional EOUs have slowed marginally, they still constitute around 20 per cent of the total registered EOUs. The major reason for this downfall is the enactment of the Special Economic Zones (SEZ) Act, which came into effect in 2006–07, and the government’s inability (involving the FTP) to properly utilise the uniqueness of the 100-per-cent-EOU Scheme. Further, the performance of EOU exports in total exports has slowed drastically (Figure 2) and even turned negative in 2010–12. The declining growth of exports is the result of withdrawal of the tax benefits under the Income Tax Act, 1961 from 1 April 2011; as a result, EOUs opted out of this scheme. Unfortunately, there is no special provision in the FTP to utilise the unique advantages of the 100-per-cent-EOU Scheme, whereas similar export benefits were available to SEZs, along with allowance for domestic sales, but without any ceiling. Similarly, the Panda Committee[7] found that the EOU Scheme boomed during the 1980s, 1990s, and 2000s, but became less attractive to entrepreneurs after the SEZ Act, and even less so after the withdrawal of income tax benefits. As a result, the performance of EOUs has been declining vis-à-vis SEZs in the past few years (Figures 2 and 3). The contribution of from EOUs in India’s total exports increased from 11.5% in 2001 to 54% in 2008[8]. However, the share of EOUs in India’s total exports started falling since then. For example, the of share of EOUs was 21% in India’s total exports in 2009 which further declined to negligible 4.3% in 2014.

Figure 2 Performance of EOUs (2009–2014)

Source: CAG Report, Performance of 100 per cent EOU Scheme, 2014

Figure 3 Exports of SEZs vs. EOUs

Source: CAG Report, Performance of 100 per cent EOU Scheme, 2014

3. Lack of Regulation and Monitoring

The success of any scheme depends on proper regulation, auditing, and monitoring. However, and as observed by the CAG, the Ministry of Commerce and Industry (MOC&I) has not structured an internal audit mechanism[9] to check and facilitate the functioning of EOUs. Apart from the monitoring performed by the Development Commissioners (DCs), the administrative and supervising head, on quarterly/half-yearly/yearly performance, the Unit Approval Committee (UAC) monitors the Annual Progress Report[10] (APR), assessment report prepared annually about goals accomplished, resources used, project timeline, and budget. But the CAG observes that few EOUs submitted the APR during 2009–2013.

Further, the data on imports and exports reported to DCs does not match that reported to the Central Excise Department—it seems that the present policy does not require that the APR data be cross-checked with the Central Excise data or that deemed exports by EOUs be reflected in the APR. According to the central excise department, duty forgone and domestic procurement should be mentioned in the APRs but were not. This transparency was needed because, between 2009–10 and 2013–14, duty forgone on the EOU/EHTP/STP Scheme amounted to US $ 5 billion.

4. Cases of Non-compliance and Policy Misrepresentation

The audit observed various cases of misrepresentation and non-compliance during 2009–14. Around 48 cases of incorrect/irregular DTA sales were recorded, which involved short-/non-levy of duty of approximately around US $10 million. As per the scheme, EOUs can sell goods up to 50 per cent of the free-on-board (FoB) value of exports in DTA area conditioned to positive NFE. During the audit, nine EOUs under the Santa Cruz Electronics Export Promotion Zone (SEEPZ) and the Cochin Special Economic Zone (CSEZ) were found clearing individual products in excess of 90 per cent of FoB value into the DTA; this caused a duty loss to the government. As per the rule, separate accounts of indigenous and imported inputs have to be made to avail central excise duty exemptions. The audit invigilated 13 units that had not maintained separate accounts, leading to a loss of revenue to exchequer.

As per the FTP notification, the scrap/waste/remnants of the production process can be sold in the DTA with the payment of concessional duties. Some EOUs demanded full exemption on basic custom duty (BCD); later, it was found that they had not cleared the scrap. Often, EOUs do not pay anti-dumping duties, or maintain separate accounts but claim Central VAT (CENVAT) Credit, which leads to a loss to the exchequer.[11]

Other cases of non-compliance and misrepresentation by the EOUs include irregular reimbursement of CST and non-receipt of re-warehousing[12] certificates. The audit observed that units delayed their submission of re-warehousing certificates between 1 month to 73 months; the government had to forgo duty worth US $ 35 million. Similarly, in several cases, units imported and consumed goods/raw materials in excess of specified limits, and cost the government duty. Some other cases of non-compliance include violations of the conditions of the Letter of Purchase (LOP) [13] by EOUs. The audit reveals that in some cases the actual production of EOUs were in excess of the production projected in the LOP by 15.96 per cent and 1813.54 per cent. Similarly, units have been found procuring raw material and capital goods in excess of the limit approved in the LOP.[14] In several occasions, EOUs failed to realise foreign exchange even five years after commencing production. The respective DC/UAC also failed to monitor these cases, leading to a loss of US $ 13 million to the exchequer.

5. Steps for the Future

On the basis of the performance audit, the CAG provided a set of recommendations to make the working of EOUs effective and efficient.

- To achieve the desired export growth, the MOC&I could initiate policy measures to staunch the downward trend of EOU growth with specific timelines by utilising the uniqueness of EOUs.

- The DOC should implement an internal audit system to take the steps necessary to collect data and update it on dedicated website from time to time.

- The DOC should take steps to ensure that EOUs submit APRs timely and that those APRs contain all the relevant data related to exports, duty forgone, DTA sales, etc.

- The DOC must strengthen their internal control by improving joint monitoring by DCs and Central Excise authorities and also by fixing liability for any non-compliance with the various acts.

- The DOC has been advised to modify the provisions of the Foreign Trade Development and Regulations (FTD&R), 1992 Act to regulate the process/procedures in EOU linked to the objectives.

- To avoid contradictions between FTP and Central Excise notifications regarding DTA sales, the DOC may consider amending the provisions.

The SEZ Act, which is complementary to the EOU Act, came into force in 2005. An SEZ could be set up only in notified zones whereas an EOU could be established anywhere in India. The schemes had different objectives. While the EOU Scheme was announced earlier to boost exports by generating additional production capacity, the SEZ Scheme was introduced to attract investment, promote exports, and create employment opportunities. Both schemes provided similar incentives, but the performance of SEZs has also been far from satisfactory (CAG 2014; Sahoo 2015).

6. Conclusion and policy lessons

The main objective of exports promotion schemes like EOUs and SEZs is to promote exports. However, EOUs have been performing poorly over the past five years. In this context CAG brings out various systemic and policy issues relating to regulations, monitoring and co-ordination of various departments which come in the way of their optimum performance. The ambiguities and issues related to non-compliance and misrepresentation, and operational malfunction leads to huge losses to the government. To make the EOU Scheme succeed, the government could revise the scheme to suit the changing global environment and introduce new provisions to ensure proper functioning and monitoring.

There are a few lessons to be learnt in general. Mere announcement of multiple export promotion schemes like EOU and SEZ’s with plethora of benefits but with layers of rules and regulations without monitoring may not make exports competitive. What is required is policy streamlining with proper objectives and implementations. Isolated EOUs cannot be competitive when overall business and investment climate in the country does not improve hand in hand. EOUs are very small and sometimes opted by entrepreneurs only to get fiscal and other benefits without achieving the proposed objectives due to lack of clarity in policy and also proper monitoring process.

There are a few lessons to be learnt in general and for particular in Europe from the export promotion measures such as the export oriented units and special economic zone policies followed by emerging Asia. However, it must be noted the European economies especially the transitional economies in Europe are far more advanced in their levels of development as compared to emerging Asian Economies and may not benefit as much from emulating the policies in Asia. However, summarizing some of the experiences of export promotion policies in Asia, it is clear that the export booms underlying the Asian success stories, particularly Chinese success in SEZs, is largely attributable to the role that governments played in the development process. Governments invested heavily in infrastructure and provided subsidized utilities. At the early stages of development, efforts focused on transportation networks – roads, railroads, port facilities – along with electricity and telecommunications. Exporters were given access to inputs, capital goods and foreign exchange. Governments also are also concerned about enhancing the reputation of the country’s exports, and established regulations and licensing procedures to guarantee high quality.

Thus, a major policy lesson that could be drawn from the Indian EOU scheme for export promotion schemes is that an open and outward oriented trade regime is of central importance. A free-trade environment makes it easier to identify the economy’s comparative advantages and it gives exporters access to imported inputs at competitive prices. An open foreign direct investment regime is also important for export promotion. Along with open trade and investment policies, institutions for export credits, export insurance and guarantee schemes need to be developed.

EOUs and SEZ’s adopted by most emerging Asian economies including India could go a long way in enhancing exports provided the policies for export promotion are extremely clear to meet their objectives and there is institutional regulation and monitoring along with effective implementation. Export oriented units are a good way to promote SMEs enterprises in any economy as they are small in size and can be run successfully in clusters by small businesses and entrepreneurs. They are a good means to achieve the country’s export target.

References

Controller and Auditor General of India (21 of 2014). Performance of SEZs.

Controller and Auditor General of India (9 of 2015). Performance of 100% EOU Scheme.

Sahoo, P., Nataraj, G and Dash, R (2013) “Foreign direct investment in South Asia: Policy, Impact, Determinants and Challenges”, Springer.

Sahoo, P. (2015). “CAG Report on SEZ: Is it time to re-look at the SEZ Act?” Economic and Political Weekly 50 (14), 232–6.

[3] An economic zone or unit designed specifically for economic activities for the promotion of export.

[4] These are stated in the Foreign Trade Policy (FTP), Handbooks of Procedure (HBP), Central Excise Act 1944, Customs Act 1961, Foreign Exchange Management Act 1999, etc.

[5] The EOU Scheme has undergone various changes, including operating under custom bond and mandatory value addition specified in the Letter of Permission (LoP).

[6] CAG is a constitutional body which does audit of income and expenditure of both Central and State governments and carries performance audit of corporation, institutions etc that are supported by public exchequer. The CAG reports are submitted to parliament of India, particularly important committees like Public Accounts committee and committees on public undertaking.

[7] See report ‘Review and Revamp EOU Scehme’, Ministry of Commerce, Government of India, 2011.

[8] “Export oriented units (EOUs): a story of rise and fall”, The Dollar Business. ttps://www.thedollarbusiness.com/magazine/export-oriented-units-eous-a-story-o…

[9] Between 2009–10 and 2013–14, the Controller of Accounts and Audit did not conduct any internal audit at the field level or any other audit.

[10] The APR needs to be submitted within 90 days of the closure of the financial year. If it is not, further imports and DTA sales are rejected.

[11] The Central VAT (CENVAT) Credit Scheme lets manufacturers or output service providers set off taxes paid on inputs or input services used while manufacturing final products or providing the output service. According to the Cenvat Credit Rules, 2004, such set-off is not allowed on exempted goods, and units must maintain separate accounts for receipt, consumption, and inventory of input and input services used in manufacturing. Units that do not maintain separate accounts have to pay duty at 6 per cent of the total price charged by the manufacturer for the sale of such goods. Two units under the SEEPZ and six EOUs from the KSEZ were availed with CENVAT Credit amounting without maintaining separate accounts.

[12] Re-warehousing means removing goods from one warehouse to another. It requires the execution of a bond of an amount equivalent to the duty leviable on those goods.

[13] An LOP is considered authorisation for all purposes. Units that have an LOP must execute a Legal Undertaking (LUT) to abide with the terms of the LOP.

[14] In one case, a unit in the Falta Special Economic Zone (FSEZ) started production 11 years after the LOP was issued; the maximum gestation period is three years.