Brexit goes nuclear: The consequences of leaving Euratom

The UK Government has confirmed that it will withdraw from Euratom. But what does Euratom actually do? And what will happen when the UK leaves? The au

The UK Government has clarified with its Brexit White Paper that when invoking Article 50, it ‘will be leaving Euratom as well as the EU’. The need to distinguish exiting Euratom from exiting the EU arises because Euratom is legally distinct from the EU. The UK decided to leave Euratom because, albeit independent, the institution relies for its functioning on EU bodies such as the Commission, the Council of Ministers and the Court of Justice.

According to the White Paper, the UK Government considers the nuclear industry of strategic importance for the country, and for this reason it ‘will seek alternative arrangements’ to continue civil nuclear cooperation on safeguards, safety and trade with Europe.

In this blog we examine the functions of Euratom, its relevance for the UK, the potential implications of a UK departure from Euratom for both the UK and Euratom itself, and the potential ways forward.

Euratom: what is it and what does it do?

The European Atomic Energy Community (Euratom) was founded by the Treaties of Rome of 1957 with the aim of creating a European market for nuclear power. Euratom is legally distinct from the EU, although it is governed by EU institutions. Its membership is composed the EU Member States plus Switzerland (Associated State since 2014). Euratom also has cooperation agreements with eight “Third Countries”: US, Japan, Canada, Australia, Kazakhstan, Ukraine, Uzbekistan and South Africa.

The key functions of Euratom are to:

- Promote research on nuclear energy, and particularly on nuclear fusion – a technology that has the potential to provide a sustainable solution for the world’s energy needs and could thus be considered a global common good;

- Establish uniform safety standards and ensure that they are applied;

- Ensure the regular supply of ores and nuclear fuels;

- Ensure that nuclear materials are not diverted to purposes other than those for which they are intended;

- Ensure free movement of capital for investment in nuclear energy and free movement of employment for specialists in the sector.

Euratom carries out these functions using three key instruments:

- The Euratom Supplies Agency, which owns and controls the supply of all fissile materials in Euratom’s Member States;

- The European Commission, which develops research programmes to foster research on nuclear energy;

- The Euratom Safeguards Directorate, which ensures that nuclear materials are not diverted from their intended uses (non-proliferation).

The UK’s links to Euratom

Reflecting the key functions of Euratom, the UK’s links with the organisation are in the following areas:

Nuclear fusion research: Euratom’s flagship project is the ‘International Thermonuclear Experimental Reactor’ (ITER), the world’s largest planned nuclear fusion experiment. Located in the south of France, ITER is designed to produce 500 MW of fusion power from 50 MW of input power: a ten-fold return on energy. It is funded and run by a seven-party consortium composed of the EU, India, Japan, China, Russia, South Korea and the US.

The UK has an important role in this project. It hosts the Joint European Torus (JET), the world’s largest operational nuclear fusion device. This project is also known as ‘Little ITER’, since its experimental design and results are mainly supposed to consolidate ITER’s design. The JET project - carried out by a team of 350 scientists - is formally a joint venture used by more than 40 EU laboratories.

Budget for nuclear fusion: The EU is covering the largest share of ITER’s construction costs (45 percent), amounting to €2.7 billion over the 2014-2020 period. This is financed through a specific budget line within the Multiannual Financial Framework (MFF) of the EU budget. During the forthcoming negotiations, the European Commission is expected to claim the UK’s share of this amount as a liability towards the EU.

In addition, ITER-related research costs are covered through the EU Framework Programme for Research and Innovation (Horizon2020, formerly FP7), administered by Euratom. The UK stands to lose access to those funds.

To put it into perspective, over the 2014-18 period Euratom has a total research budget of €1.6 billion drawn from the H2020 budget, of which €700 million will be distributed to carry out research specifically on nuclear fusion. €424 million will go to EUROfusion, a consortium of university groups and national labs, mostly for research related to the ITER project. The remaining €283 million have been budgeted solely for the Culham Centre, the UK institute that hosts JET, operating as a common facility for researchers across Europe. JET alone receives around €69 million per year of funding, 87.5% of which is provided by the European Commission and the remaining 12.5 percent is funded by the UK.

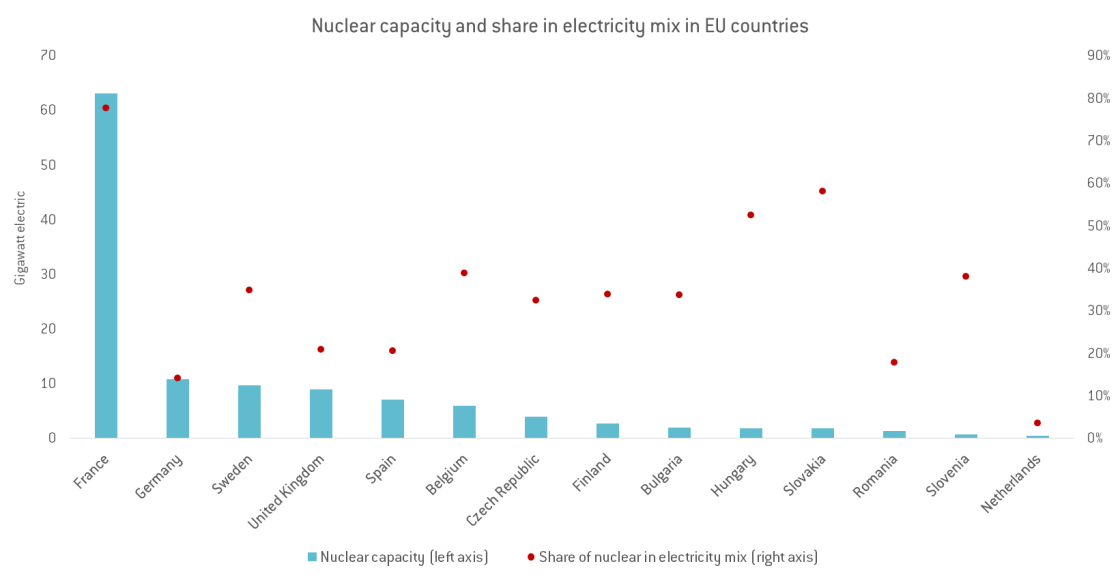

Safety, non-proliferation and free movement of capital and labour: Euratom is not only relevant to the UK for its research component, but also for its operational functions. The UK is historically highly dependent on nuclear energy. As of 2016, nuclear accounts for around 21% of the UK’s electricity generation mix. With its 15 nuclear reactors in operation, the UK ranks 2nd in the EU by number of nuclear power plants (after France) and 4th in terms of nuclear power capacity (after France, Germany and Sweden).

As a nuclear country, the UK thus relies on Euratom for activities related to safety at nuclear power plants, the supply of nuclear fuels and non-proliferation. Euratom is an established legislative framework for issues, such as free movement of capital for nuclear investments and free movement of labour for nuclear specialists, which facilitate investment in the sector and reduce costs associated with nuclear power generation.

By leaving Euratom, the UK might lose this package of advantages. This might have an impact not only on the UK’s operating nuclear power plants, but also on new projects under development. This includes the controversial Hinkley Point mega-project, which was finally approved by the UK Government in September 2016.

Supply of nuclear fuel: Under the Euratom Treaty, the Euratom Supplies Agency is endowed with a right of option on ores, source materials and special fissile materials produced in the territories of Member States. It also has an exclusive right to conclude contracts relating to the supply of ores, source materials and special fissile materials coming from inside or outside the Community. This common purchasing scheme gives the Euratom Community more bargaining power when negotiating contracts with external suppliers of nuclear fuels, thus contributing to the reduction of nuclear power generation costs. By leaving Euratom, the UK might lose also this economic advantage.

Source: IEA World Energy Balances, European Nuclear Society

Brexit from Euratom: potential impacts on the UK’s nuclear sector

The decision to leave Euratom could impact the UK’s nuclear industry in several ways:

Nuclear fusion research: Although the JET program is not likely to be affected before the end of 2018, its subsequent status is currently in a legal limbo. JET’s experiments may be halted or seriously delayed and, as a result, the ITER project could also be slowed down, because it is highly dependent on the JET’s outcomes;

Safety and non-proliferation: The UK Government would have to budget additional costs to run an autonomous system to guarantee appropriate safety standards, in particular for nuclear safety inspections. On leaving Euratom, the UK would also need to set up the proper framework to comply with its nuclear non-proliferation safeguards commitment and to decommission radioactive waste. The JET facilities alone, for instance, have produced some 3000 cubic meters of radioactive waste, which will cost about €336 million to decommission. This is currently provided for through an EU-wide cost-sharing arrangement.

Free movement of capital and labour: The Brexit announcement caught the scientific community unprepared and caused large disquiet, with researchers now considering to leave the UK. According to Prof. Steve Cowley, former CEO of the UK Atomic Energy Authority, the possibility of losing EU funding puts at risk more than 1000 clean-energy exploration jobs. It also risks a loss of expertise well beyond that at the JET-hosting Culham Centre, possibly impacting the research and tertiary education sector at large.

Furthermore, labour movement and trade restrictions may also have implications for the construction costs and schedule of new projects. Long negotiations could impose severe delays on new facilities, such as Hinkley Point C. This could increase general nuclear costs and also the risk that the UK will not hit its targets for reducing greenhouse gas emissions.

Supply of nuclear fuels: Currently the Euratom Supply Agency guarantees equal access to nuclear raw materials to the Member States. By pulling out of Euratom, the UK will have to re-negotiate commercial contracts to ensure provision of nuclear fuel, ores and fissile materials. Outside of the EU it is debatable whether the UK will have similar bargaining capacity to negotiate with others, a fact that may lead to higher costs for nuclear power generation in the UK.

Other legal issues: Euratom currently has about 20 nuclear cooperation agreements with third countries around the world, which the UK will have to re-negotiate. Of crucial importance are those with the International Atomic Energy Agency, the world's intergovernmental body for co-operation in the nuclear field, and with the US, from which the UK is a substantial importer of technology and fuel for its nuclear reactors.

Possible ways forward

Looking ahead, there are three possible scenarios for the post-Brexit UK-Euratom relationship. These should could offer broad frameworks for cooperation to be taken into consideration during the forthcoming negotiations:

1. UK out of Euratom: In this scenario, the UK Government would have neither obligations nor rights towards Euratom. As a result, the UK might ultimately see increasing costs for its nuclear power generation, due to the additional operational costs and supply costs deriving from being outside the established framework of Euratom. Furthermore, new projects such as Hinkley Point might also be delayed, due to the volatile climate investment that this scenario could generate.

As far as the EU is concerned, this scenario would not imply any additional costs, but only a potential delay in the nuclear fusion research at ITER, due to the potential unravelling of the JET project.

2. UK working with Euratom as a third country: According to Article 101 of the Euratom Treaty, ‘The Euratom Community may, within the limits of its powers and jurisdiction, enter into obligations by concluding agreements or contracts with a third ”state, an international organisation or a national of a third state’.

By acquiring the status of third country, the UK might join countries such as China and Russia, with which Euratom has established a ‘structured dialogue to identify a common set of research topics of mutual interest in which cooperation can take place on a shared-cost basis’;

3. UK in Euratom as Associated Country: According to Article 206 of the Euratom Treaty, ‘The Community may conclude with one or more States or international organisations agreements establishing an association involving reciprocal rights and obligations, common action and special procedures’. It is on the basis of this article that Switzerland became in 2014 an Associated Country to Euratom.