Questionable immigration claims in the Brexit white paper

The UK government's white paper on Brexit suggested that the EU's "free movement of people" has made it impossible to control immigration. This seems

Immigration to the UK was a key issue in the Brexit debate and has also received a great deal of attention since the referendum. According to the recent white paper from the UK Government on Brexit principles, control of immigration will be a key priority.

Point 5.3 of the white paper states that “It is simply not possible to control immigration overall when there is unlimited free movement of people to the UK from the EU”, suggesting that EU mobility rules were responsible for the surge in immigration and the UK did not have a control.

I find this claim potentially misleading, for two reasons:

- By respecting all EU rules, net immigration of non-British citizens to the UK could have been cut by a stunning 82% in 2004-11 and also rather significantly since then. It was a UK decision not to control immigration.

- EU rules allow unlimited free movement of people only for a duration up to three months. For longer periods, only workers, the very rich and students can stay in another EU country.

Let me elaborate on these two points and then draw lessons for future UK immigration policies.

UK decisions have led to the surge in immigration since the mid-1990s, not the EU’s labour mobility principle

The striking message of Figure 1 is that the bulk of immigrants to the UK since 1991 arrived from outside the EU.

Note: Figure 1 replicates Chart 5.1 of the white paper in a colourful way for better readability.

On average, in 2004-11, 71% of non-British immigrants arrived from outside the EU. Their ratio was still as high as 65% in 2012 and 52% on average in 2013-15. No EU rule forced the UK to admit so many non-EU citizens: it was a UK decision.

In these figures we should distinguish asylum seekers, who were allowed to enter the UK on humanitarian grounds. On average in 2004-11, asylum seekers accounted for 5% of non-British immigrants, while their share was 7% in 2013-15. Thereby, if the UK was interested in mitigating the inflow of people from non-EU countries beyond asylum seekers, UK authorities could have cut immigration by 66% in 2004-11 and 45% in 2013-15.

Certainly, in the event of temporary immigration restrictions on EU8 nationals in 2004-11 by the UK, citizens of these countries could have come to the UK after the end of the seven-year period. However, most likely, many of those EU8 citizens who actually immigrated to the UK in 2004-11 would have immigrated to other EU15 countries and settled there and therefore the imposition of seven-year temporary controls by the UK would have likely reduced total immigration from these countries significantly.

Moreover, the accession treaties with new EU member states allowed a transition period of up to seven years, during which older EU member states had the option to maintain immigration restrictions on the citizens of newer member states. They also had the option to introduce such controls during the seven-year transition period, even if they have abolished the restrictions earlier, provided that there was a serious disturbance on their labour markets.

Twelve of the fifteen other older EU member states used this option and adopted temporary immigration controls, but the UK, Ireland and Sweden opened their labour markets directly from 1 May 2004 for nationals of the eight central European countries (EU8) that joined the EU on 1 May 2004. Furthermore, the UK did not introduce controls later in the 7-year transition period, when immigration from these countries sharply increased. Immigration from EU8 accounted for on average 16% of non-British net immigration in 2004-11.

Therefore, even when respecting all EU rules, 2004-11 net immigration of non-British citizens to the UK could have been cut by a stunning 82% (71% non-EU minus 5% asylum seekers plus 16% EU8). But UK authorities decided not to do that.

The UK Government’s white paper does not even mention these facts, but seems to blame EU mobility rules for the surge in net immigration since the mid-1990s. This is simply incorrect.

In my view, there are various possible reasons why the UK government allowed immigration to increase from the mid-1990. These include both economic and political factors.

Firstly, these immigrants brought major economic benefits to the UK, which is also recognised by the white paper (see points 5.2, 5.5, 5.6, 5.7 and 5.8). I also wrote a post on this issue before the Brexit referendum. Political reasons could include a desire to support and welcome citizens of Commonwealth countries (who accounted for about half of non-EU immigration). There might also have been a recognition of Western European countries’ historical responsibility to re-unite the continent after the disastrous decades of communism in Central Europe. Or perhaps the UK wanted to show a “pro-European” face.

EU free mobility rules do not allow unlimited establishment of residency in other EU countries

The sentence I quoted from the white paper at the start of my blogpost talks about “unlimited free movement of people to the UK from the EU”. There is also a box on page 28 explaining EU’s mobility rules, which concludes: “The Free Movement Directive[15] sets out the rights of EU citizens and their family members to move and reside freely within the territory of the EU. This Directive replaced most of the previous European legislation facilitating the migration of the economically active and it consolidated the rights of EU citizens and their family members to move and reside freely within the territory of the EU.”

These statements greatly exaggerate the options available to EU citizens and are therefore potentially misleading. EU mobility rules, as set out in the Free Movement Directive, continue to focus on mobility of workers.

There is indeed unlimited free movement of tourists, and any citizen of an EU country can stay in another EU country for a period of three months without conditions.

However, a citizen of an EU country can stay in another EU country for more than three months only in three cases:

- If she/he finds a job (becomes employed or self-employed), or

- If she/he and accompanying family have sufficient resources and sickness insurance and do not become a burden on the social assistance system of the host member state, or

- If she/he has a student status and sufficient resources to cover living expenses and sickness insurance.

New jobseekers have a slightly more preferential treatment. Following European Court of Justice rulings, they can stay up to six (and not three) months. However, a six-month period is not that long and after six months host country authorities can ask the jobseeker to leave if she/he cannot prove to have a realistic chance of finding work there (see here). Host country authorities can also expel the jobseeker, although this cannot be an automatic process and all relevant circumstances have to be considered.

Therefore, the free residency right can be exercised unconditionally only for a period up to three months, for jobseekers up to six months. But only workers (and their family members), students and the very rich who do not rely on the social assistance system of the host country can stay for longer. Permanent residency is acquired only after a continuous period of five years legal residency according to the conditions described above.

These EU rules have important implications for a possible surge in immigration prior to Brexit:

The UK should not worry that much about a possible surge in immigration from EU countries prior to Brexit

Even if immigration from EU countries surges before Brexit, it is unlikely that those who come in excess of regular immigration patterns would find a job. There is a natural rate of job creation. Therefore, those new immigrants who are not able to find a job will become unauthorised after six months, and if they do not leave voluntarily, the UK will have to right to expel them.

What to conclude for the new UK immigration system after Brexit?

The economic reasons for allowing immigration to increase from the mid-1990 prevail. When labour shortages arise, authorities can either allow foreign nationals to enter, or to create tensions in the labour market and cut economic growth, which would have negative feedback effects on UK public finances and taxes paid by British citizens.

The ‘Global Britain’ vision of Prime Minister Theresa May involves attracting foreign investment, which will come with people. For example, when a US financial conglomerate establishes an office in the City of London, it will bring many employees from abroad. When a Japanese manufacturer establishes a factory in the UK, it will again bring many workers. In the age of digitalisation, IT investments will require more and more IT experts from India and other parts of the world, simply because there are not enough within the UK.

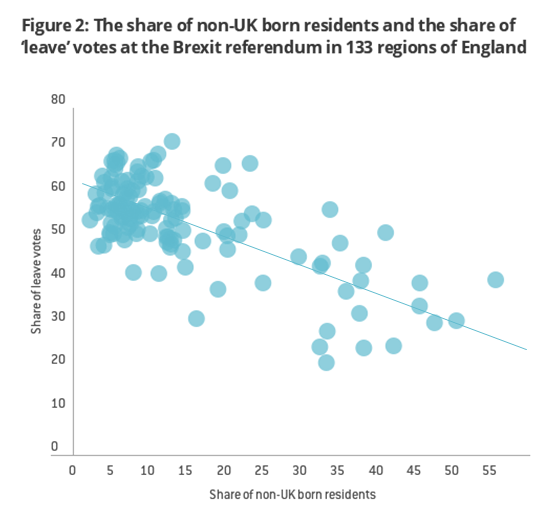

The next question is the immigration control mandate UK authorities received from the Brexit referendum. It is difficult to infer public opinion about immigration and what kind of control the majority of UK nationals would like to see. We only know that the share of leave votes at the Brexit referendum was actually lower in areas where there are more immigrants (Figure 2). This suggests that voters in areas where there are more immigrants were more in favour of EU-membership and possibly of the free labour mobility principle which comes with it.

Note: the dots represent the 133 NUTS3 regions of England, while the line shows the regression line. The same relationship holds within Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland.

Sources: The Electoral Commission and Office for National Statistics (see detailed data sources in the annex here).

There are compelling economic reasons in favour of immigration, and the Brexit referendum gave an ambiguous message about the UK’s future immigration policy. I therefore suggest that the UK should not introduce an overly tight immigration control system.

This post is partly based on my testimony at the House of Lords EU committee on UK-EU immigration issues on 18 January 2017. I thank Inês Goncalves Raposo for her great help in my preparation for the testimony.