Do we understand the impact of artificial intelligence on employment?

Artificial intelligence is already transforming the world of work, but the future is hard to predict. Some see most jobs at risk of automatisation, wh

In my previous blog on artificial intelligence (AI), I dealt with the general characteristics of AI and machine learning. Thanks to complex virtual learning techniques, machines are now able to perform a wide range of physical and cognitive tasks. And the efficiency and accuracy of their work is expected to increase as AI systems advance through machine learning, big data and increased computational power.

The benefits are clear, but there are also concerns for the future of human work and employment. If indeed machines continue to improve their performance beyond human levels, a natural question to ask is whether machines will put humans’ jobs at risk and reduce employment. Such a concern is not new but in fact dates back to the 1930s, when John Maynard Keynes postulated his “technological unemployment” theory.

In general, automation affects employment in two opposing ways:

- Negatively - by directly displacing workers from tasks they were previously performing (displacement effect)

- Positively – by increasing the demand for labour in other industries or jobs that arise due to automation (productivity effect)

So, the real question is which of the two effects will dominate in the AI era. Before we deal with this question, let’s travel back in time to previous industrial revolutions. Some interesting case studies are reported by The Economist:

- During the 19th century, the amount of coarse cloth a single weaver in America could produce in an hour increased by a factor of 50, while the amount of labour required per yard of cloth fell by 98%. However, the result was that cloth became cheaper, and demand for it increased. This created four times more jobs in the long run.

- The introduction of automobiles in daily life led to a decline in horse-related jobs. However, new industries emerged resulting in a positive impact on employment. It was not only that the automobile industry itself grew fast, increasing the available jobs in the sector. Jobs were also created in different sectors because of the growing number of vehicles on the roads. For example, new jobs were created in the motel and fast-food industries that arose to serve motorists and truck drivers.

So, past cases suggest that in the short run the displacement effect may dominate. But, in the longer run, when markets and society are fully adapted to major automation shocks, the productivity effect can dominate and lead to a positive impact on employment.

The invention of cars and automatic looms was long ago, but the Economist article also presents similar case studies of more recent technological developments.

- The introduction of software capable of analysing large volumes of legal documents reduced the cost of search but increased demand for it. As a result, the number of legal clerks (who before the implementation of the software had to search for the legal documents manually in a more time consuming way) increased by 1.1% on average per year between 2000 and 2013 instead of decreasing due to the displacement effect.

- Automated teller machines (ATMs) might have been expected to significantly reduce the number of bank clerks by taking over some of their routine tasks. Indeed, in the USA their average number fell from 20 per branch in 1988 to 13 in 2004. But that also reduced the cost of running a bank branch, allowing banks to open more branches in response to customer demand. The number of urban bank branches rose by 43% over the same period, so the total number of employees increased.

So, even in more recent examples, we see that technology leads to new employment opportunities in a way that we could not even imagine few decades ago. The automation of shopping through e-commerce, along with more accurate recommendations, encourages people to buy more and has increased overall employment in retail. (The annual growth of e-commerce in Europe is 22%. See Marcus and Petropoulos, 2016 for relevant statistics and policy discussion.) People can also generate income by supplying services on collaborative economy platforms where the entry barriers are very low. And people can further utilise available assets in an efficient way through the supply-demand matching algorithms in place.

Should we expect that the impact of AI on employment to follow similar patterns? Perhaps not. The McKinsey Global Institute estimates that, compared with the Industrial Revolution of the late 18th and early 19th centuries, AI’s disruption of society is happening ten times faster and at 300 times the scale. That means roughly 3000 times the impact. This very fast technological progress in the AI era raises the question: Is this time different?

Nevertheless, it is difficult to answer this question in a clear and convincing way. Reviewing recent research and economic analyses we see that there is no consensus on the impact of automation on employment.

Acemoglu and Restrepo (2017) deal with industrial robots (“an automatically controlled, reprogrammable, and multipurpose [machine]”) which perform tasks like welding, painting, assembling, handling materials, or packaging. Thus machines that “have a unique purpose, cannot be reprogrammed to perform other tasks, and/or require a human operator” do not fall in this definition of industrial robots.

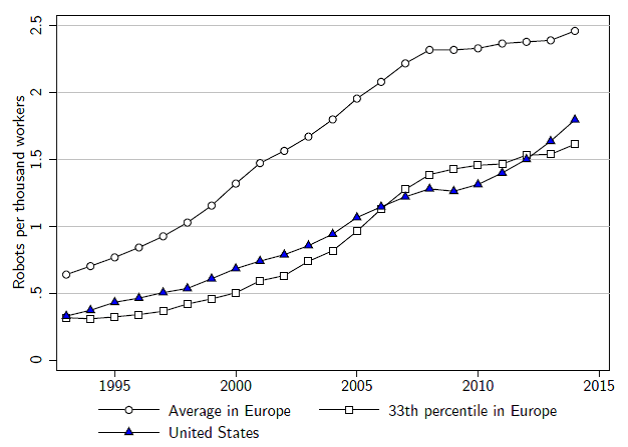

Using data from the International Federation of Robotics about industrial robots in the post-1990 era, the authors report that Europe has introduced more robots in its labour market than the US. In European countries, robot usage started near 0.6 robots per thousand workers in the early 1990s and increased rapidly to 2.6 robots per thousand workers in the late 2000s. In the US, robot usage is lower but follows a similar trend; it started near 0.4 robots per thousand workers in the early 1990s and increased rapidly to 1.4 robots per thousand workers in the late 2000s. In fact, the US trends are closely mirrored by the 35th percentile of robot usage among the European countries.

Source: Acemoglu and Restrepo (2017)

The authors conclude that one additional robot per thousand workers reduces the US employment-to-population ratio by about 0.18-0.34% and wages by 0.25-0.5%. The industry most affected by automation is manufacturing. However, interestingly, they only find a weak correlation between the increase of industrial robots and the decline of routine jobs.

When we are trying to interpret these results we should not forget that there are still few industrial robots in the US economy. If the spread of robots proceeds over the next two decades as expected by experts, such as Brynjolfsson and McAfee (2012) and Ford (2015), its aggregate implications for employment will be much larger. These books also warn that “white collar” jobs could be impacted just as much as “blue collar” ones.

Frey and Osborne (2013) predict that about 47% of total US employment is vulnerable to automation over the next 20 years. In contrast to the books mentioned above, the authors of this study also suggest that new advances in technology will primarily damage low-skill, low-wage workers as tasks previously hard to computerise in the service sector become vulnerable to technological advance. Bowles (2014) repeated Frey and Osborne’s empirical exercise for Europe, concluding that 54% of European jobs are at risk because of automation.

Chui, Manyika and Miremadi (2015) estimate that 45% of work activities could be automated using already demonstrated technology. If AI systems were to reach the median level of human performance, an additional 13% of work activities in the US economy could be automated. The study also finds that even the highest-paid occupations in the economy, such as financial managers, physicians, and senior executives, including CEOs, have a significant amount of activity that can be automated.

There are also studies that find a much smaller displacement effect of automation on employment. Arntz, Gregory and Zierahn (2016) predict that on average across the 21 OECD countries, only 9% of jobs are automatable. Atkinson (2016) agrees with this estimate, looking at the next 20 years, as he said at a recent Bruegel event about AI.

The big difference between this 9% estimate and 47% reported by Frey and Osborne (2013) is explained as follows: Frey and Osborne focus on whole occupations rather than single job-tasks (occupation based approach) when they estimate the risk of automation. Even if some occupations are labeled as high-risk occupations, they may still contain a substantial share of tasks that are hard to automate. In contrast, Arntz, Gregory and Zierahn adopt a task-based approach which focuses on the risk of specific tasks to be automated . That dramatically reduces the estimated impact of automation.

This makes clear that a crucial point when assessing the impact of automation is to determine what will be technologically feasible in the next decades and how capable the machines will be in replacing humans in their job tasks. Manyika et al (2017) estimate that only a fraction of less than 5% of tasks consist of activities that are 100% automatable, suggesting that a task-based approach can better capture the impact of automation. They also report that about 60% of occupations have at least 30% of their activities that are automatable.

All these studies have focused on the displacement effect of automation. What is even more challenging is to try to also assess the impact of the productivity effect. That would require predicting future market developments based on exact assumptions about the creation of new occupations, industries and tasks facilitated by new technologies that have not yet arrived. This is extremely hard to do! Who would have thought 20 years ago that with smartphones we would be able to perform many different tasks on one device, and that there would be huge new markets related to their function?

Even industry experts seem to be divided over the impact of automation on employment. Smith and Anderson (2014) asked 1900 experts in the field about the impact of AI on employment by 2025. Half (48%) envision a future in which robots and digital agents will have displaced significant numbers of both blue- and white-collar workers—with many expressing concern that this will lead to vast increases in income inequality, masses of people who are effectively unemployable, and breakdowns in social order. The other half of (52%) expects that technology will not displace more jobs than it creates by 2025.

There are also voices which claim that automation will not have any impact. Bob Gordon, for example, trying to explain mediocre US productivity growth concludes that “the benefits of the digital revolution were over by 2005” and that AI will only have a very limited impact. On the other side, the world-famous physicist Stephen Hawking goes several steps further by predicting that “the development of full artificial intelligence could spell the end of the human race.” The debate is broad, to say the least.

The fact that it is difficult to predict the exact impact of AI makes it complex to frame a policy response. But some society-level reaction is surely needed. It is therefore necessary to initiate an open consultation of all involved parties, to define our approach towards the AI era. This process will have several steps.

- The first important step is to understand what AI is and what its potential will be.

- Then, we need to define a framework of rules for the operation of machines and AI automated systems. These must go far beyond Asimov’s famous three laws of robotics. The Civil Law Rules on Robotics proposed by the European Parliament can also motivate social dialogue about issues related to liability, safety, security and privacy in the coming AI era. Adopting clear rules based on a good understanding of this new era could make the transition easier and mitigate potential concerns. However, adopting rules without good understanding and knowledge of how this new technology will be implemented (first step) would be be counterproductive.

- As a third step we need to design and implement those policies that will help us to accommodate new technology possibilities. For example, one way to move forward could be to carefully redesign education and training programs so that they provide the right qualifications for workers to interact and work efficiently alongside machines. This might minimise potential displacement concerns. Such initiatives will require the close interaction of authorities and institutions with major technological firms which have both the know-how and the capacity to contribute to the training. Improved instruments for job search assistance and job reallocation could also be beneficial and would mitigate concerns associated to the displacement effect. Without any doubt the Partnership on AI of the big high-tech companies can help promote the needed social dialogue and coordinate further developments with the participation of multicultural research groups and educational institutions.

At the moment we are far from a political consensus about the challenges of the AI era. The US Treasury Secretary Steve Munchin does not seem concerned at all about the impact of automation on employment. This position clearly contradicts the previous US administration, which even published a comprehensive report about the challenges of the AI era (considering employment one of the main worries). Christine Lagarde, in her talk at the Bruegel/IMF event shortly ahead of the 2017 IMF Spring Meetings, identified the impact of automation on employment as a concern that requires policy actions.

However, we should not rush into a response. The time for policy will come, but at the moment we are still at the first step of understanding the potential of AI and that various ways is might impact on our economy. To deepen this understanding, we should further promote social dialogue among all the involved parties (researchers, policy makers, industry representatives, politicians, etc). This is a vital first step to better grasp the challenges and opportunities of this new industrial revolution. And although we should not rush to conclusions, we must also act swiftly. The speed with which technology advances may introduce disruptive forces in the market earlier than some people might think.