Building positive incentives: the potential of coalitions for sustainable finance

We need to move towards more sustainable, long-term thinking in the corporate and financial worlds. Coalitions of willing actors could play a role in

This blog summarises the arguments of a recent essay by the author:

Investing for the common good: a sustainable finance framework

Introduction

In 2015, the United Nations developed the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, setting 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) intended to stimulate action over the 2015-2030 period within the economic, social and environmental domains. However, achieving these goals in the corporate sphere is challenging. Companies and investors typically do not take account of social and environmental externalities in their decision making. The problem is further aggravated by the short timeframes that executives and investors work in, since most of these externalities play out in the medium-to-long term.

As we work towards the UN SDGs, finance can play a central role because a key function of the finance sector is to allocate funding. A change of method and mentality would make it possible to prioritise funding for the most sustainable projects and companies, strategically analysing trade-offs and pricing risk. In a new essay, Dirk Schoenmaker provides a framework for sustainable finance describing a series of steps that could take the sector from a shareholder model to a stakeholder one, ultimately aiming to maximise the common good. The main issue is to align incentives, such as how to deal with short-termism. In this blogpost, we discuss the possible role of coalitions as a concrete way to drive this transition.

Coalitions for sustainable finance

When markets fail and incentives are misaligned, one typical solution is regulation and taxation. However, this approach does not always work, as we have seen in the international efforts to limit carbon emissions. Indeed, what brought countries together to sign the Paris Agreement (UNFCC, 2015) has been the voluntary nature of national climate pledges.

The Paris Agreement is an example of a coalition of interested parties – in this case at the country level – who work together to govern shared resources. Such coalitions are created without the intervention of centralised regulation and their members spontaneously develop rules to govern the use of the common good in question, to monitor members’ behaviour, to apply graduated sanctions for rule violators, and to provide accessible means for dispute resolution. In sum, the essence of a coalition is that membership is voluntary, but members must follow internal rules.

In practice, coalitions for sustainable finance and business have already emerged. Examples include the Principles for Responsible Investment (PRI), Focusing Capital on the Long Term Global (FCLT Global), the Global Impact Investing Network (GINN), the Equator Principles and the Global Alliance for Banking on Values (GABV). Among corporates, the World Economic Forum and the World Business Council for Sustainable Development (WBCSD) stand out.

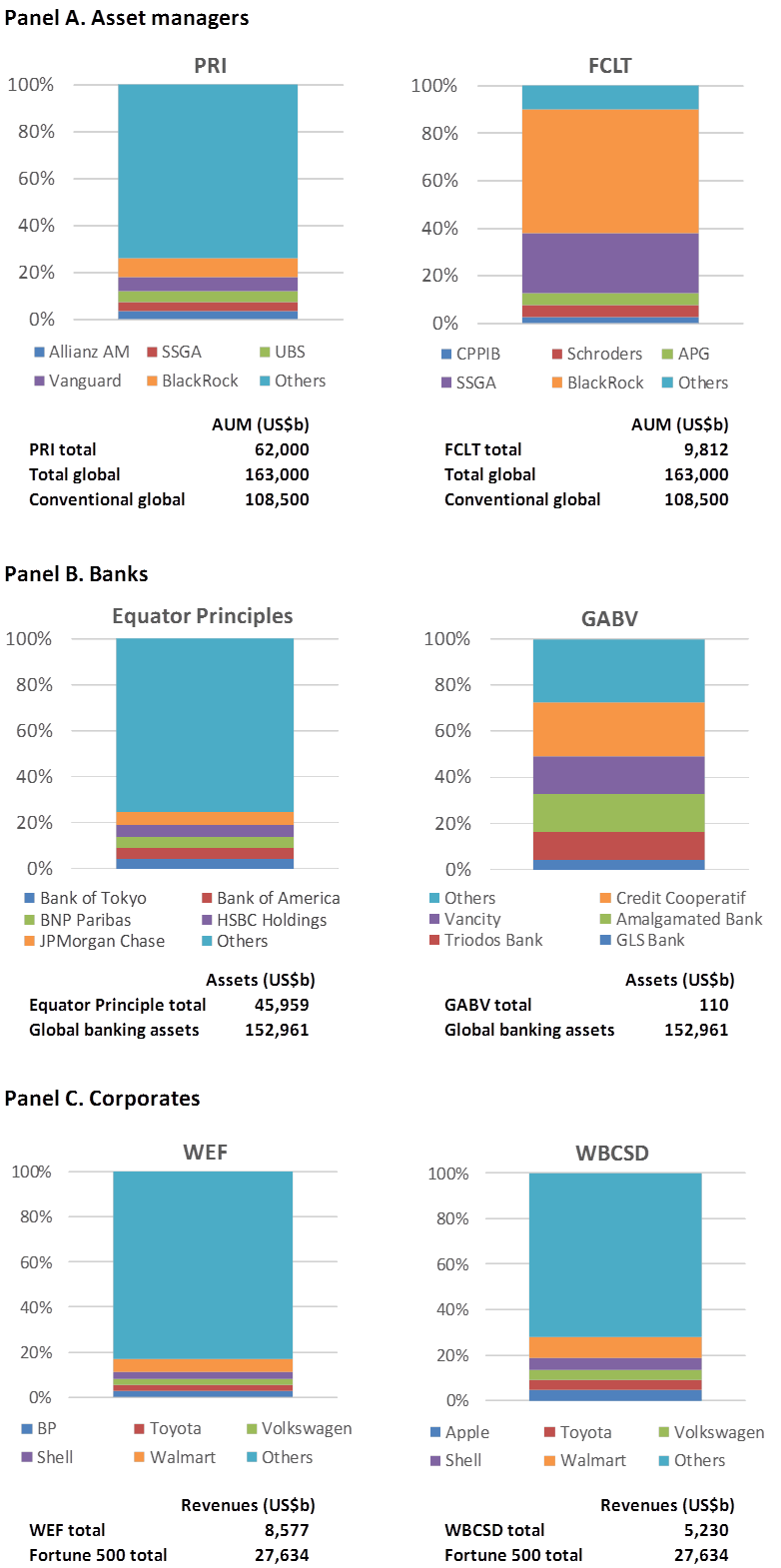

Figure 1: Coalitions for sustainable finance

Source and notes: see Table 1 and Appendix below.

Figure 1 describes the two main coalitions for asset managers, banks and corporates, by outlining their total size, main members and size of the reference group they belong to (respectively, global assets under management, global banking assets and Fortune 500 total revenues). Some of the coalitions are very small in comparison to their benchmark, with a few members making up most of the coalition’s total size (for example FCTL or GABV). Others are very big, with the five biggest members representing less than 30% of the total (for example PRI, Equator Principles, WEF).

This overview shows that the coalition members are drawn from North America, Europe and Asia. These coalitions thus have the potential to become a global force for the move towards sustainable finance.

But why would a bank or firm join a coalition? The simple answer is that focusing on short-term profits will eventually not pay off, while being intrinsically – or even just instrumentally – motivated to work on long-term value creation does. Remember, the long-term focus of these coalitions usually includes avoiding environmental and social hazards, which materialise over the medium to long term. These issues are harder to capture in a traditional short-term profit-maximising approach to finance.

However, all organisations – especially large ones – are complex. There are various complementary reasons why any given organisation might decide to join a coalition.

- Peer effect: the size of the coalition and the membership of key competitors push other peers to join in order to avoid a competitive disadvantage in the long term. Broad sectoral coverage also allows coalition members to implement changes that might otherwise bring competitive disadvantage in the short term.

- Outside pressure: consumers, NGOs and other associations can create incentives for an organisation to align its Corporate Social Responsibility principles to those of the coalition.

- Reputation: an organisation may want to join a coalition to be identified as a leader in sustainable practices or just to improve the perception of its corporate identity – in some cases it may become an actual marketing operation.

- Investment opportunities: a firm might be incentivised to join in order to avoid the risk of stranded assets, for example by grasping the opportunities offered by low-carbon investment which pay off in the long term.

- Collective advocacy: a coalition is stronger than individual entities in pushing governments to clarify their agendas and lobby for sustainable change. This can help coalition members reduce policy-related uncertainty over the future value of assets.

How to make coalitions work

Even if a new coalition has a clear joint mission or ideology, , many issues and undesirable incentives can arise. This can lead the coalition to self-destruct or underperform. The most obvious risk is free riding, whereby an organisation enjoys (part of) the benefits of a coalition’s membership without observing its principles and rules.

The pioneering work of Ostrom (1990) on the design of institutions for governing common resources can be applied in this context to understand what principles should be followed by a coalition for a proper and effective functioning. In order to make an initial assessment of the main coalitions for sustainable finance and business, we follow the design principles developed by Ostrom. Thus we assess each coalition on the following features:

- Clearly defined boundaries. Which percentage of the relevant sector is covered by the coalition?

- Membership rules restricting the use of the common good. How ambitious is the vision of sustainable finance that the coalition applies?”(Scores range from 1.0 to 3.0 with 3.0 being the most advanced - see this blog for a full explanation of this typology.)

- Collective choice arrangements. Can individuals or organisations affected by the coalition’s operational rules and principles participate in the modification of these rules and principles?

- Monitoring. Is there effective reporting on progress towards meeting the rules and principles, with assessment of the extent to which the rules and principles are followed?

- Sanctions and rewards. How are violations of coalition rules and principles punished; and how is compliance rewarded?

- Conflict resolution mechanism. Do coalition members and their officials have rapid access to low-cost local arenas to resolve conflicts between members or between members and officials?

Table 1: Coalitions for sustainable finance

As we see, there is clearly an inverse relationship between the quality of the sustainable finance typology and the size of the coalition. Table 1 shows that the larger coalitions – covering 20 to 40 per cent of the relevant reference group – sit somewhere between sustainable finance 1.0 and 2.0. These coalitions thus include social and environmental factors in their decision-making, at most alongside the financial factor, but do not give priority to them over profits.

However, it is interesting to note that coalition members tend to progressively tighten the coalition principles in subsequent versions, providing a dynamic component – some sort of virtuous cycle. However, not all coalitions even have clear principles guiding the behaviour of their members. PRI and WBCSD have well-defined sustainability principles, which are monitored and are also closer to sustainable finance 2.0 than the other coalitions (FCLT Global, the Equator Principles and WEF).

Conversely, coalitions adopting sustainable finance 3.0 put social and environmental factors first, with financial factors as a viability constraint. The coverage of these advanced coalitions is very small with less than 1 per cent of the relevant group covered. We classify GABV between sustainable finance 2.0 and 3.0, because as GABV stresses the triple bottom line (2.0) – people, planet and profit – as well as social and environmental challenges (3.0).

A key question for the effectiveness of these coalitions is the monitoring of the coalition members. Here the picture is very diverse. Some coalitions leave monitoring and reporting explicitly to the members (such as the Equator Principles Association), while the WBCSD explicitly reviews and benchmarks its members’ annual sustainability reports. Organisations need to map their whole scope tree and monitor not only their direct impact on society and environment, but also that of their clients and of the full value chain.

Reporting is a powerful mechanism that brings incentives for concrete action, often even without the threat of sanctions. However, the latter are even more effective and some coalitions do have a sanction-reward system in place. But this is often to a limited extent (for example, only for the board). The WBCSD instead threatens to expel members that do not meet the ‘membership conditions’ and is the only coalition with a conflict-resolution mechanism. The lack of a system that ensures enforceability is a clear weak spot of many coalitions.

Conclusion

Coalitions for sustainable finance and business make it possible to align incentives among different actors. Their role should be conceived in parallel with regulatory initiatives to address social and environmental externalities of corporate and financial activity. Private and public initiatives can thus reinforce each other. Private action can pave the way for public rules and taxes. In turn, public endorsement should strengthen private coalitions.

As short-termism is one of the main barriers to sustainable finance, we recommend that coalitions should adopt a long-term focus and take the time for new solutions to develop and flourish without quarterly benchmarking. Their members should engage with, and exert influence on, each other as well as the companies in which they invest and other stakeholders.

The features of coalitions that we analysed are crucial for a transition to sustainable development: coalitions should grow in size, to combine and reinforce individual efforts, and in scope, by stepping up the ambition of their model of sustainable finance. In order to function well, coalitions should adopt all the aforementioned design principles, particularly a proper enforcement mechanism. This will create the right incentives, avoiding preferential treatment and gaining credibility from the larger public.

Appendix