Ten years after the crisis: The West’s failure pushing China towards state capitalism

When considering China’s renewed state capitalism, we should be mindful of the damage done by the 2008 financial crisis to the world's perception of W

This article was first published by Le Soir.

The 2008 financial crisis radically changed the world’s image of Western capitalism for the worse. Apart from the massive cost of rescue packages offered to financial institutions in the US and Europe and the severe recession that followed, something even more important was lost due to the crisis – namely, the trust in capitalism as an economic model.

Following Lehman’s default, a drastic collapse in confidence spread like fire from one country to another. Investors lost confidence in the value of their assets to the point of not even relying on the ability of central banks to maintain financial stability. Against that background, two takeaways are worth mentioning. The first relates to the unintentional consequences of the crisis for Western democracies. The second focuses on how the collapse of the West’s faith in capitalism has negatively influenced China’s opening-up.

As for Western economies, they clearly opted for treating the symptoms rather than the disease that caused such a major crisis. In the US, astronomic funds were injected into financial institutions, while in Europe bank and sovereign rescue packages were needed. In addition, monetary and fiscal policies were used to save Western economies in a manner similar to that seen during the Great Depression.

The most significant inadvertent consequence of such pain-killing practices has been the transfer of private debt to the public sector. The increasing global burden of public debt will surely suppress growth in the future. As if that were not enough, the quantitative easing implemented by the US Federal Reserve and the European Central Bank created the conditions for a new asset bubble, both on fixed-income and equity spaces in the US and Europe, which has only further skewed income distribution towards the wealthy. Furthermore, the massive build-up of central-bank balance sheets is bound to limit the effectiveness of monetary policy down the road.

The “painkillers” proved insufficient to cure the entrenched problems of Western economies, which is reflected in the persistently low productivity of Western economies. This is especially the case for Europe and Japan. The structural reforms needed to increase labour productivity have not been carried out; policymakers prefer to exploit voters’ tendency to focus on their own short-term welfare, rather than the medium run or the prospects of future generations.

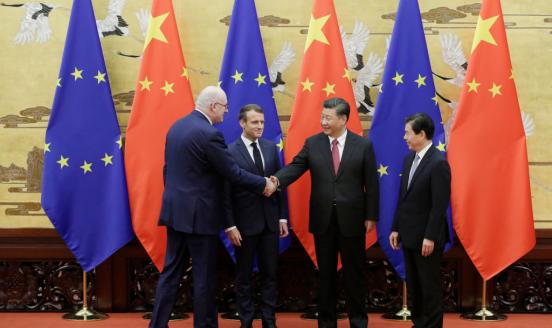

The second takeaway, perhaps less obvious but equally important, is the impact of the demise of the Western economic model on China. The global financial crisis has prompted Chinese authorities’ reassessment of the country’s economic goals and, more specifically, the type of economic model they may want to pursue.

In fact, China’s reaction to the global financial crisis has been to rely even more on state capitalism, instead of moving further towards a market economy. State-owned companies came to the rescue in 2008 to ensure that China kept growing and, most importantly, maintained employment as global trade was collapsing. The failure of many small- and medium-sized companies in China at the time was the trigger for state production to take over, supplemented by a massive stimulus package.

Apart from domestic political reasons for this move, the reality is that the global crisis unveiled a much darker face of the Western economic model, which led China to rethink its opening-up process. In other words, capitalism – and, thereby, private ownership of production – no longer looked as appealing after the global financial crisis, while state-ownership was instrumental for China’s insulation from the financial crisis.

Today, when looking at China’s renewed state capitalism, the West tends to blame China for not having stood up to the promises made when entering the World Trade Organization. But the reality is that our economic model has proven to be less of a model for China than we made it out to be. Before blaming China for diverging from our economic model, we should be mindful of our contribution to its decision-making process.