First glance

Assessing the Ecofin compromise on fiscal rules reform

The compromise reached by the Ecofin Council is imperfect. But it is still a big step forward.

On 20 December, the European Union’s Economic and Financial (Ecofin) Council reached a compromise on the reform of the EU fiscal rules. It represents a reasonable outcome. In some respects, it improves on the European Commission’s legislative proposal in April 2023. In other respects, it is worse. Compared to the current rules, however, it is a big step forward.

The Good:

- The country-specific nature of fiscal adjustment requirements, determined by debt sustainability analysis (DSA), is mostly preserved. This was the core idea of the European Commission. It will make implementation more likely.

- The use of a net expenditure path (expenditure net of interest payments and cyclical items) as the main operational target and the general and national escape clauses proposed by the Commission are also preserved. This will make the system less procyclical.

- While the Commission will run the DSA, the latter must be Council approved, published and replicable. This will increase collective ownership over the new methods.

- Some flaws in the Commission proposal have been fixed. The ‘debt safeguard’ that requires a minimum speed of debt reduction regardless of what the DSA says has been reformulated. The most important change is that the period over which the debt reduction is assessed only starts after countries have reduced their deficits below 3%. This gives high-deficit countries a chance to comply with the safeguard.

- The current Recovery and Resilience Programmes (RRP), which expire in 2026, will not be enough for countries to qualify for an extension of the adjustment period from four to seven years. EU countries will also be required to continue the reform efforts and nationally financed investment levels over the remainder of the four to five year period covered by their medium-term fiscal-structural plan. This generates good incentives.

- The independent European Fiscal Board is given a meaningful role in monitoring the implementation of the new rules.

The Bad:

- The Ecofin has agreed on a new ‘deficit resilience safeguard’ which requires countries to continue fiscal adjustment until they reach ‘a common resilience margin’ of 1.5% of GDP below the 3% deficit benchmark. The idea of requiring a ‘safety margin’ is not wrong. However, the safeguard micromanages the adjustment process (a minimum of 0.25—0.4% of GDP per annum) and the margin of 1.5% may prove too tough for some countries. In Italy’s case, the margin translates into a structural primary balance requirement of over 4% of GDP.

- The Ecofin seems to have reached a half-baked compromise on the implementation of the excessive deficit procedure (EDP). The annual minimum adjustment steps of 0.5% of GDP may initially exclude interest payments. However, the adjustment steps must include the interest payments after 2027. This will make life easier for the governments that negotiated the compromise, but harder for their successors, without any gain. For reasons explained in a previous piece, it makes little sense to measure these adjustment requirements in a way that includes interest payment.

- The financing of Council-endorsed public investment—particularly climate-related investment—should have been excluded from the application of the safeguards (while remaining included in the DSA). Instead, there is only a limited exclusion for RRP projects and national co-financing of EU funds in 2025 and 2026. Short-term fixes were given priority over politically more difficult but long-lasting reform.

- The role of national independent fiscal institutions (IFIs) has been grossly weakened compared to the Commission’s proposal. While the Commission proposal required IFIs to assess national compliance with the net expenditure path agreed with the Council, the Council’s version merely states that national governments ‘may request’ such an assessment. While EU governments are happy to have the European Fiscal Board monitor the Commission’s actions, they are clearly not happy to have their national fiscal board review theirs.

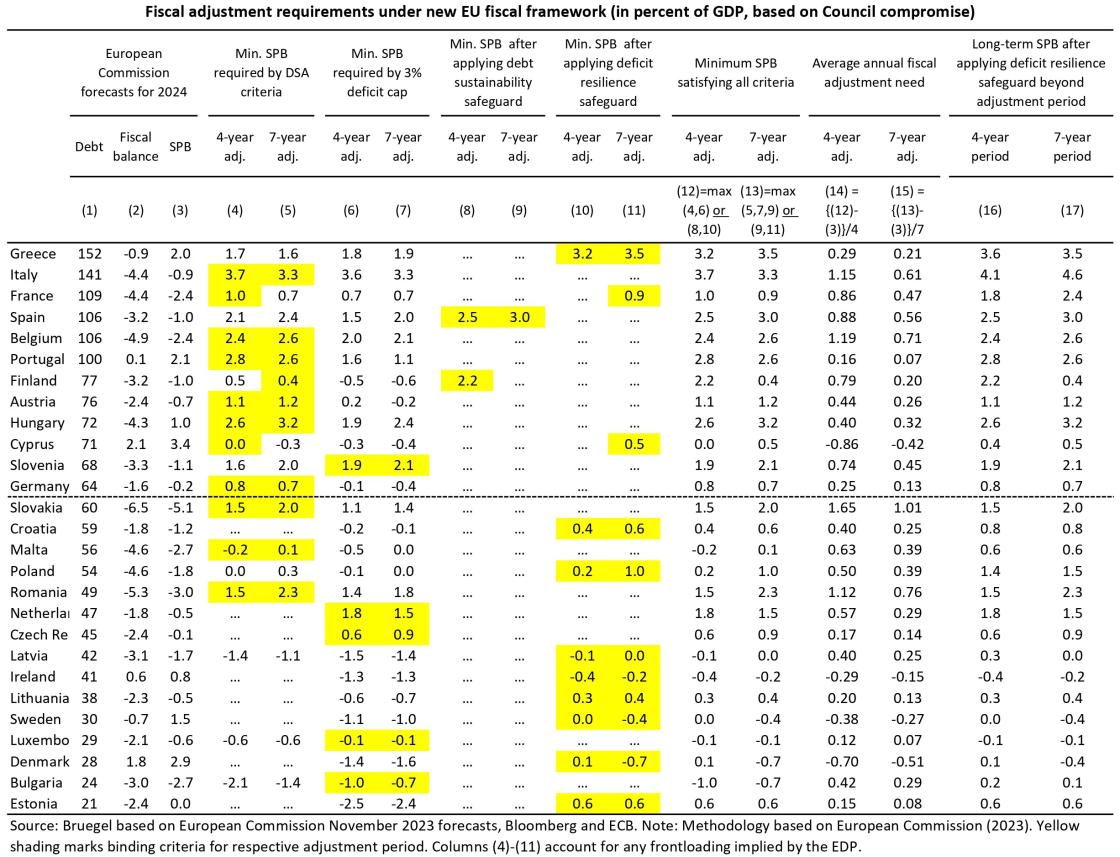

In the below table, there is an assessment of the fiscal adjustment consequences of the deal by Zsolt Darvas, Lennard Welslau and me (to the best of our knowledge). The methodology is explained here