Blogs review: output gaps and the behavior of inflation

What’s at stake: The big issue underlying most macroeconomic discussions these days is the extent to which the decline in GDP is temporary or permanen

Framing the issue

In his recently updated open-book on fluctuations, David Romer outlines that the United States entered into a prolonged period of below-normal output in 2008 and the unemployment rate has been over 7 percent for more than 3 years. Nonetheless, inflation has not fallen sharply. Excluding the effects of food and energy prices, which are volatile in the short run, it fell from around 2.5 percent in 2008 to between 1.5 and 2 percent in 2009 and has remained around that level. From the perspective of traditional models, this behavior is puzzling.

Greg Ip argues that three puzzles in the economic data – sluggish GDP growth, relatively rapid declines in unemployment, and stubborn core inflation – all make sense if the level and growth of potential output are lower than we thought. The failures of the 1930s and 1970s demonstrate that the stakes are high. If potential really is lower, it has disturbing implications for policymakers and investors: it means the structural component of today’s budget deficits are larger than believed and the Fed has less room to keep interest rates at zero.

Downward nominal wage rigidity

Ryan Avent argues that the literature suggests that we should not expect accelerating disinflation in the presence of large output gaps. This is not based on an ex-post assessment that expectations are well anchored but on the ex-ante observation that wages and prices display substantial downward nominal rigidity. In a recent IMF working paper, Andre Meier studies inflation dynamics during 25 historical episodes in advanced economies where output remained well below potential for an extended period and finds that such episodes generally brought about significant disinflation and slowing wage growth. But disinflation has tended to taper off at very low positive inflation rates.

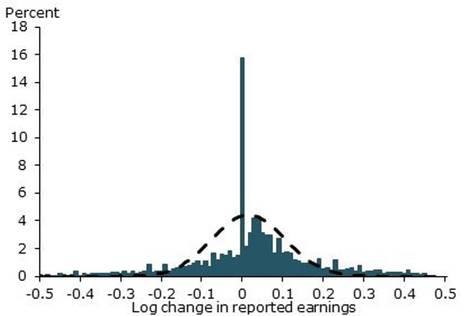

Mary Daly, Bart Hobijn, and Brian Lucking of the San Francisco Fed show in a recent paper – based on individual-level data from 1980 through 2011 from the Current Population Survey (CPS), the monthly survey conducted by the Bureau of Labor Statistics used to measure the unemployment rate – that many workers are getting precisely zero wage growth in dollar terms (see figure). Real wage growth, that is, wage growth after accounting for inflation, has held up surprisingly well in the recent recession and recovery. Despite modest economic growth and persistently high unemployment, real wage growth has averaged 1.1% since 2008. One reason real wage growth has been so solid is that inflation has been low, with the personal consumption expenditures price index increasing at an average annual rate of 1.8% since the start of 2008. Low inflation means that employers cannot reduce real wages simply by letting inflation erode the value of worker pay. Instead, if they want to reduce real labor costs, they must cut the actual dollar value of wages. But employers generally avoid doing so. During the recent recession and recovery, the run-up in the fraction of workers subject to downward nominal wage rigidity has been especially large. From 2007 to the end of 2011, the fraction of workers experiencing no yearly wage change rose to 16% from 11.2%. This is five percentage points higher than the average size of the spike at zero from 1983 to 2007, and higher than in any period in our sample.

Paul Krugman writes that the prevalence of zero-change wages constitutes overwhelming evidence that we’re suffering from lack of demand, not lack of supply. It also undercuts one of the favorite arguments of those claiming that we really do have a supply-side problem, the persistence of (low) inflation and positive wage growth despite the low level of employment. The reason we have positive wage growth is that workers with a good bargaining position are still managing to eke out increases, while those without aren’t facing wage cuts.

Anchored inflation expectations or the near-exogeneity of inflation

David Romer argues that the leading candidate resolution of this puzzle is based on the importance of anchored inflation expectations (or as Robert Hall put it in his presentation at the AEA earlier this year “the near-exogeneity of inflation in today’s economy”). What we are saying is that the rate of change of inflation depends on two factors: the departure of output from normal, and the departure of inflation from the central bank’s target. It seems unlikely that such a situation can continue indefinitely, however. The reason that the inflation target influences the behavior of inflation is that firms believe that the central bank will return inflation to its targeted level. If output is persistently below normal and inflation is consistently less than the targeted level, those beliefs are being repeatedly proven wrong. Thus at some point, firms would likely abandon those beliefs. When that happened, the usual dynamics of inflation would take over, and so the below-normal output would cause inflation to start to fall. An important question about the United States going forward from 2011 is how long output can remain less than its natural rate before that happens.

Temporary vs. permanent declines in potential output

Mark Thoma points that one of the puzzles in the macroeconomic literature about business cycles is that prices don't move anywhere near as much as a gap analysis implies they should. But the gap used in this analysis of often the distance between long-run potential output and actual output (i.e. the difference between the dotted line and the solid black line in figure 1 or figure 3). But if price pressure depends upon the gap between short-run capacity and actual output and if output and short-run capacity co-vary positively after a shock, then the gap and hence prices could be relatively constant throughout the cycle.

Mark Thoma notes, however, that policy makers should not focus too intensely on short-run potential output because capacity will grow as the economy recovers. In other words, don't confuse a temporary decline in potential with a permanent decline. The point is that there can be short-run cyclical AS effects, and failing to account for these can lead to policy errors. I believe many people are treating what is ultimately a temporary fall in capacity as a permanent change, and they are making the wrong policy recommendations as a result. In fact, there's no reason to think productive capacity can't return to its long-run trend just as fast or faster than output can recover. For example, when there as a large AD shock in the form of a change in preferences, say that people no longer like good A as it has gone out of fashion and have now decided B is the must have good, then there will be high unemployment in industry A and excess demand for labor and other resources in industry B. As workers and resources leave industry A, our productive capacity falls and it stays lower until the workers and other resources eventually find their way into industry B. When this process is complete, productive capacity returns to where it was before, or perhaps goes even higher. Thus, there is a short-run cycle in productive capacity that mirrors the business cycle.

Europeans can’t blog

Karl Whelan complains that once more Europeans can’t blog as this important debate is taking place in the US, but not in Europe while the issue of calculating output gaps is particularly important given the Fiscal Compact (see our recent blogs review on the topic). If anything the issues are more complex given the variety of different structural issues facing European economies. For example, in 2007, the Commission estimated that Ireland’s output was 0.2 percent below its potential level. Now, with the benefit of hindsight, the Commission estimates that Ireland’s output was 3.7 percent above its potential level in 2007. Interestingly, the Commission is projecting the Irish output gap to have disappeared by next year, despite an unemployment rate of 13.6 percent. We have yet to find out which body will be charged with calculating Ireland’s cyclically adjusted deficit by the fiscal responsibility bill required to implement the treaty. However, I doubt if they will agree with this particular aspect of the Commission’s analysis. Philip Lane has more details on what the “six pack” Council Directive implies on this issue.

I guess it might be time for Natacha and I to update our analysis on this issue or for Jean Pisani-Ferry and Adam Posen to do so.

*Bruegel Economic Blogs Review is an information service that surveys external blogs. It does not survey Bruegel’s own publications, nor does it include comments by Bruegel authors.