Blogs review: the UK’s output, employment and productivity puzzle

What’s at stake:While the decline in output in the UK over the last few years has been the longest and nearly deepest since the Great Depression, em

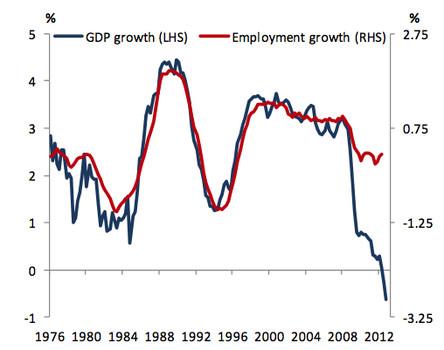

What’s at stake: While the decline in output in the UK over the last few years has been the longest and nearly deepest since the Great Depression, employment has remained surprisingly stable, even recently increasing at an impressive fast pace despite the double-dip recession. Contrary to the US, which has experienced recent increases in productivity, many European countries have seen persistently weak productivity. But the UK’s loss of labour productivity stands out, as it is now 10% below its pre-crisis trend. Whether the nature of this decline is temporary or permanent has become a central issue for policymakers in the UK.

A gravity defying labour market

The Economist’s Free Exchange ask why, to put it crudely, are we consistently having more jobs and less stuff being produced?

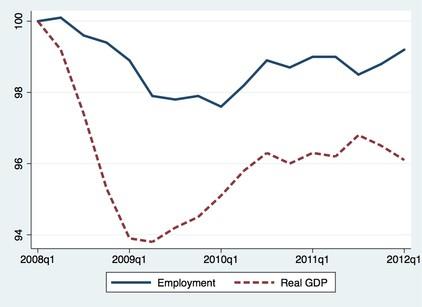

Joe Grice – chief economist of the Office for National Statistics – writes that the labour market has exhibited greater resilience than might have been expected from the outturns for GDP. Since the start of the recession at the beginning of 2008, employment has fallen by less than 1 per cent, and indeed has risen from its low point at the end of 2009. By contrast, GDP has fallen by approximately 4 per cent over the same period. While it also recovered somewhat from its low point in the middle of 2009 – when its cumulative decline exceeded 6 per cent, the subsequent recovery petered out.

|

|---|

| Source:Ben Broadbent |

|

| Source: Bruegel based on ONS data |

Ben Broadbent (HT Martin Wolf) – an external member of the MPC – writes that in more normal times, the 3% drop in output since mid-2007 would have been associated with an 8% decline in the number of jobs. Instead, and despite a contraction in the public sector, aggregate employment has risen slightly over the last five years. Broadbent also notes that what’s striking about the employment data is not so much the weakness of lay-offs but the strength of new hires. The private sector has created more new jobs in the past two years than in any two-year period (at least) since the data on gross flows began in 1997.

Chris Giles has become irritated by “the NIESR chart” – which shows that the current recession is the longest and nearly the deepest since the start of the 1930s based on GDP – because it is not a sufficient description of the UK’s recession. Everyone knows GDP is an imperfect measure, but it is often a useful summary of an economy when other things are moving in line with it. But in this recession they are not. Not even close. The equivalent chart to the NIESR chart for employment shows that the current downturn is competing with the 1970s equivalent to be the shortest and shallowest recession in post-war UK economic history (Jonathan Portes responds here to the attack).

Abigail Hughes and Jumana Saleheen – two economists at the BoE – show that, in the past, productivity has typically recovered back to its pre-crisis trend after about four years. This usually happened because the falls in output were eventually accompanied by falls in employment, rather than because output recovered. This time has been different. Many European countries have seen persistently weak productivity, often weaker than has typically been seen in previous crises. The UK stands out as having the weakest performance, with the current level of labour productivity being 10% below a simple pre-crisis trend. The falls in productivity in Germany, France and Italy in the recession were concentrated in manufacturing. Over the recovery, manufacturing productivity has grown faster in these countries than in the UK, which explains why they have started to reclaim some of their lost ground. In contrast to other countries, much of the sustained weakness in UK productivity is concentrated in services, where the level is still below its pre-crisis peak.

This unproductiveness is temporary

Simon Wren-Lewis writes that falls in labour productivity are what might be expected in a demand led recession, because it takes time for firms to adjust employment. However, after a while one of two things should happen. The first possibility is that employment adjustment does occur as firms reconcile themselves to lower output, so productivity should rebound. It has not, particularly in services. The second is that firms are hoarding labour because they think output will recover to something like pre-recession trends. But in that case they should be reporting substantial spare capacity, which we have seen they are not.

In a FT column published in May (HT Marginal Revolution), Martin Wolf summarizes the findings of a paper by the Centre for Business Research at the University of Cambridge: The hypothesis of the paper is that the combination of a general collapse in demand with incentives to hoard labour explain what has happened. If demand were to rebound, so would productivity. Bill Martin – one of the two authors of the paper – adds that both the US and UK economies appear to be primarily constrained by the weakness of demand, but with different modes of adjustment.

A recent survey of the Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development (HT Ian Brinkley) reports that almost a third of private sector firms have maintained staff levels higher than is required by their current level of output during the past year. The main reason for holding on to labour is to maintain the skills base within the organisation (as reported by 62% of these employers). Meanwhile, almost two thirds of private sector firms feel that they would be forced to cut back on labour if output or service delivery does not pick up in the next year.

Ian Brinkley – director of the Work Foundation – writes that, while labour hoarding is consistent with longer run changes that have seen the workforce becoming better educated and jobs becoming more knowledge intensive – changes that mean the costs of short-term “hire and fire” policies have risen –, the problem with the labour hoarding story is that it has been going on for several years – and it doesn’t really explain the rise in employment. This is a very job-rich recovery – far more so than in the first years of recovery from previous recessions.

Still based on the CBR paper, Martin Wolf writes that employment has mostly expanded for labour in low-productivity, low-wage activities, where hoarding did not occur. It has not expanded for high-productivity, high-wage labour. This then is a divided response in a dual labour market.

Andrew Sentance – senior economic adviser at PwC and former member of the MPC – writes on the PwC blog provides a list of UK specific factors that help explain why UK employment has performed better than in previous recessions. The first is a change in the structure of employment. In major UK recessions, around 90 per cent of the job reductions have occurred in two highly cyclical sectors of the economy – manufacturing and construction. These sectors now account for a smaller share of jobs, and so have generated less job losses this time around. A second factor has been the underlying health of the UK business sector. In the two earlier recessions, the loss of jobs was intensified by structural problems. By contrast, the non-financial business sector of the economy was in much better shape when the financial crisis hit, and companies were in a better position to retain skilled and experienced workers. The other two factors are wage flexibility and policy measures, which has resulted in subdued wage increases, more part-time jobs and self-employment growing strongly.

Technical regress, supply potential, and the misallocation of resources by an impaired financial system

Ben Broadbent writes the longer the divergences between output growth, employment growth and inflation go on, the harder it is to believe that there hasn’t also been a genuine hit to the economy’s effective supply capacity.

Ben Broadbent writes that there needn’t have been any “technical regress” for this to have occurred. A combination of uneven demand (across sectors) and an impaired financial system, one that is unable to reallocates capital resources sufficiently quickly to respond to such shocks, is enough to reduce aggregate output per employee. Such a process would also give rise to precisely the volatility in relative prices and the widening sectoral dispersion of profitability we’ve observed in the data. Some firms, it seems, are kept in business (and retain employees) despite making relatively low returns. Others, able to expand but unable to obtain the finance to do so, are forced to substitute labour for capital. It’s hard to imagine this dispersion in returns can persist indefinitely. Assuming the underlying shifts in relative demand are permanent, the economy must in the end adapt to them. Indeed, at some point, once the financial system returns to health, one could imagine exactly the reverse process: a long period of above-trend productivity growth. If this is true, the economy’s lost potential is the result of a misallocation of capital, rather than any form of “technical regress”. In that case it needn’t have been lost forever. In time, as the financial system heals, and investment starts to flow, the economy could well expand at an above-trend rate (without generating inflation), catching up some of the ground lost over recent years.

Real Time Economics writes that the central bank’s efforts to revive the economy now include trying to fix this logjam. The BOE has launched a funding for lending scheme that offers lenders cheap central bank money provided they use it to make new loans. Thirteen banks have signed up so far.