Blogs review: The US hitting the debt ceiling

What’s at stake: Despite indications of a possible deal between President Obama and the Republicans in the US Congress, there is still a risk that the

What’s at stake: Despite indications of a possible deal between President Obama and the Republicans in the US Congress, there is still a risk that the US Treasury hits the debt ceiling sometime after October 16th unless it is raised in time. A default on US government debt may result. Despite general optimism that a deal will be reached in time, discussion about what such a default would imply for financial markets and the global economy, as well as about creative solutions to the problem and the consequences of policy uncertainty abounds in the blogosphere.

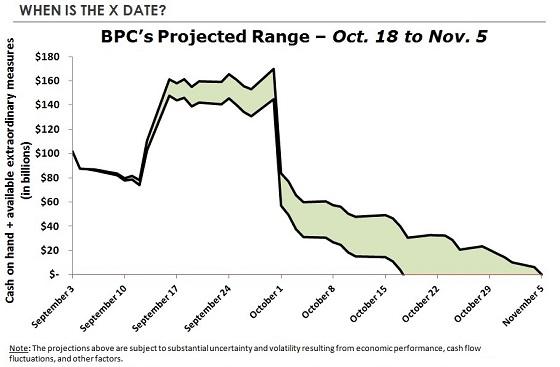

When is the x-Date? A forecast of cash-on-hand of the US Treasury if the debt ceiling is not raised.

Source: Washington Post / Wonkblog , Bipartisan Policy Centre.

Could default be avoided by prioritising expenditures?

Greg Ip explains that the US Treasury reached the current debt ceiling of $16.7 trillion on May 19th and has since used “extraordinary measures” to keep issuing bonds and bills. These extraordinary measures will be exhausted on October 17th, after which the government will have to default on some of its obligations. This does not necessarily mean defaulting on debt, if the government can prioritise the refinancing of maturing debt in its expenditures. However, if, due to some technical mistake, payments on debt are indeed missed, this would be unprecedented.

Mike Konczal inquired with leading conservative think-tanks what they make of the issue. The Heritage Foundation and Cato Institute essentially think that prioritisation of debt service over other expenditures is feasible, giving the President the choice whether to default or cut other spending. Michael Strain from AEI was less upbeat, cautioning that things can go wrong trying to prioritise expenditures. The experiences from 2008 and 2011 indicate that going through the debt ceiling would be a catastrophe.

Alec Phillips and Kris Dawsey of Goldman Sachs think a temporary default could occur as the Treasury will technically not be able to prioritise expenditures – its system that handles 4 million transactions per day is not set up to enable prioritisation. The effects of a temporary short-term default may be milder than expected by some (the Fed can keep accepting Treasury securities as collateral and a temporary downgrade may not necessitate fire sales by money market funds), but the real risk is that in a longer delay of several weeks, a fiscal tightening of up to 4.2% of GDP (annualised) would result, with harsh consequences for growth the longer the squeeze lasts.

The macro effects of a default

Barry Eichengreen writes that the Dollar has displayed remarkable resilience in being the world’s main reserve currency during previous crises, as investors piled into US government bonds because they offered liquidity and safety. But these are precisely the attributes that would be jeopardized by a default. Losing the status as global reserve currency could mean a loss of up to 2% of GDP for the US from increased borrowing costs – and also the loss of the insurance through a currency that automatically strengthens when something in the world goes wrong. The global consequences would include an unwelcomed strengthening of the Euro, just as the crisis countries struggle to regain competitiveness, and a sharp appreciation of small “safe” currencies. If even larger advanced economies would in the end be forced to implement capital controls, this would gravely endanger financial – and indeed economic – globalisation.

Tyler Cowen thinks that if by some freak chance, the ceiling is indeed not raised in time, the following story may play out: Before 17th October, information that not all is well will leak, interest rates skyrocket and liquidity in the T-Bills market becomes scarce. On the 17th some payments on Treasuries will be missed and eventually, the payments system shuts down, as even a flood of monetary liquidity can’t make up for the fact that T-bills no longer are a safe asset. When the problem is resolved– by issuing Super Premium Treasuries (see below) or lifting the ceiling – some major financial institutions will have become insolvent and have to be nationalised, uncertainty about the others’ solvency will abound. GDP will have dropped by 5-10% and borrowing costs increased permanently.

Turmoil in financial markets

Cited on FT Alphaville, Dick Bove describes an apocalyptic scenario of what a US default on Treasury securities would cause on financial markets. The US banking industry owns $1.85 trillion in government backed securities - $166 billion of Treasury securities and $1.68 trillion in agency guaranteed debt. In default, it is unclear how this would be valued. In a Latin American scenario of 10-20 cents on the dollar, $ 1.28 trillion of presently $1.63 trillion of Bank equity would be wiped out – before considering the loss in value of $7.73 in loans and $1.27 in securities. A true default by the United States Treasury would wipe out bank equity.

Kevin Roose sees three channels through which a default can cause havoc: Firstly, it may cause Fedwire, the Fed-run clearing system of US banks, to seize as that system is not designed to allow defaulted Treasury bonds to flow through it. Secondly, the Fed could no longer accept Treasury bonds as collateral for its borrowing window and thirdly, the repo market may freeze up as defaulted Treasury bonds would no longer be valid collateral.

Barry Eichengreen writes that, in the event of a US default, mutual funds that are prohibited by covenant from holding defaulted securities would have to dump their Treasuries in a self-destructive fire sale. Money-market mutual funds, virtually without exception, would “break the buck” (i.e. be unable to repay investors), allowing their shares to go to a discount.

FT Alphaville quotes a Fitch note saying that, under a “technical short term default”, money market mutual funds (MMFs) would not actually be required to sell of Treasury securities. Pressure on funds could rather originate from liquidity problems. As many MMFs rely on the UST-backed repo market and some government MMFs invest only in USTs, this can be a source of trouble for MMFs if investors decide to pull out money.

A lunatic idea that may work? Super-premium bonds

Matt Levine picks up on a crazy idea by Sonic Charmer to get around the debt ceiling – and it’s not the trillion dollar coin. The Treasury could issue bonds at a very high coupon rate such as 30%, which would be auctioned for much more than the face value. As the debt ceiling applies to the face amount of bonds, this is a way to keep the face amount of outstanding bonds below the ceiling while raising enough financing both for the rollover of maturing bonds as well as the current deficit. A 24.5% coupon on 10 year bonds or 18.75% on 30 year bonds would suffice. In the domain of lunatic schemes, this one “gives off less of a banana-republic-from-outer-space whiff than the platinum coin does”. And it has happened before – it was essentially the trick Greece pulled to reduce its official debt-to-GDP ratio to comply with EU treaties.

UBS’s Mike Schumacher and Boris Rjavinski, cited in FT Alphaville, add some considerations. They think the bond would find enough buyers in total return investors with short time horizons and pension funds. There would be some impact of this strategy on the yield curve as the unexpected dose of duration would lead to rising long rates, although Treasury can spread the impact across the yield curve. And, finally, they expect the cost of this scheme (due to liquidity premia on the super premium bonds) to be around $1-$1.5 billion per month, which makes the deal seem compelling compared to a US default.

Policy uncertainty, once again

A paper by the Department of the Treasury considers the effects of policy uncertainty during the last debt ceiling episode in summer 2011. Apart from a decline in consumer and business confidence indices, stock market prices fell significantly – the S&P 500 suffered a 17% decline (impliying a stunning $2.4 trillion drop in household wealth) and took about half a year to recover. Stock market volatility, corporate credit risk as well as mortgage spreads also rose. Renewed uncertainty will result in a slower economy with less hiring and a higher unemployment rate.

Simon Johnson points to research on policy uncertainty by Baker, Bloom and Davis, which finds that the debate about the debt ceiling in 2011 generated the highest level of policy uncertainty in the US for the past 25 years with clear, negative economic effects. The 2011 debate alone pushed up government borrowing costs and increased risk premiums around the world. Using the debt ceiling as a “forcing moment”, as the GOP does, is an irresponsible way to run fiscal policy as it will create uncertainty and adverse economic effects at the level of 2011 or even higher.

Annie Lowrey mentions that the cost of the 2011 debt ceiling uncertainty episode have been quantified as $1.3 billion for 2011 (US GAO) and $18.9 billion over 10 years (Bipartisan Policy Center).