Blogs review: Germany’s Energiewende

What’s at stake: Managing Germany’s highly ambitious plans for a transition to electricity generation from renewable sources will be a main task

What’s at stake: Managing Germany’s highly ambitious plans for a transition to electricity generation from renewable sources will be a main task of the incoming German government. The aims for the “Energiewende” in the new coalition agreement are for renewable energy to account for 40-45% of energy consumption in 2025 and 55-60% in 2035. A key challenge will be to implement a new market design in the electricity market that allows a cost-effective integration of energy from renewable sources, as the current subsidy scheme is coming under increased pressure, both from domestic consumers and companies for its costs and from the European Commission for its compatibility with state aid regulations.

The Energiewende so far – success or failure?

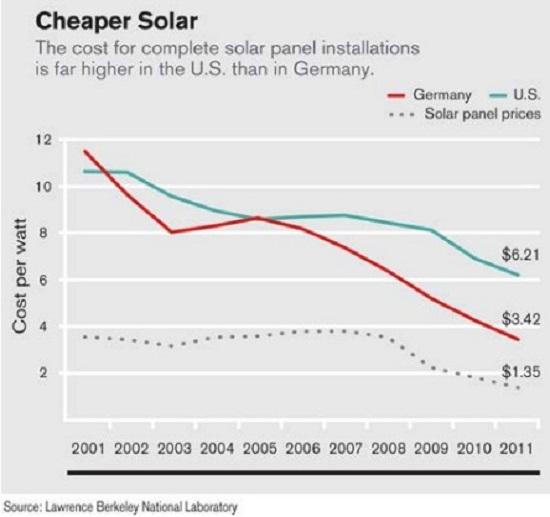

Hal Harvey argues that the Energiewende has so far achieved a crucial goal: Public support for renewable technologies has radically brought down the prices, particularly for wind and solar power installations. This, as any introduction of a major energy technology, required socialization of the costs of the early stages.

Source: Hal Harvey

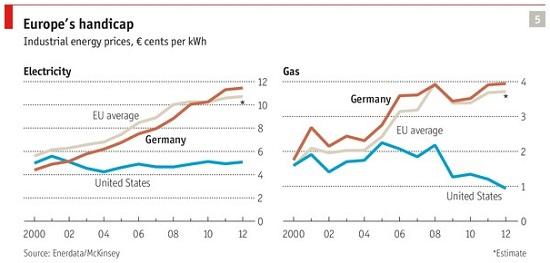

The Economist points out that there is an increasing cost problem in Germany: household electricity bills in Germany have risen to now be 40-50% above the EU average. And rising energy costs threaten to also become a competitive impediment to German firms as energy costs in other parts of the world are plunging, partly due to the “shale gas revolution”. At the same time, more renewable energy lowers the wholesale electricity price, driving out energy-friendly gas as source of necessary conventional back-up power and leading to a renaissance of dirty, but cheap coal power in German power generation

Source: The Economist

Mat Hope objects to the latter argument: The renaissance of coal power is caused by its relative competitiveness against natural gas, not by Germany’s policy on renewable energy. Gas is relatively expensive on international markets and the collapse in the EU’s carbon price during the economic crisis has benefited polluting technologies such as coal power.

Reform proposals for the EEG

The subsidy scheme is a key issue in the debate over the future of the German “Energiewende”. Georg Molz explains it here: Producers of renewable energy receive technology-specific, fixed feed-in tariffs (a price guarantee for 20 years with some inbuilt price decrease over time) for any electricity they produce at any time. The difference between these tariffs and the spot market price has to be paid by consumers through a surcharge on their electricity bill. Of the 18 billion Euro feed-in tariff payments in 2012, 5 billion were financed from selling the electricity on the spot market and the remaining 13 billion were paid through the surcharge. As increases of the surcharge have led to much criticism of the subsidy scheme, a number of studies consider how a build-up of renewable generation capacity can be incentivized more efficiently.

A paper by Agora Energiewende argues that the build-up of wind and solar power generation capacity - the most cost-efficient technologies available - will be the centerpiece of the Energiewende. Secondly, because both technologies have marginal costs near zero, they cannot be successfully operated on marginal-cost based electricity markets. Prices will converge to zero as more renewables enter the market. A future market will have to provide two revenue streams to energy producers: One from the sale of electricity and another from an “investment market” that rewards investments in flexible energy generation capacity or demand-side management capacity and generation capacity from renewable energy sources.

The German Academy of Science and Engineering argues that the EU’s Emissions Trading Scheme should be the centerpiece of any climate protection policy, potentially alleviating the need for separate subsidies for renewable power generation. As long as separate renewable energy goals are pursued, feed-in tariffs should be replaced by system in which subsidies are a fixed premium on top of wholesale market electricity prices. This will lead to investments into the right technologies at the right locations.

A study by Frontier Economics underlines that a technology-neutral subsidy scheme coupled with the requirement that producers sell their own energy on the energy exchange will lead to efficiency gains. The latter aspect will ensure that energy is only produced when it is efficient to do so (i.e. the market price exceeding the marginal costs of production). It will also incentivize the construction of renewable capacity at locations where generation is likely to occur at times of high market prices, implying less correlated renewable energy generation. This can be achieved through either a quota/auction system or a fixed market premium subsidy on top of wholesale market revenues.

Justus Haucap argues that technology-specific feed-in tariffs have led to an excess build-op of solar energy, although it is the most expensive technology in Germany. Cost decreases for solar panels created a solid profit margin under the pre-set, high feed-in tariffs for solar power, leading to a surge in solar panel installation. A technology-neutral quota system with tradable green energy certificates, obliging energy retailers to buy sufficient certificates to ensure the quota is met, would be an efficient alternative in which the cheapest available technologies would be utilised.

Peter Bofinger points out weaknesses of the quota system: It actually requires very strong assumptions. As revenues stem from a trade in “green energy certificates” that retailers must buy from suppliers, robust quantitative goals for the entire investment horizon of new plants are required so that expectations on revenue streams can be formed. This creates a huge scope for miscalculations on the sides of governments and investors, the cost of which will be passed on to consumers. Also, it will give rise to a market that favours large companies better able to shoulder risks, leading to less competition and higher prices. Instead of the quota model, auctioning subsidies for renewables up to pre-defined targets are a cheaper and less risky alternative.

Capacity Markets

The second main strand of the debate about the future of the Energiewende is, whether capacity payments are required to provide sufficient income for conventional back-up capacity that is required as a complement of fluctuating renewable energy sources. As conventional power plants work fewer and fewer hours when more renewable energy enters the system, a missing money problem arises in which the marginal back-up power plant that only works once per year no longer generates sufficient income for its owners to keep it online.

A study by Consentec concludes that a strategic reserve of power plants constitutes a minimal intervention in the power market that brings about sufficient safety that adequate generation capacity is available. Under this concept, owners of some power plants are paid to hold their plants available for electricity generation in times of scarcity, identified by high strike prices at which the reserve plants can spring into action. Below the strike prices, reserve plants will not participate in the market.

The energy institute of Cologne University argues that high peak prices for electricity – which in theory could ensure the financing of the marginal power plant – are unlikely to be allowed due to concerns about market power. Therefore, capacity payments will be required. A comprehensive capacity market in which the required safe generation capacity is determined and a corresponding number of contracts are auctioned should be preferred over a strategic reserve. Suppliers of safe power receive payments for holding their capacity available and participate normally in the market. This model will be more efficient as all power plants operate on the market and no payments are made for non-participation. Also, it restricts market power by including a maximum price, at which contract holders are obliged to utilize their generation capacity.

Claudia Kemfert et al. argue that a capacity market will not be required. At present, low wholesale market prices for energy are partly a consequence of existing excess generation capacity that will ensure supply security until at least 2023. In the long run, a market design focusing on the electricity wholesale market and a complementary strategic reserve will be preferable compared to capacity markets as it strengthens the role of the wholesale market in transmitting information and incentives. Also, the distributive consequences will be milder than those of a capacity market, in which a far higher number of actors receive capacity payments.

The contents of the new coalition treaty

Matthias Lang writes that the renewable energy goals in the coalition treaty are broadly in line with those currently in force. No major reforms of the subsidy scheme are planned in the short run, just a gradual reduction of feed-in tariffs for new plants to avoid excess payments. On the level of technologies, the targets for offshore windparks – which have proved to be far more expensive than expected – are reduced by about one third and existing curbs on the build-up of solar power shall remain in place. Notably, from 2017, new plants of 5MW or more will be obliged to sell their energy directly on the energy exchange, which implies a departure from the present subsidy scheme of fixed feed-in tariffs.

Benedict de Meulemeester writes that the major novelty in the coalition treaty on energy is the commitment to introduce an auctioning model for the renewables subsidies by 2018, preceded by a pilot project for 400 MW of solar capacity in 2014, which could herald a new way of subsidising renewable energy. Due to the vagueness of the treaty on most crucial issues, it will be important to keep a close watch on political developments as major decisions are yet to be taken.

The European Dimension

Charlemagne points out that there would be great advantages in integrating the EU electricity and gas markets. Not only that cost savings in the order of 65 billion Euros per year could be achieved through lower energy prices, better EU integration could greatly facilitate the transition to decarbonised energy generation. More cross-border interconnectors between national electricity grids would permit building windmills and solar panels where the best conditions exist and ensure a better absorption capacity of the grid for less correlated fluctuating energy sources. Done properly, an integrated energy market could favour the transition to renewable power, enhance security and promote cheaper energy.

Yet the European level also creates some troubles for the current German approach: The European Commission has just opened an in-depth investigation into whether the large number of exemptions for “energy intensive” companies from the renewables surcharge in Germany is compatible with EU state aid regulations.