Blogs review: GDP, welfare and the rise of data-driven activities

What’s at stake: The worry today is not that investment in technology might not be as productive as we thought (the so-called computer paradox),&

What’s at stake: The worry today is not that investment in technology might not be as productive as we thought (the so-called computer paradox), but the fact that the economic value of the fast growing consumption and production of online data may not be adequately captured in official statistics. While GDP has always been an imperfect metric for welfare, a number of authors have wondered if this issue has not become worse in the information age.

Cartoon by Manu

The GDP puzzle

Erik Brynjolfsson and Adam Saunders write that we see the influence of the information age everywhere, except in the GDP statistics. More people than ever are using Wikipedia, Facebook, Craigslist, Pandora, Hulu and Google. Thousands of new information goods and services are introduced each year. Yet, according to the official GDP statistics, the information sector (software, publishing, motion picture and sound recording, broadcasting, telecom, and information and data processing services) is about the same share of the economy as it was 25 years ago — about 4%.

Erik Brynjolfsson and Adam Saunders write that the answer isn’t about quantity, it’s about price. GDP is a measure of the current market value of production. So if you listen to a free song, there’s virtually no contribution to GDP (perhaps a few fractions of a cent for the electricity you use). Brynjolsson notes that you could have an enormous of explosion of bits or articles or whatever else. If they’re priced at zero, the statisticians in Washington do the math and, lo and behold, it comes out as a big fat zero contribution for our GDP.

Free goods, GDP and consumer surplus

Since most of the on-going discussions about free online services and data revolve around their ‘unrecorded’ value in GDP statistics, it is tempting to think that everything would be fine if only this ‘value’ could be included ‘back into’ GDP. But it misses the distinction between GDP and economic value. Since its invention as part of the development of national income and product accounts by the US and UK treasuries in the 1930s and 1940s GDP was and remains primarily designed to capture, in the words of Robert Costanza and co-authors, “only monetary transactions related to the production of goods and services”.

Greg Ip writes that typically economists determine non-monetary benefits by trying to calculate "consumer surplus": the difference between what a consumer pays and what they would be willing to pay. As stressed by Shane Greenstein, even for a good that has a price, it is hard to estimate consumer surplus. This issue is as old as newspapers and libraries as the benefits a reader obtained from a local newspaper probably exceeded the $0.25 he or she paid. Greg Ip notes that when so many Internet services such as search and social media are free and have no precise market based analog, the task is made even harder.

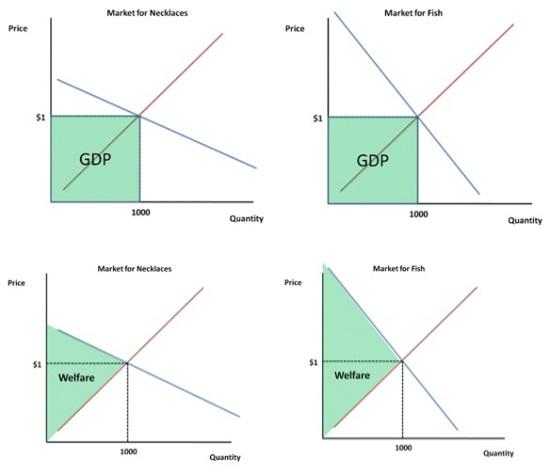

Modeled Behavior illustrates how two goods with the same contribution to GDP as PxQ and the exact same supply curves may yield highly different surpluses depending on the steepness of their demand curves.

Source: Modeled Behavior

Hal Varian writes that economists commonly use two measures to assign monetary value to some good or service: the "compensating variation" and the "equivalent variation". The compensating variation asks how much money we would have to give a person to make up for taking the good away from them while the equivalent variation asks how much money someone would give up to acquire the good in question. The term "consumer surplus" refers to an approximation to these theoretically ideal measures.

Free goods in the information age

If the problem of measuring economic surplus problem of free or cheap goods is as old old as newspapers, libraries, friendship and home production why is the issue coming back with such force with the advent of the information age?

Erik Brynjolfsson and Adam Saunders write that the irony is that we know less about the sources of value in the economy that we did 25 years ago. GDP is a more accurate metric of value in industrial-age industries like steel or automobiles than in information industries.

Tyler Cowen also wondered a couple of years ago if GDP was not going to end up telling us less and less about broader efforts to improve human well-being. Felix Salmon asked this question to Tyler: are you saying that the web has increased the amount of fun that people can have without spending money, or at least has increased the nation’s aggregate fun-to-spending ratio? Are you saying that the correlation between aggregate fun and GDP used to be stronger than it is now, thanks to the advent of the web? Tyler Cowen recently argued that Internet might indeed have higher average consumer surplus. A recent paper by Michael Mandel suggests that it may have been especially true in the recent period with the rise of data-driven economic activities.

Internet consumer surplus: some estimates

The Economist reports the results of a study that asked 3,360 consumers in six countries what they would pay for 16 Internet services that are now largely financed by ads. On average, households would pay €38 ($50) a month each for services they now get free. After subtracting the costs associated with intrusive ads and forgone privacy, McKinsey reckoned free ad-supported Internet services generated €32 billion of consumer surplus in America and €69 billion in Europe.

Hal Varian writes that one way to measure the value of online search would be to measure how much time it saves us compared to methods we used in the bad old days before Google. Based on a random sample of Google queries, researchers found that answering them using the library took about 22 minutes while answering them using Google took 7 minutes. Overall, Google saved 15 minutes of time. (This calculation ignores the cost of actually going to the library, which in some cases was quite substantial. The UM authors also looked at questions posed to reference librarians as well and got a similar estimate of time saved.) In dollar terms, it corresponds to $500 per adult worker per year.

Shane Greenstein of Northwestern University's Kellogg School of Management looked at broadband demand to estimate the consumer surplus from using Internet. Looking at broadband demand, which does have a price, helped capture the demand for all the gains a user would get from using a faster form of Internet access.

The Economist discusses another technique recently employed by Erik Brynjolfsson and Joo Hee Oh. Between 2002 and 2011, the amount of leisure time Americans spent on the Internet rose from 3 to 5.8 hours per week. The authors conclude that in so far as consumers must have valued their time on the internet more than the alternatives, this increase must reflect a growing consumer surplus from the internet, which they value at $564 billion in 2011, or $2,600 per user.