Decoded: BRICS

In the near future, the term ‘BRICS’ may become a synonym for countries whose growth rate returned to normal after achieving rapid growth for a certai

The rapid growth of the BRICS quintet (Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa) was driven by the extraction and export of natural resources and/or the huge input of cheap labour in manufacturing sectors. Having failed to realise an economic structure that ensures sustained and buoyant growth after achieving the status of a high-income country, there is a possibility that these countries may fall into the middle-income trap. Nonetheless, there have been no efforts to avoid this. As a result, in the near future, the term ‘BRICS’ may become a synonym for countries whose growth rate returned to normal after achieving rapid growth for a certain short period of time. This does not mean, however, that the economic attractiveness of the BRICS quintet will disappear soon. Their huge populations coupled with relatively high income levels will continue to attract the attention of the world economy, as they will fuel huge final consumption demand.

The rapid-growth team (India and China) and the normal-growth team (Brazil, Russia, and South Africa)

In 2001, the term ‘BRICS’ was introduced to the world of financial investment. To begin with, the term was merely a coinage using the initial letters of the names of five emerging economies whose markets are home to a certain volume of financial assets and large populations. Therefore, the BRICS initially did not have any mechanism for economic coordination and cooperation with each other. However, as the world focussed its attention on them, the countries conducted an informal summit meeting in 2009. Referred to as the ‘BRICS Summit’, the meeting served to confirm the countries’ mutual cooperation in economic affairs.

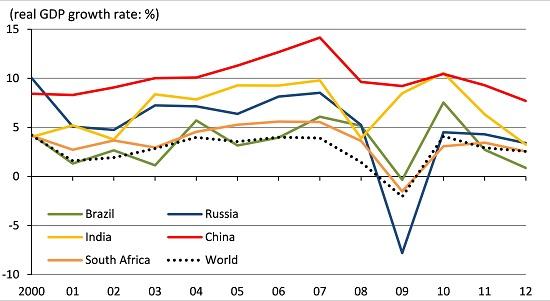

Thus, today, ‘BRICS’ is no longer a mere terminology; rather, it has been transformed into a substantial inter-nation framework that aims to further consolidate the countries’ economic power in the world and strengthen their influence in economic discussions in the international arena. However, Brazil and South Africa have not realised significantly higher growth rate than the world average since the term BRICS came into existence (Figure 1). Traditionally, Russia, India, and China have contributed to the rapid growth in the BRICS framework, but following the Lehman Shock, Russia’s economic growth slowed, as did India’s. The latter’s growth rate decreased to become almost at par with the world average in 2012.

Figure 1: With the exception of China, the real GDP growth rate would be almost the same as the world average

Setback for resource-extracting countries

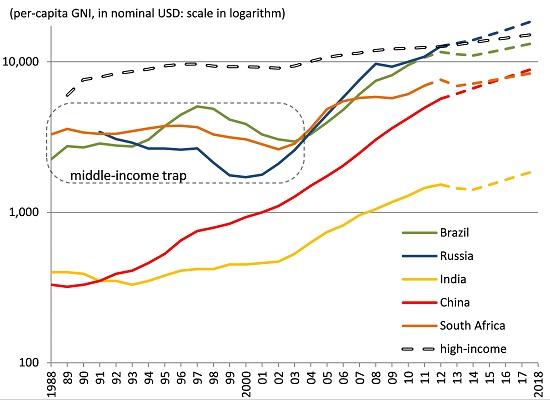

Åslund (2013) expects much lower growth rates in the BRICS than advanced countries over the next decade, and proposes seven reasons limiting BRICS’ rapid growth, including the peak-out of the credit and international commodity booms, moderation in catch-up growth, slowdown in economic reforms, and state and crony capitalism. In its economic outlook published in the autumn of 2013, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) predicted that the growth rates in the gross domestic products (GDPs) for Brazil, Russia, and South Africa would be almost the same as the world average till 2018. Moreover, the IMF forecasts that the per-capita GDP levels for Brazil and South Africa would not approach the lower limit of high-income countries (the dotted black line in Figure 2).[1]

In other words, it is possible that Brazil and South Africa may fall into the ‘middle-income trap’. This term refers to a situation where in a country that has achieved the status of a middle-income country merely by extracting its natural resources for export, or by using its abundant and cheap labour force in export manufacturing, finds it difficult to develop further and achieve the status of a high-income country. This is because the country is ‘unable to compete with low income, low wage economies in manufacturing exports and unable to compete with advanced economies in high skill innovations’ (ADB, 2011: 9). In fact, Brazil, South Africa, and Russia had fallen into such a trap between the late 1990s and early 2000s (Figure 2). Although they seem to have succeeded in extricating themselves from the trap in 2004, this was only possible due to the sharp rise in the prices of international commodities they exported.

Figure 2: Setback in the growth rates of the BRICS countries

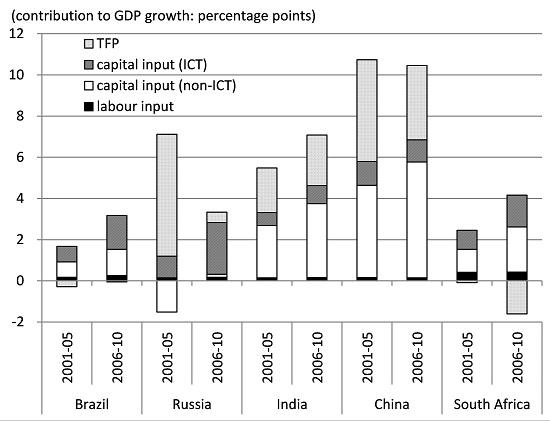

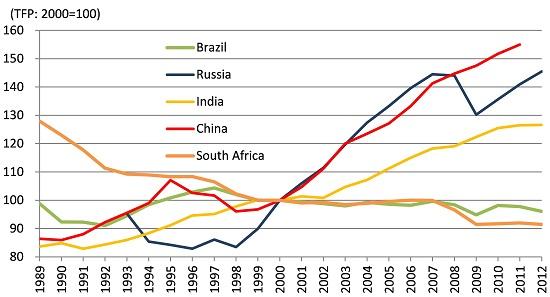

This ‘luck’ made them hesitant to change their economic structures, even though they had experienced the middle-income trap. This discussion on the middle-income trap teaches us that in order to realise the sustained and buoyant growth that goes into making a high-income country, the concerned country should have a productivity-driven economic structure. However, Figure 3(a) shows that the change in total factor productivity (TFP) does not contribute to economic growth in Brazil, Russia, and South Africa. Moreover, historically, the TFP of Brazil and South Africa has declined (Figure 3(b)).

Figure 3: Low TFP growth in Brazil, Russia, and South Africa

(a) Contributions

(b) Time series

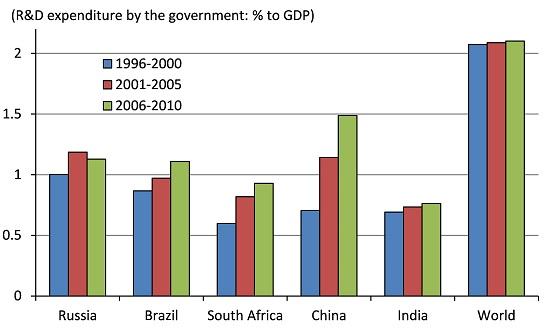

This slow increase in their productivity may stem from the weak efforts of their governments toward promoting innovation and research and development (R&D), which are crucial for productivity growth. Figure 4 shows the countries in order of decreasing income levels. In general, the ratio of the governments’ budget expenditures on R&D to GDP is higher in the countries with higher income levels. Accordingly, of the five countries, China can be assessed as being the most aggressive in establishing a base for productivity growth. However, the amount of spending for R&D is below the world average for all the BRICS countries. As R&D investments typically bear fruit several years later, the lack of efforts to establish a base for productivity growth in Brazil and South Africa might deter them from achieving the high-income country status in the near future.

Figure 4: The extent of the government’s efforts toward encouraging R&D

Can China and India sustain their rapid growth in the near future?

China and India do not differ much from the remaining three BRICS countries. Figure 3(a) shows that non-ICT capital input has been the main driving force of these countries’ economic growth in the 2000s, i.e., their growth has been resource-oriented. Their high TFP growth rates may be attributed to a side-effect of labour migration. In general, rapid industrialisation in urban areas motivates the surplus labour force (with zero or negligible productivity) in rural agricultural sectors to migrate to urban manufacturing sectors which realise higher productivity. Therefore, migration itself would increase the TFP growth rate without increasing wages, as long as an abundant surplus labour force exists in rural areas. Once the surplus labour force becomes scarce, an input-driven growth model would no longer be applicable, because the country concerned will have its competitiveness diminished due to the wage increase.

Given this, are China and India unable to eventually become high-income countries? Åslund (2013) sees that the growth rate of these two countries peaked out in 2010, and expects lower growth rates in the near future. According to the IMF’s latest Economic Outlook in October 2013, however, China will maintain a higher growth than the world average (though its growth rate is expected to decrease gradually), and India’s growth rate will gradually recover and approach that of China (slightly below 7% in 2018). China has limited time to change its growth model from an input-driven one to a productivity-driven one, but, as seen from Figure 4, the government is making efforts to do so. India, on the other hand, still has longer time, as seen from its current income level. Thus, India should (and can) deliberately consider its long-term strategy for economic development in order to avoid the middle-income trap and achieve the high-income status.[2]

The attractiveness of the BRICS quintet has not diminished

Åslund (2013) sees that high growth rates in the BRICS quintet are over, due in part to poor governance, reluctance to economic reform and spread of state and crony capitalism in them. This may be true, but the role of the BRICS quintet in the world economy itself will not be over even though their economic growth rates decline.

There are two reasons to think so. One is that, after having made their debut on the stage of economic diplomacy, the BRICS countries cannot merely be destinations for financial investment. This, at the same time, imposed the BRICS quintet to fulfil their responsibility to the world by realising resilient and transparent markets, so that the world economy need not bear any economic risks stemming from the huge financial flows through their markets. Besides, it may be difficult for the BRICS quintet to have the economic influence in the world with normal economic growth rate alone. Therefore, if the BRICS countries are to maintain their economic influence in the world, they should make timely changes to their economic structures in order to realise sustained and buoyant economic growth.

The other is that they currently offer, and will continue to offer in the near future, the ‘new’ attractiveness as final destinations of a huge amount of consumption. Crucially, the BRICS countries share another vital characteristic beyond their past rapid economic growth which has always attracted the attention of the world economy. They have a huge combined population (42.8% of the world total), and their economic development almost approaches that of the high-income countries (though India will take some more time to reach this level). These two conditions generate a considerable ‘middle-income stratum’. The people in this stratum which has as large as 1.64 billion population as of 2011 and is still expanding, will increase their consumption in the near future.[3]

In short, the BRICS may finish their ‘old’ role as the emerging market but will have a ‘new’ role for the world economy as the centre of consumption power. Now is time to shift our focus from the enthusiastic boom in the BRICS countries’ financial markets to the new attractiveness inherent in their real economies. Speeding up regulatory reforms (such as easing foreign business regulations) and efforts to develop a highly productive economy are the need of the hour so that these countries may capitalise on this attractiveness and continue expanding their middle-income strata.

The original version was released in Japanese by National Institute for Research Advancement on 26 December, 2013.

Akio Egawa is senior researcher at NIRA, Japan / former visiting fellow at Bruegel.

References

Asian Development Bank, 2011 “Asia 2050: Realizing the Asian Century” Manila.

Åslund, Anders, 2013 “Why Growth in Emerging Economies Is Likely to Fall” Peterson Institute for International Economics Working Paper Series WP13-10, November 2013.

Rodrik, Dani, 2013 "The Perils of Premature Deindustrialization” Project Syndicate Website.

Notes

[1] Figure 2 shows that Russia’s per-capita GDP would exceed the lower limit of the high-income countries in 2012 and then grow to exceed this limit in nominal dollar terms, whereas its real GDP growth rate would be almost the same as the world average. Taking other conditions into account, the development of prices in the future may affect Russia’s faster per-capita GDP growth in nominal dollar terms.

[2] Rodrik (2013) states that even though the consequences have yet to be analysed in full, deindustrialisation at substantially low income levels would impede growth and delay convergence with the advanced economies. One reason is that as labour productivity in manufacturing industries tends to converge with the advanced economy more rapidly, deindustrialisation would hamper this effect.

[3] Based on data from the Euromonitor International Inc. (which is often used in other studies in the field), a person in the middle-income stratum is defined as a member of a household with an annual disposable income of 5,000 to 35,000 US dollars in nominal terms.