Will voters turn out in the 2014 European parliamentary elections?

The extent of voter turnout in the 2014 European Parliamentary (EP) election is widely viewed as a critical test for European democracy. This may well

The extent of voter turnout in the 2014 European Parliamentary (EP) election is widely viewed as a critical test for European democracy. Turnout in the EP elections has steadily declined over three decades from 62 percent in the first election in 1979 to 43 percent in the 2009 election. There is great concern that the legitimacy of the European Union is at stake should there be a further slide in voter turnout. Such legitimacy is of particular concern since the crisis has been accompanied by a growing European divide—between the “north” and the “south,” between the “core” and the “periphery.” Greater voter turnout will affirm a willingness to bridge the divide, to share the hardships, and forge ahead. This may well be the most important EP election ever, and the European Commission has set an ambitious goal of increasing voter participation.

Eurobarometer surveys report a sharp increase in mistrust of European institutions since the start of the crisis, which bodes ill for voter turnout. Some, however, take the view that the increased authority of the European Parliament under the 2009 Lisbon Treaty could galvanize voters to leverage that authority into a renewed effort for greater European solidarity and prosperity.

Our analysis suggests that the lack of trust, especially in the ability of European institutions to provide financial stability and safety nets, will dominate the voting decision, leading to a further fall in turnout to 40 percent or even lower.

Debating causes of low turnout

The dominant explanation for low voter turnout in EP elections has been that voters deem the European parliament to be of minor importance to their lives. EP elections are “second-order national elections” because voters do not view their direct interests to be at stake. As such, Sara Hobolt and Jill Wittrock (2011) note, voter turnout is lower and representation of smaller parties is higher in EP elections than in national elections. Simon Hix and Michael Marsh (2007) also emphasize that voting for the EU parliament often reflects an urge to send a signal of disapproval to the national government, rather than being an anti-EU protest vote.

However, Hix has recently argued that the 2014 EP election could be different and offers a real opportunity to shape European politics. In particular, the call for political parties to announce their preference for a Commission President before the elections - and the presumption that the European Council will defer to this choice - could induce a higher turnout.

A second, more structural explanation for continued decline in voter turnout is changing demographics. Higher voter turnout in earlier EP elections reflected the commitment of the baby-boomer generation to Europe and, hence, to the EU parliament. As the baby-boomers age, the trend in lower voter turnout is likely to persist.

Trust in the ECB

Perhaps both of these two factors will remain at play in the forthcoming election. Yet we argue for a closer examination of how economic incentives impact turnout in EP elections. Kimmo Grönlund and Maija Setälä (2007) find that trust in political institutions helps boost turnout. In the current European context, rather than a general sense of trust, a more specific consideration could be at play. We examine the proposition that the ability to provide meaningful financial stability and relief is the salient dimension of how voters assess institutions. We find that trust in the European Central Bank (ECB), as the key player determining monetary and financial policy, appears a critical factor in explaining changes in voter turnout.

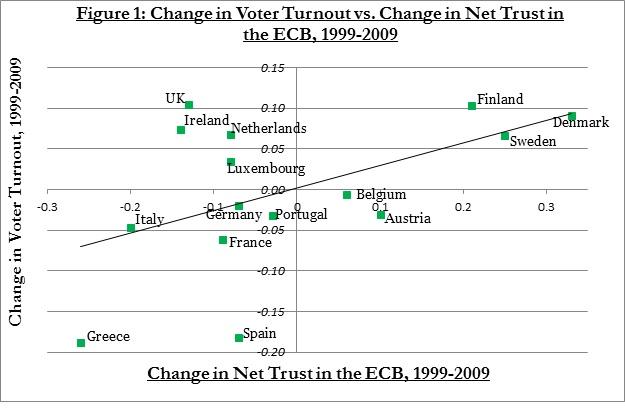

Figure 1 shows changes in voter turnout between 1999 and 2009 against changes in net trust (those reporting trust minus those reporting mistrust) in the ECB over the same period. The data for both voter turnout and net trust in the ECB is plotted for the 15 EU member states that participated in the EP elections in 1999, 2004, and 2009. There seems to be a prima facie relationship between voter turnout and trust in the ECB. Notice, in this graph and in the regressions below, European countries outside of the euro area are also included: these countries also report perceptions of trust in the ECB. This measure, therefore, reflects not just what the ECB does directly for the euro area countries but also a broader notion of financial stability in Europe.

Sources: European Commission, Eurobarometer Surveys, “Trust in Institutions – The European Central Bank.” International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance (IDEA), “Voter Turnout Database, Europe, EU Parliament.”

Notes:

- Data on trust in the ECB is taken from the bi-annual Eurobarometer public opinion surveys for the period from1999-2009, which draw from a random selection of respondents aged 15 and over from the population in each EU member state.

- Net trust in the ECB = Trust in the ECB – Mistrust in the ECB. This metric was introduced by M. Gärtner in 1997 and used recently by Felix Roth, Felicitas Nowak-Lehmann, and Thomas Otter in 2013,

- Building from the basic relationship charted above, we estimated multivariate regressions to determine how voter turnout is influenced by several covariates of interest, using both fixed effects and random effects panel models. We use the results from the random effects model presented below for our predictions of voter turnout. Net trust in the ECB remains significant in the same specifications run in a fixed effects model. Bottom line: reduced trust in the ECB has been associated with reduced turnout.

Sources: International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance (IDEA), “Voter Turnout Database, Europe, EU Parliament.” Eurostat, Government Finance Statistics, “Government deficit and debt.” European Commission, Eurobarometer Surveys, “Trust in Institutions – The European Central Bank.”

Notes:

- Net trust in the European Parliament is calculated identically to net trust in the ECB, i.e. Net Trust = Trust – Mistrust.

- We note the concern that random effects models assume that the predictor covariates included capture all relevant between-country variance, or else it is vulnerable to omitted variable bias. A random effects model is used here in order to obtain more accurate predictions by country - unlike in a fixed effects model, we can include important covariates, such as compulsory voting, that do not change in a given country over time.

- We assume, as reported inliterature on compulsory voting in Europe, that the compulsory voting laws in Greece and Cyprus are weakly enforced (if at all), and thus these countries are coded as non-compulsory voting in the data-set.

Interpretation

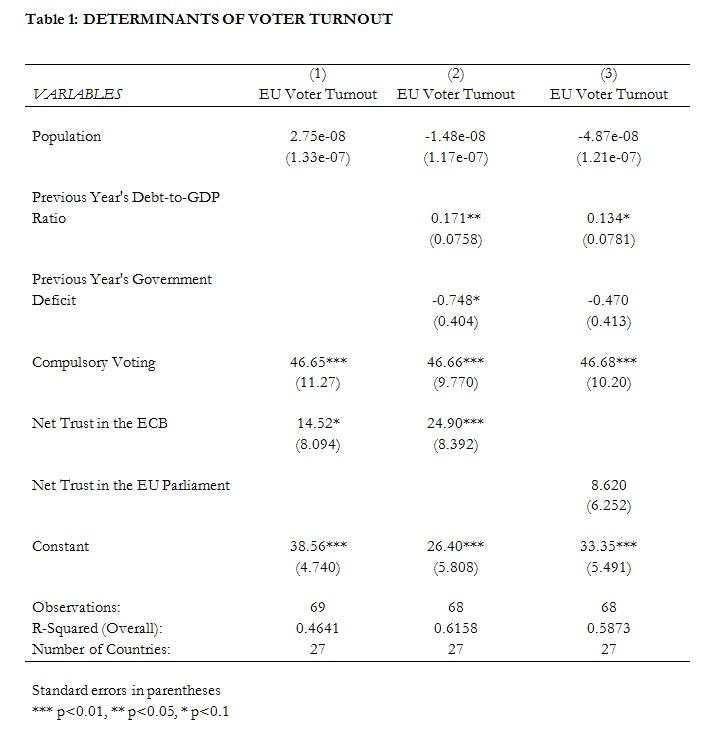

In Table 1, the population variable controls for country size: in general, smaller countries tend to have higher voter turnouts. We explored a number of economic variables as possible correlates of voter turnout; these included the previous year’s GDP growth, unemployment rate, and inflation rate. However, the two economic variables that are statistically salient are the ones that represent fiscal stress: the previous year’s debt-to-GDP ratio and previous year’s government deficit. The coefficients on both variables enter with a negative sign, implying that greater fiscal distress is associated with a higher voter turnout. In other words, where a country’s fiscal problems are greater, voters are more inclined to vote. This could reflect the hope that a stronger Europe will provide fiscal relief.

Notice, also that trust in the European Parliament itself is not correlated with voter turnout. In other words, trust in the European Parliament does not draw voters, an observation that questions the likelihood that procedural changes in this election will have a material influence on voter turnout. Instead, the ability to deliver financial relief through the ECB or alleviate national fiscal distress helps create a more benign attitude to Europe, leading to higher voter turnout.

Predictions

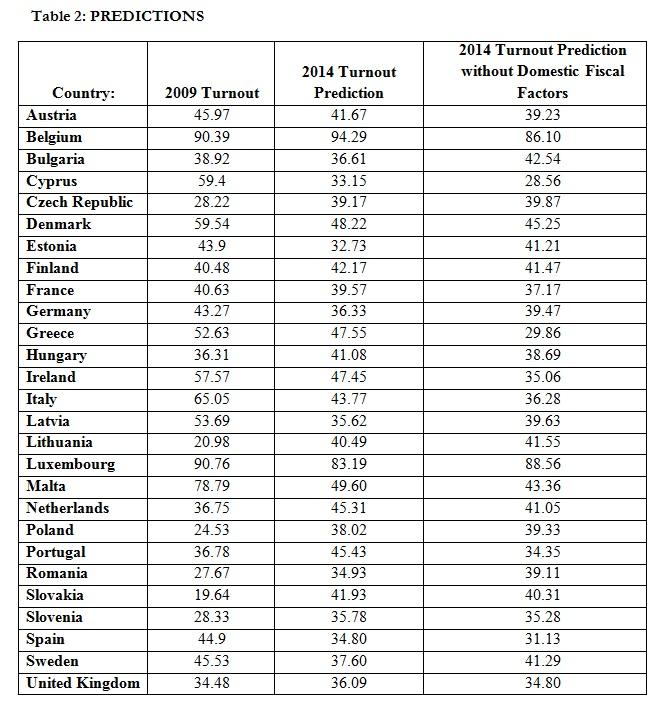

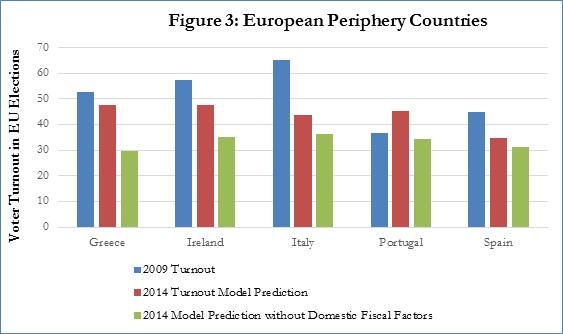

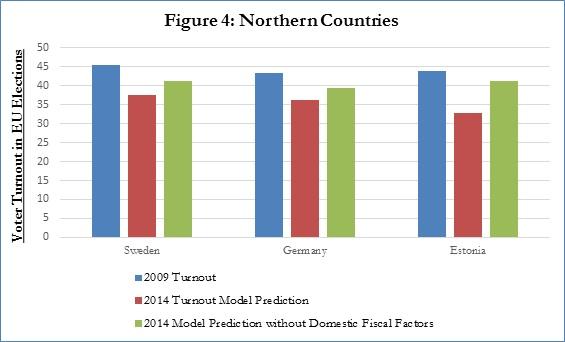

Building on these regression findings, we predict expected 2014 voter turnout in EU member states based on the latest data on fiscal variables of debt-to-GDP ratio, government deficit, and the net trust in the ECB (Table 2). The projection labelled “2014 Turnout Model Prediction” utilizes the full model, Model 2 in the regression specification, whereas the projection labelled “2014 Model Prediction without Domestic Fiscal Factors,” uses Model 1 in the regression table above. Thus we provide two predictions for each EU member state. The predictions from the full model include the mediating effects of fiscal covariates. The other model discounts the possibility that greater domestic fiscal stress will cause people to look to Europe and places the spotlight on trust in the ECB.

Notes:

- A 2014 projection for population of each EU member state is drawn from the IMF World Economic Outlook database in order to use an up-to-date figure for turnout predictions.

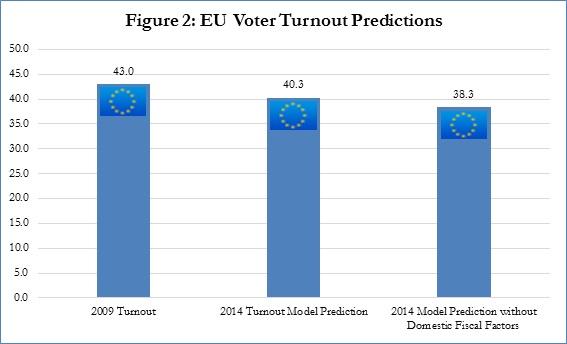

Figure 2, which summarizes the results, says that voter turnout will likely fall from 43 percent in 2009 to between 38 and 40 percent. The higher turnout of 40 percent would reflect some expectation of relief of national fiscal distress from Europe. Even so, it would not be enough to offset the precipitous decline in trust in the ECB. We are inclined to favor the lower end of our predictions. In the past, as Karl C. Kaltenthaler and Christopher J. Anderson (2001) also found, nationals of an EU member state were more likely to turn to Europe when their national authorities did not deliver. However, those past expectations have been belied during the recent crisis when that help from Europe was limited, and grudging.

Focusing on specific countries, a higher voter turnout in the expectation of greater fiscal support from Europe would most likely occur, not surprisingly, in the European periphery countries, where fiscal conditions have deteriorated the most and the need for relief is the greatest (Figure 3). In Portugal, this possibility may even raise the voter participation from the previous election. Elsewhere in the periphery, however, with or without such expectation, voter turnout will likely fall, possibly quite steeply, as in Italy.

In contrast, in the “north,” voter turnout is expected to be low not only because of reduced trust in the ECB but, possibly, in addition because their fiscal situation does not require support from Europe (Figure 4).

A Guide to Interpreting the Turnout

The EP elections should give us some insight on whether the strengthening of the European Parliament is sufficient to foster a reaffirmation of a European vision, or whether more tangible economic benefits are needed for that confidence to emerge. To be clear, these are merely rough predictions – predicting an exact voter turnout is notoriously difficult and can be contingent on factors that vary by the day, such as weather. Nevertheless, the results should help us evaluate the turnout that does transpire. If it is in the range we predict, it will be consistent with past patterns and the fall will mainly reflect the already visible loss in faith in Europe’s financial capacity and sense of solidarity. If, moreover, the fall in voter participation is greater in the periphery, it will confirm a growing European divide between debtors and creditors. If overall voter turnout is lower than 38 percent, that would imply greater doubts about European democracy than past patterns suggest, and possibly an indictment of the European Parliament. In contrast, a voter turnout in the 40-43 percent range—and even more so a turnout above the 2009 turnout of 43 percent—would normally signal hope that solidarity can yet be achieved. The risk, of course, is that the higher turnout is driven by a strong anti-European sentiment.

References

Banner, Helene, and Maria Zandt, 2009, “How the Turnout at European Elections Could be Much Higher…in 2014," Interview with Simon Hix, from the Euros blog, accessed at: www.theeuros.eu/How-the-turnout-at-European,2844.html?lang=fr

Bhatti, Yosef and Kasper Møller Hansen, 2013, "Turnout at European Parliament Elections is Likely to Continue to Decline in the Coming Decades," LSE, European Politics and Policy Blog.

European Commission, “European Parliament Elections – Getting Out The Vote,” March 13, 2013, accessed at: http://ec.europa.eu/news/eu_explained/130313_en.htm

European Parliament/Liaison Office with U.S. Congress, "European Elections 2014," accessed at: www.europarl.europa.eu/us/en/elections_2014.html

European Parliament, “Turnout at the European Elections (1979-2009),” accessed at: http://www.europarl.europa.eu/aboutparliament/en/000cdcd9d4/Turnout-(1979-2009).html

Gratschew, Maria, 2004, "Compulsory Voting in Western Europe," Voter Turnout in Western Europe, International IDEA publication, accessed at: http://www.idea.int/publications/voter_turnout_weurope/upload/chapter%203.pdf

Grönlund, Kimmo and Maija Setälä, 2007, "Political Trust, Satisfaction and Voter Turnout," Comparative European Politics, 5, (400–422).

Hix, Simon and Michael Marsh, 2007, “Punishment or Protest? Understanding European Parliament Elections,” Journal of Politics, Vol. 69, No. 2, pp. 506-507.

Hobolt, Sara Binzer and Jill Wittrock, 2011, "The Second-Order Election Model Revisited: An Experimental Test of Vote Choices in European Parliament Elections," Electoral Studies 30.

Gärtner, M, 1997, “Who Wants the Euro - and Why? Economic Explanations of Public Attitudes Towards a Single European Currency,” Public Choice 93: 487-510.

Kaltenthaler, Karl C. and Christopher J. Anderson, 2001, "Europeans and Their Money: Explaining Public Support for the Common Currency," European Journal of Political Research, 40: 139-170.

Roth, Felix, Felicitas Nowak-Lehmann, and Thomas Otter, 2013, “Crisis and Trust in National and European Union Institutions - Panel Evidence for the EU, 1999-2012,” European University

Institute Working Papers, RSCAS 2013/31.