Blogs review: The economics of Scottish independence

What’s at stake: With the referendum on Scottish independence scheduled for September 2014 coming closer, the debate about the economics of Scott

What’s at stake: With the referendum on Scottish independence scheduled for September 2014 coming closer, the debate about the economics of Scottish independence is intensifying. Last week, the UK and Scottish governments both published papers on the effects of Scottish independence on public finances. While Danny Alexander, Chief Secretary of the UK Treasury argued that there is a “UK Dividend” worth around £1400 per capita per annum, the Scottish First Minister Alex Salmond claims, based on the Scottish government’s calculations, that an “independence bonus” would be worth £2000 per person and year.

On fiscal dividends of union or independence

David Eiser digs out the different underlying assumptions driving the results of the UK and Scottish government papers. The Scottish government assumes higher oil revenues for Scotland and a more favourable settlement with the UK on the partitioning of national debt. Post 2016, the UK report accounts for a higher premium on debt repayments, a (controversial) measure of the set-up costs of new government institutions (see below) as well as costs and benefits of three major policy proposals by the Scottish government. The Scottish report, on the other hand, factors in three positive economic developments – higher productivity growth, employment rates and immigration – which look credible in scale, but are not deduced from concrete policy proposals.

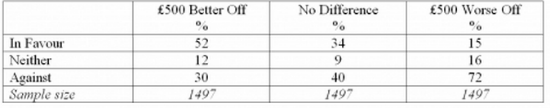

Charlie Jeffery emphasizes the importance of such estimates for the referendum’s outcome: The best predictor of an individual’s vote is his or her assessment of the effects on her or his personal economic fortunes. Confronted with the ‘£500 question’, being either £500 better off if Scotland were independent, or £500 worse off, a majority of survey respondents were in favour of independence if they were better off and against, if they were worse off.

Fig.1: Attitudes to the “£500 Question”, 2013

Source: Scottish Social Attitudes 2013 in John Curtice, The Score at Half Time: Trends in Support for Independence via Charlie Jeffery

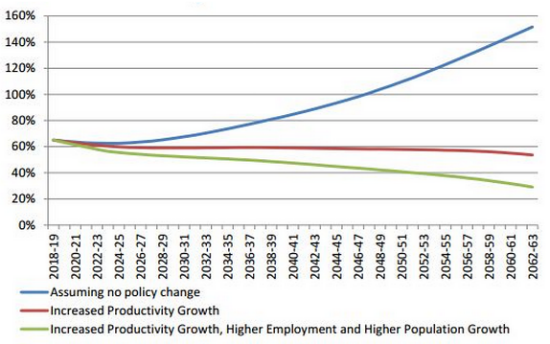

John McDermott argues that the £2000 “independence bonus” is not based on an assessment of policies proposed by the Scottish National Party (SNP), but simply on the assumption that three good things will happen: A productivity growth increase by 0.3 percentage points, an increase in the employment rate by 3.3 percentage points and an increase in Scotland’s working age population. Without these positive developments, Scotlands fiscal future looks less rosy. And as the “additional boost” to tax revenues is compared to a different scenario for a hypothetical independent Scotland, rather than to Scotland as part of the UK, the bonus is not an independence bonus at all.

Fig. 2 Debt Projections for Scotland under 3 scenarios

Source: The Scottish Government

Martin Wolf regrets that the debate on such an important topic is too focused on relatively short-term economic effects. On the economic prospects, however, the UK government seems to be right and in agreement with research by independent bodies such as the Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS) (which is quite optimistic on the current debt trajectory for the UK, but finds that the public debt of an independent Scotland would increase every year as a share of national income and exceed 100% of national income by 2033–34 unless harsh policy action is taken): The Scottish fiscal position is now already slightly worse than that of the UK as a whole and receipts from North Sea oil are likely to fall. And the Scottish government’s plans for the economy – increasing productivity growth, labour force participation and immigration – are not guaranteed to work.

Brian Ashcroft attempts to elucidate whether a “UK dividend” exists outside of hypothetical scenarios by comparing total managed expenditures (TME) in Scotland with tax revenues under independence (including a share of oil revenues), without taking into account hypothetical future changes in policy or transition costs. In this thought experiment, Scotland would have indeed been marginally better off under independence in the last 5 years – but just by £193 million of £8 per person per year and with a negative outlook for the future.

Set-up costs for a new state

The UK government directly challenged the Scottish government to provide estimates of the costs of setting up an independent Scotland, arguing – based on research on Quebec – that costs could reach up to 1% of GDP, equivalent to £600 per household and £1.5 billion in total. Using estimates by the Institute for Government at the LSE, the costs of setting up a new department are at around £15 million, which would add up to a total cost of £2.7 billion to Scottish taxpayers.

Patrick Dunleavy, on whose research the £15 million per department figure is based, finds his research woefully misapplied: The £15 million referred to setting up Whitehall-scale departments, the “Rolls Royce of administrative machines”, whilst smaller solutions are feasible for Scotland. Accounting for the enlargement of current Scottish Executive directorates, with common HR and IT systems, and the creation of four additional ministries (defence, foreign affairs, finance and welfare), Dunleavy guesstimates that set-up costs of an independent Scotland may amount to £150-200 million. Disentangling antiquated tax and welfare IT systems may be more costly, but the creation of new systems might also lead to efficiency gains.

Robert Young argues that in implementing a possible independence of Scotland from the UK, some issues such as the nuclear deterrent and the currency would involve hard negotiations, whereas the disentangling of administrations would be costly due to the need for attention to details. Significant transaction costs should be expected - Dunleavy’s argument that basically just 4 ministries are required neglects that many specialized agencies would be required – however, through cooperation with the UK (such as a joint vehicle licensing agency), these costs can be managed.

Oil revenues as a major determinant of Scottish public finances

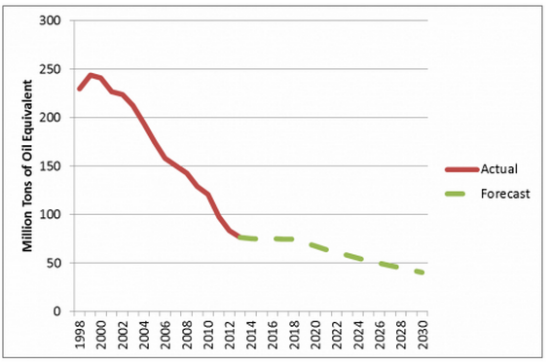

Gemma Tetlow focuses on the forecasts for North Sea oil revenues in the two papers. Depending on whether revenues forecasts by the Office for Budget Responsibility (used by the UK government) or the Scottish governments own, more optimistic, forecasts are used, North Sea oil revenues amount to 1.7% (OBR) or 4.1% (Scottish government) of Scottish GDP. As forecasts and outturns of oil extraction have diverged in the recent past, it is difficult to say, which figures are correct. Yet, the public finances of a Scottish state would certainly be highly sensitive to oil revenues.

Fig. 3 Actual and Forecast Oil Production

Source: DECC/David Bell

David Bell notes that the volume of oil and gas production in the North Sea has been falling sharply in the past, with a more gradual decline expected for the future. At the same time, oil prices have risen in the past, but have stabilized since 2011. However, assumptions made on production volume and oil prices do not fully account for the sharp differences between the OBR and Scottish figures for oil revenues. The Scottish government may have made somewhat more optimistic assumptions on cost developments, but in the past, cost inflation has been a particular problem for operators – which is bad news for tax revenues, as taxes are levied only after costs have been covered. Finally, the (lower) OBR forecasts for oil revenues themselves have been optimistic compared to turnouts in the past.

Currency questions

Simon Wren-Lewis explores the consequences of the SNP’s favoured strategy of remaining in a Sterling currency union. While the Bank of England (BoE) could continue to set interests rates according to an inflation target for the whole currency union, keeping the costs of the currency union for Scotland quite low, it is far less likely that the BoE would be acting as a lender of last resort for Scottish government debt. This could result in the Scottish government finding itself in a bad equilibrium with high interest premiums on its debt, similar to the Eurozone periphery in recent years. Getting the UK to allow the BoE to act as lender of last resort for Scotland may, in case of crisis, be coupled to highly restrictive and economically harmful fiscal policies that the UK, similar to Germany, believes in. So rather than accept damaging fiscal restrictions, the new Scottish government may end up with its own currency after all.

Angus Armstrong and Monique Ebell make a similar point. They estimate that, in a currency union, Scotland would face an interest rate spread of .72% to 1.65% above the UK borrowing costs for 10 year debt, implying that the government would have to run a tighter fiscal policy: Scotland would need to run a 3.1% primary surplus to achieve the Maastricht 60% debt to GDP criterion within 10 years of independence, representing a 5.4% fiscal tightening. The more debt Scotland would inherit, the stronger would be the case for having its own currency.