Easier monetary policy should be no worry to Germany

As the ECB this week meets for a governing council meeting, markets have priced in a next easing of monetary policy.

See also policy contribution 'Addressing weak inflation: The European Central Bank's shopping list', interactive map 'Debt & inflation' and comment 'Negative ECB deposit rate: But what next?'.

As the ECB meets this week for a governing council meeting, markets have priced in a next easing of monetary policy. I spent some time last week at the first Sintra conference of the ECB, a conference that aims to become the European "Jackson Hole" for central bankers. Besides the beautiful setting, I took away that the ECB is quite aware of the problem of low inflation and the need to do further monetary stimulus. Most likely, we will see a cut in the rate combined with an LTRO-type funding for lending scheme. There may also be a more explicit announcement of an asset backed securities (ABS) purchase programme, not least in order to let the private sector make the necessary preparatory steps to increase the market from its current size of around €330bn of ABS that can be used in collateral at the ECB . To my mind, the ECB should move ahead as quickly as possible in order to minimize the substantial risks coming from low inflation rates.

Some commentators fear, however, that further monetary policy action could lead to dangerous developments in Germany. I would argue to the contrary: an increase in inflation rates in Germany should be welcomed. German year-on-year annual inflation rate was 1.1% in April and the flash estimate for May is a y-o-y inflation of only 0.6%. The rate is hence well below the 2% target while in fact it should stand well above that level in order to allow for a relative price adjustment in the monetary union around 2%. Such an increase in inflation would not lower purchasing power of German households as it would be driven by higher wage developments and would actually increase German purchasing power throughout the Euro area.

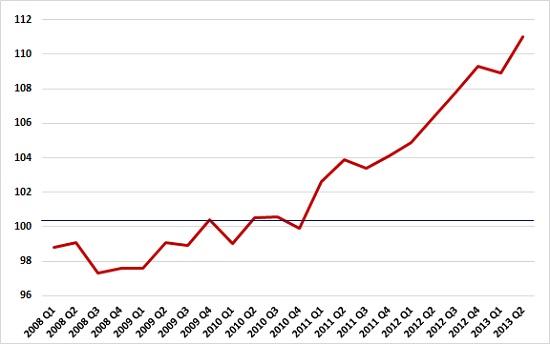

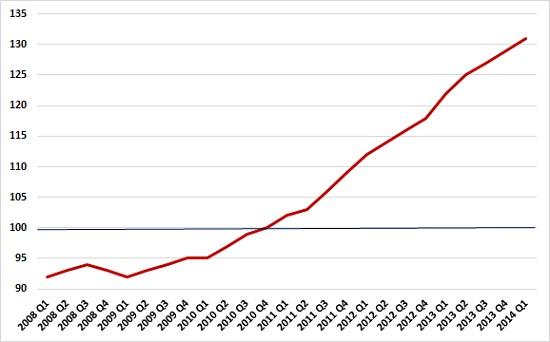

A more serious concern raised by some is that Germany developed a housing bubble that may undermine financial stability in Germany. In fact, house prices have risen quite substantially in Germany in the last couple of years. Overall, house prices increased by 11% since 2010. It is worth noting, however, that the price development in Germany is mostly driven by regional dynamics. While prices increased rather moderately in rural areas, prices for apartments in the 7 biggest cities went up by around 30% as shown in the graphs below.

But is this a risk to financial stability? Should the ECB accompany its monetary policy activism with macro prudential policies to slow down the German housing market? This is far from clear. In fact, financial stability would only be an issue if there is a risk that the housing market may turn substantially and as a consequence non-performing loans would increase significantly.

Figure 1: House price index, 2010 = 100

Source: Bundesbank, quarterly data

Figure 2: Price index for apartments in 7 major cities, 2010 Q4 = 100

Note: Berlin, Hamburg, Munich, Cologne, Frankfurt am Main, Stuttgart and Düsseldorf, source: Bundesbank

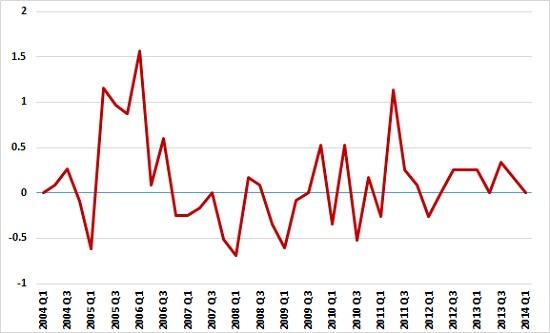

The graph below shows, however, that the housing boom is not driven by an increase in credit and mortgages. Indeed, credits volumes are still very subdued and mortgage growth is sluggish. Leverage in the corporate and in the household sector is also very weak. The consumer credit annual growth rate stood at 1.3 percent at the end of April 2014 as can be seen in figure 4 and the corporate sector as a whole is still a net lender. So overall, there is no reason to worry that monetary policy would be too expansionary for Germany. On the contrary, there is rather the question whether monetary policy will be enough to accelerate German demand sufficiently. It is hard to argue based on these numbers that the German economy is overheating. I would argue that in addition, Germany should increase its public investment and lead a European investment programme to further strengthen demand.

Figure 3: Mortgage growth to domestic corporations and private persons, in %, quarterly data

Source: Bundesbank

Figure 4: Annual household credit growth

Source: ECB

Excellent research assistance by Olga Tschekassin is gratefully acknowledged.