Blogs review: The secular stagnation hypothesis

What’s at stake: On November 16, the Harvard economist and former Treasury Secretary Lawrence Summers gave a provocative talk at an International

The return of an old hypothesis

John Taylor summarizes Larry Summers’ argument (full transcript available here) that a decade long secular decline in the equilibrium real interest rate explains both the lack of demand pressures before the crisis and the slow growth since the crisis:

- In the years before the crisis and recession, easy money and related regulatory policies should have shown up in demand pressures, rising inflation, and boom-like conditions. But the economy failed to overheat and there was significant slack.

- In the years since the crisis and recession, the recovery should have been quite strong, once the panic was halted. But the recovery has been very weak. Employment as percentage of the working age population has not increased and the gap between real GDP and potential GDP has not closed.

- A long secular decline in the equilibrium real interest rate offset any positive demand effects of the low interest rate policy before the crisis. And, with the zero interest rate bound, the low equilibrium interest rate leaves the economy weak even with the current monetary policy.

Bruce Barlett writes that the specific term “secular stagnation” is one familiar to an earlier generation of economists. Many believed that the Great Depression had permanently changed the long-term trend rate of economic growth that was possible given the rate of growth of the population, technological progress and the decline of investment opportunities, among other things. The principal spokesman for this view was the Harvard economist Alvin Hansen.

Savings glut, investment dearth and the role of negative interest rates

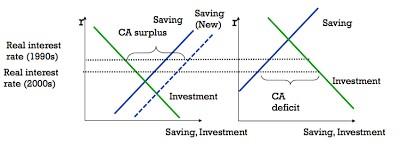

Arnold Kling writes that Summers’ story is one of a permanent shortfall of aggregate demand, due to an excess of desired saving over desired investment, which can only be eliminated at a negative real interest rate.

Antonio Fatas writes that what was interesting about the saving glut hypothesis is that it not only explained the decrease in interest rates but it was also able to account for the growth in global imbalances. But in this story there were some predictions that were never tested. In particular, as interest rates fell, investment should have increased globally. If you look at the saving and investment curves, investment should have increased both in countries where the supply of saving was shifting as well as in the other countries. Did we see that? No. In fact in advanced economies we have seen the opposite. The aggregate investment rate (as % of GDP) fro OECD countries went from 25% in the 1980s to 19% today.

The only way to make this last chart compatible with the saving glut story is to argue that at the same time that the saving curve was shifting to the right in some countries, the investment curve was also shifting (this time inwards) in other countries.

Kevin Drum writes that there simply aren't enough promising real-world investments available, at current interest rates. It doesn't matter that real interest rates are already negative. Reduce them even further, and more investments will look like winners.

Miles Kimball writes that people are shocked by negative interest rates. It basically means you're paying a storage company — the bank — to store your money, and there are circumstances where that's the way the economy should work. Many times, the economy desperately wants people saving, and interest rates will be positive and strong, but you get other periods of time when people are actually reluctant to borrow, because companies are scared of whether they can make a good profit by investing and buying new equipment or building a factory, and people are scared to buy automobiles or build a home. Like any change in prices, it helps some people and hurts others, but in a broader sense by getting employment back in gear, it helps everyone.

Moore’s law of cheaper capital goods, risk premiums and demographic factors

Larry Summers says (see 1:17:17 in this video) that we need a different investment savings balance now that the capital goods are substantially cheaper. The relative price of information technology is going down 20% per year, so the same amount of savings is producing vastly more capital every year. Arnold Kling notes that the “savings glut” did not just come from foreign sources but from the fact that the cost of obtaining capital in the form of computing equipment kept falling, making investment demand too low to absorb savings and creating a state of chronic excess supply in capital markets. Martin Wolf notes that the share of real investment actually remained stable. It is the nominal investment share that shrank.

Tyler Cowen writes that we’ve had negative real rates on government securities, but positive rates on many other investments in the U.S. The difference reflects a very high real risk premium, which of course we would like to lower, and the differences also reflect some degree of investment segmentation.

Paul Krugman writes that back in the day Hansen stressed demographic factors: he thought slowing population growth would mean low investment demand. Then came the baby boom. But this time around the slowdown is here, and looks real. Think of it this way: during the period 1960-85, when the U.S. economy seemed able to achieve full employment without bubbles, our labor force grew an average 2.1 percent annually. In part this reflected the maturing of the baby boomers, in part the move of women into the labor force. This growth made sustaining investment fairly easy: the business of providing Americans with new houses, new offices, and so on easily absorbed a fairly high fraction of GDP. Now look forward. The Census projects that the population aged 18 to 64 will grow at an annual rate of only 0.2 percent between 2015 and 2025.

Problems with Summers’ hypothesis

Arnold Kling writes that Summers offers an answer that is vague but sounds clever. He then leaves it to other people to come up with a precise version. Unfortunately, the precise versions are problematic, meaning that they are either unsound in terms of theory, inconsistent with evidence, unable to support the explanation and policy implications of the vague version, or all three.

Stephen Williamson writes that Summers wants to somehow connect secular stagnation to the zero lower bound. This is puzzling, as it runs into the same problem as in the standard Keynesian narrative. In NK theory, the key problem is that wage and price stickiness misaligns relative prices, including intertemporal prices (i.e. the real interest rate), and if the zero lower bound binds, then monetary policy can't correct the problem. Summers seems to want us to think that we can have permanent relative price distortions - that if monetary policy is hemmed in by the zero lower bound we'll have inefficiency forever.