Who’s afraid of the AQR?

Banks have incentives to recapitalize in socially undesirable ways and to hide losses on their balance sheets. Will the comprehensive assessment solve

Banks have incentives to recapitalize in socially undesirable ways and to hide losses on their balance sheets. Will the comprehensive assessment solve these issues by forcing significant European banks to recognize losses and to recapitalize by issuing new equity instead of deleveraging? Between January and July 2014 euro area banks have announced equity issuance of about €38 billion, of which €28 billion has currently been issued. Over 75% comes from banks in Greece, Spain, Italy and Portugal. In addition, banks issued about €14 billion of Additional Tier 1 (AT1) capital, or CoCos. Here, banks in Spain, France and Germany have been big issuers. The total of €52 billion lies below earlier predictions of €80-130 billion of required recapitalization. In addition to the strengthening of their regulatory capital, banks also reported provisions and impairments totaling up to €135 billion.

Deleveraging is socially undesirable because the resulting contraction of credit hits growth of healthy firms

If banks have to recapitalize, they prefer deleveraging over issuing fresh capital because of two market failures. Banks prefer to increase their capital ratios by deleveraging over issuing fresh capital because (1) the cost of issuing fresh capital are born by the existing shareholders due to debt overhang and (2) because issuing capital is seen as a negative signal by the market due to information asymmetry (see e.g. Marinova et al. 2014 for review of relevant literature). Deleveraging is socially undesirable because the resulting contraction of credit hits growth of healthy firms. This is not just theory: the empirical literature documents the negative effect of capital shocks on bank lending and the real economy (see e.g. Peek and Rosengren, 2000; Albertazzi and Marchetti, 2010; Jiménez et al. 2012).

Under existing regulation, supervisors can specify what capital ratio banks should have, but not in what way banks should recapitalize if they fall short of that ratio. To address the two market failures mentioned above supervisors currently have only two instruments: (1) enhance the transparency of bank’s balance sheets to reduce information asymmetry, and (2) impose tight deadlines for recapitalization which reduces the possibility to use deleveraging. The Comprehensive Assessment (CA), consisting of the asset quality review (AQR) and stress tests, should be seen in this light. By applying a uniform measure to determine the quality of banks’ balance sheets, the ECB aims to identify hidden bank losses. The limited time between the AQR, the publication of the results in the autumn and the deadline to recapitalize, stimulates problem banks to raise new capital. The deadlines to significantly improve capital ratios are too short for substantial deleveraging.

Because the stress tests are carried out on the basis of year-end 2013 figures, banks have an incentive to clean up their year-end 2013 balance sheets. To avoid capital shortfalls resulting from the CA, banks can issue fresh equity or convertible contingent bonds (CoCo’s, debt like contracts that convert to equity under certain pre-specified conditions) that count as Additional Tier 1 capital (AT1). Table 1 below shows capital and CoCo’s issuance in 2012, 2013 and 2014. Data was gathered manually from public sources.

Table 1 Capital and CoCos issuance between 2012 and 2014 (*)

* 2014 is up to and including July

|

year |

Issued capital |

Issued Coco’s |

|

2012 |

€ 17 billion |

€ 0 |

|

2013 |

€ 16 billion |

€ 6.3 billion |

|

2014 |

€ 28 billion |

€ 14 billion |

Between January and July European banks have announced to issue for about €38 billion in fresh capital and about €14 billion in CoCos. From the announced €38 billion of equity, about €28 billion has actually been issued. Compared to 2013 and 2012 capital issuance has substantially increased. On the one hand this can be explained by incentives provided by the CA. On the other hand, conditions in equity markets have also improved.

The ECB claims that since July 2013, more than €140 billion has been added in additional capital or by reducing business

In addition to the strengthening of their regulatory capital, these banks also reported provisions and impairments totaling up to €135 billion. Combining capital reinforcements and provisions, European significant banks have, since the beginning of 2014, been bolstering their balance sheets by over €180 billion. The ECB claims that since July 2013, more than €140 billion has been added in additional capital or by reducing business. Our figure is consistent with this claim. Because we do not consider deleveraging here, our numbers differ.

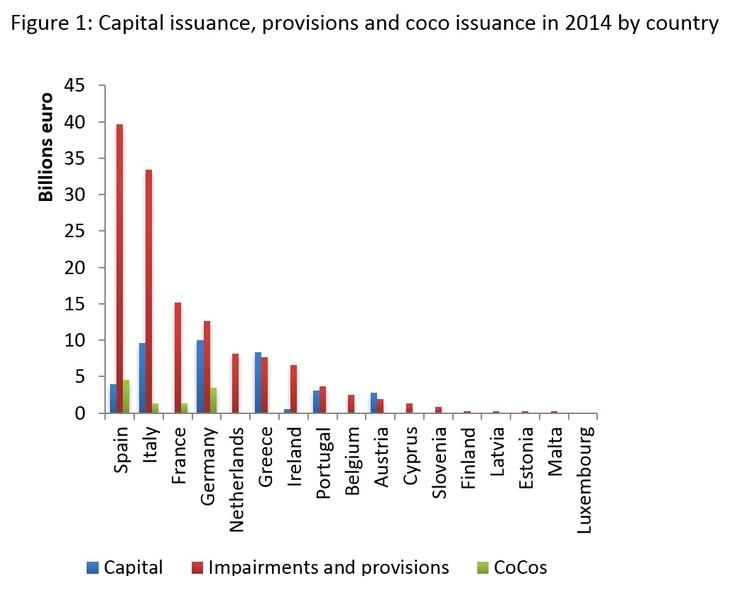

Figure 1 shows the distribution of capital issuance and impairments over countries. From the announced €38 billion of new equity, about €28 billion has currently been issued. Over 75% is from banks in Greece, Spain, Italy and Portugal. Banks in Spain, France and Germany have been big issuers of AT1 capital, or CoCos, as a way to beef up their capital ratios. The CoCo-market has been growing since last year, when banks in Spain, Italy, Denmark and Belgium launched their first CoCo -deals. This year, euro area banks have issued over €14 billion of CoCos. The same banks reported provisions and impairments totaling up to €135 billion. Compared to other banks in euro area Member States, banks in Spain and Italy have been recognizing considerable amounts of losses. One explanation is that they have anticipated on the strict(er) measures for loss-recognition as applied in the AQR.

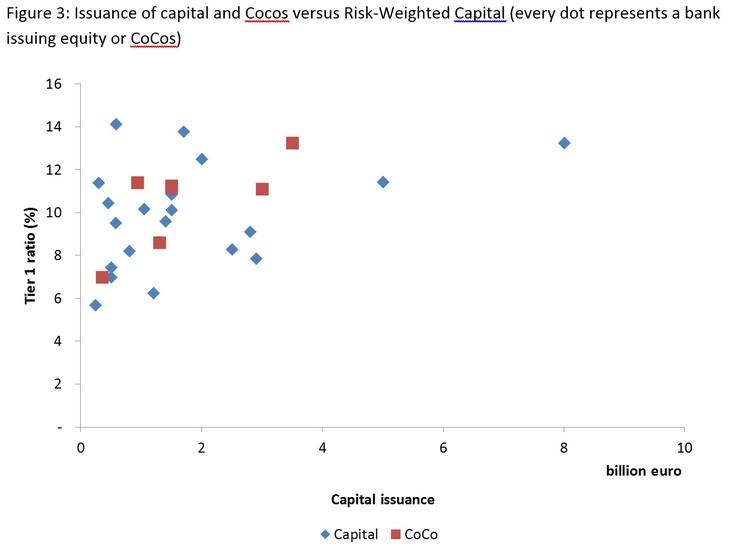

There is no clear relation between capital or CoCo issuances, and the risk-weighted capital ratio

If risk-weighted capital ratios are a sufficiently reliably proxy for the resilience of a bank, one might expect that predominantly banks with low risk-weighted capital ratios are bolstering their balance sheets. However, as the figure below suggests, there is no clear relation between capital or CoCo issuances, and the risk-weighted capital ratio. This might imply that the risk weighted capital requirements are not a reliable indicator of the banks’ resilience. Since banks are increasing their non-risk-based leverage ratios, the CA addresses this issue partly.

Conclusion

Banks might be be healthier than predicted or the stress test may be less strict than expected

The AQR has clearly provided banks with an incentive to clean-up their balance sheet and bolster the level of regulatory capital by issuing equity and AT1 capital. The amount of already issued and announced issues seems limited compared to earlier predictions of required recapitalization for euro area banks: €52 billion against predicted recapitalizations of €80-130 billion. One conclusion could be that European banks are healthier than predicted earlier. It could also mean that the stress test is less strict than expected. Only time will tell.

Read more on AQR

Fact of the week: Only 8% of banks says they will need to raise capital after AQR