Will a UK welfare reform ease the UK's EU negotiation?

In a speech on 22 June 2015, UK David Cameron pointed at a number of possible changes that could be made to the UK's tax credit system. Why is th

In a speech on 22 June 2015, UK Prime Minister David Cameron pointed at a number of possible changes that could be made to the UK’s tax credit system. The UK’s tax credit system is an arrangement whereby some taxpayers (families and individuals on low income) can deduct a certain amount of money from the tax they owe to the state (although you do not have to actually pay any tax to receive the tax credit: the name is misleading). The Labour government introduced tax credits in the 1990s.

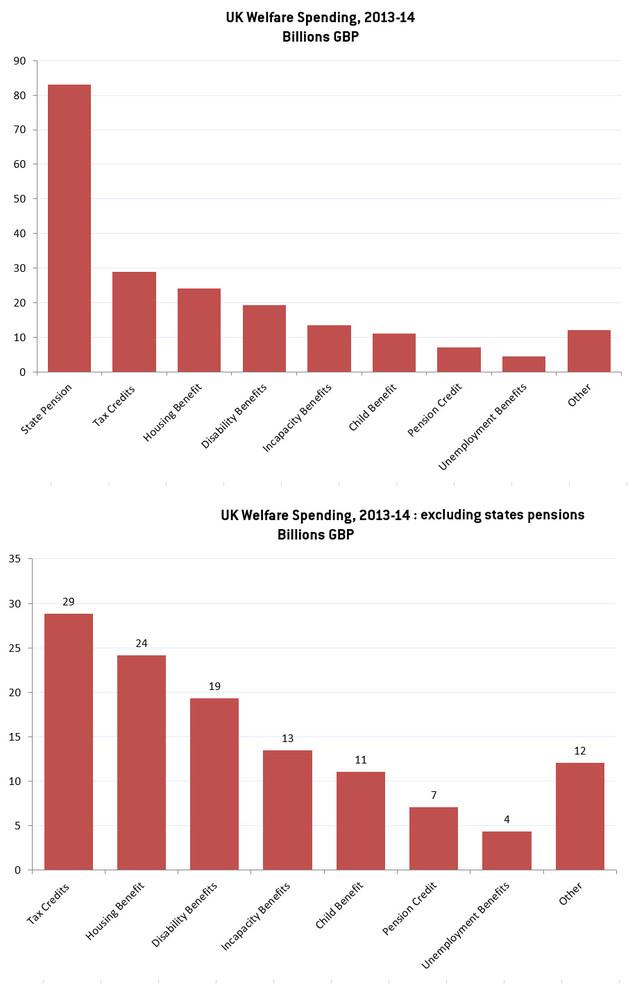

Why is the UK government suddenly thinking of reforming this system? The first immediate reason is the UK government’s official aim of cutting public spending. In an article in the Sunday Times on 21 June 2015, Chancellor of the Exchequer George Osborne and Secretary of State for Work and Pensions Iain Duncan Smith outlined a plan to reduce welfare spending by £12 billion a year. A quick look at UK welfare spending shows that tax credits (most importantly Child Tax Credit and Working Tax Credit) are an obvious area for attention, since cuts to state pensions have been ruled out.

Source: Department for Work and Pensions (DWP)

Incidentally, tax credits are regularly the subject of criticism, especially from the Conservative Party since the system was introduced under a Labour government.

David Cameron purported in his speech that the current UK welfare system amounted to a ‘merry-go-round’: “People working on the minimum wage having that money taxed by the government and then the government giving them that money back – and more – in welfare.” He hinted at three measures in particular:

- Increasing the minimum wage: “The minimum wage is rising to £6.70 per hour from October 2015 – the largest real-terms increase since the financial crash and is forecasted to rise to £8 by 2020 on current projections.”

- Increasing the tax-free amount of wages: “It is why we have increased the amount you can earn without paying tax, saving a typical taxpayer £825 a year, and it’s why we will take 1 million out of tax by increasing the tax free threshold to £12,500.”

- Free childcare: “Add the 30 hours of free childcare we will introduce for working families, and rewards from work, will be even stronger.”

What David Cameron does not say explicitly is what would happen to the tax credits in their present form. The media clearly expects an attack on the current system, but specifics are lacking: The Guardian reported an ‘assault’ on tax credits; the BBC pointed at Cameron’s ambition to “end welfare merry-go-round.” The UK prime minister is clearly signalling profound changes to the tax credit system, but it is unclear how far he is ready to go in reforming it or perhaps more radically removing it altogether.

But this reform could also have important implications for the UK’s EU renegotiation and impending referendum – and this could be the second motivation for reform.

The most contentious issue among the otherwise vague list of demands for EU reform formulated by the UK government is that concerning EU freedom of movement rules. Tellingly, this demand was included in the chapter “Controlled immigration that benefits Britain” in the Conservative Party’s 2015 Manifesto, but not in the chapter “Real change in our relationship with the European Union.” The Conservative Party’s demands read: “We will negotiate new rules with the EU, so that people will have to be earning here for a number of years before they can claim benefits, including the tax credits that top up low wages. Instead of something-for-nothing, we will build a system based on the principle of something-for-something.”

The ability of non-UK citizens to access tax credits that top up low wages was therefore most clearly spelled out. In the event of a profound reform of the UK’s tax credit system – in particular if the UK government decides to completely dispose of the tax credit principle – this would de facto remove the most contentious demand on the EU negotiation table. In November 2014 and again in January this year, German chancellor Angela Merkel for instance most clearly voiced her opposition to any change to the current rules on the freedom of movement, even at the expense of an eventual Brexit. But if people living in the UK, regardless of their citizenship, were no longer in principle to claim tax credits, why would the UK government ask for a change in the EU freedom of movement’s rules? The list of the UK’s negotiations demands would be easier to deal with, if very vague.

In that sense, side-stepping the free movement issue via tax credit reform would bring today’s negotiation much closer to that in 1975, the year of the UK's previous EU membership referendum (analysed in a recent Bruegel Policy Contribution). In 1975, British Prime Minister Harold Wilson formulated a list of demands – including changes to the common agricultural policy, retention by UK Parliament of some powers and fairer methods of financing the EU budget – that avoided going into the specifics. The UK renegotiations of 1975 brought mostly cosmetic changes, but the vagueness of the original demands allowed these cosmetic changes to be presented as successes during the referendum campaign. The situation could take a similar path today: removing the UK’s original request for EU Treaty changes on the freedom of movement would leave only a few vague items on the UK’s list of demands (see 2015 Conservative Party Manifesto): ‘reform the workings of the EU’, ‘reclaim power from Brussels’ and ‘safeguard British interests in the Single Market’. David Cameron’s plans to reform the UK’s tax credit system will therefore be an unexpected critical domestic component of the UK government’s EU negotiation stance.

[1] I would like to thank Stephen Gardner for his help in conceiving this blog and Thomas Walsh for compiling the chart’s data.