One market, two monies: the European Union and the United Kingdom

So far, having more than one currency in the EU has not undermined the single market. However, attempts to deepen integration in the banking, labour

The issue

Access to the single market is one of the core benefits of the United Kingdom’s membership of the European Union. A vote to leave the EU would trigger difficult negotiations on continued access to that market. However, the single market is not static. One of the drivers of change is the necessary reforms to strengthen the euro. Such reforms would not only affect the euro’s fiscal and political governance. They would also have an impact on the single market, in particular in the areas of banking, capital markets and labour markets. This is bound to affect the UK, whether it remains in the EU or not.

The policy challenge

A defining characteristic of the banking, capital and labour markets is a high degree of public intervention. These markets are all regulated, and have implicit or explicit fiscal arrangements associated with them. Deepening integration in these markets will likely therefore require governance integration, which might involve only the subset of EU countries that use the euro. Since these countries constitute the EU majority, safeguards are needed to protect the legitimate single market interests of the UK and other euro-outs. But the legitimate interest of the euro-area majority in deeper market integration to bolster the euro should also be protected against vetoes from the euro-out minority.

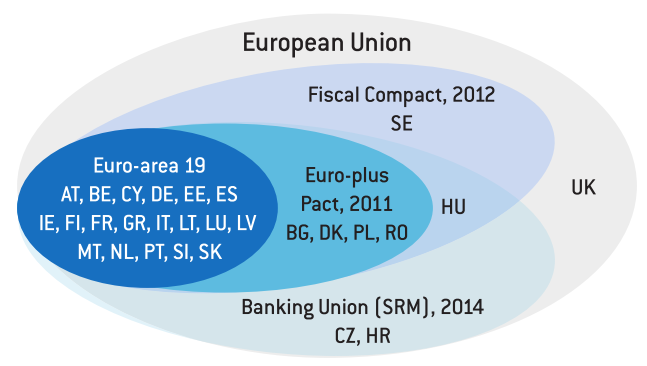

Participation of euro and non-euro EU countries in intergovernmental arrangements to strengthen EMU

Source: Bruegel. SRM = Single Resolution Mechanism.

In the late 1950s, many European countries shared the goal of market integration but those able to choose freely split into two groups. Some, wishing for more than market integration, joined the European Economic Community (EEC): an ‘ever closer union’ with common institutions and policies. Others, led by the United Kingdom, joined the European Free Trade Association (EFTA) and wished only for market integration.

The UK joined the EEC in 1973 (and decided to remain in 1975)1 because it judged that staying outside would hurt its economic interests, not because of a change of view on the broader aims of European Integration. Most other EFTA members eventually joined the EEC.

In the 1980s, the UK government was one of the staunchest supporters of the single market that aimed to complete the common market’s objective of free movement of goods, persons, services and capital. But in line with its divided view on integration, the UK rejected the ‘one market, one money’2 logic advocated at the time in support of a single currency, because it considered that the single currency would create common institutions and policies amounting to a huge step towards ‘ever closer union’.

Since the decisions were taken to complete the single market and create a monetary union, there have been three major developments in European economic integration. First, the single market has advanced but is unfinished, with significant remaining barriers to free movement inside the EU. Second, the euro was introduced but the original design has proved fragile and additional institutions and policies have been introduced to address the causes of the euro crisis. The euro also remains an unfinished construction. Third, the EU has grown to 28 members, with increased heterogeneity in economic, social and political conditions.

These developments lie at the heart of UK prime minister David Cameron’s November 2015 letter to European Council president Donald Tusk asking for “a new settlement for the United Kingdom in a reformed European Union” (Cameron, 2015). His four key demands3 are:

- In order to improve competitiveness, the EU should “do more to fulfil its commitment to the free flow of capital, goods and services”, ie it should complete the single market.

- Regarding the other single market area, the free flow of persons, there should be limits to social benefits in order to “reduce the flow of people... coming to Britain from the EU”, a clear reference to the situation created by the EU enlargements to low-income countries from central and eastern Europe.

- It is legitimate for euro members to take the necessary measures to sustain the monetary union and it matters to Britain that the project succeeds. “But we want to make sure that these changes will respect the integrity of the single market, and the legitimate interests of non-euro members”.

- There should be a recognition that the UK position in the EU is special by ending “Britain’s obligation to work towards an ‘ever closer union’”.

They raise three questions: (1) How can the single market be deepened in line with this vision? (2) How would measures to sustain the monetary union affect the single market? (3) How should the relationship between euro and non-euro countries be managed to ensure the integrity of the single market?

Irrespective of whether the UK stays in the EU or leaves, these questions must be tackled. In particular, after an exit from the EU, the UK would want to retain access to the single market. The exit negotiations would certainly focus on that access and the conditions attached. Changes to the single market and its governance – for instance to strengthen Economic and Monetary Union (EMU) – would affect all countries that are part of the single market, whether they belong to the EU or not. But they will affect EU and non-EU countries differently in terms of governance. For EU members, the governance mechanisms would be mostly based on the EU treaties, but the UK outside would have to rely on intergovernmental agreements.

Finally, no federation or confederation remains static in governance terms. The EU will be continuously subject to reforms and changes. This complicates the definition of the relationship between the euro area and the single market because the euro area’s eventual shape is far from being agreed. We consider likely future developments in euro-area governance and how their impact on non-euro area and non-EU countries can be managed. As a blueprint for future governance developments, we use the Five Presidents’ Report issued by European Commission president Juncker (2015), though we recognise that it leaves many important questions unanswered.

The Single Market then and now

The common market and subsequently the single market have been the cornerstones of European economic integration.

When the UK joined the EU, the common market essentially meant free movement of goods and workers. In the former case, tariffs and quotas had been eliminated but many non-tariff barriers were still in place. But free movement of goods also meant common competition, trade and agriculture policies. The UK had to adopt these policies, despite some reticence about loss of sovereignty.

Free movement of workers had also been technically achieved by 1973 when the UK joined, but did not translate into much labour mobility between EU countries. In addition to cultural obstacles, economic and social conditions were sufficiently similar across EU countries to result in little desire or necessity to move.

The single market programme that started in the mid-1980s sought to remove hundreds of remaining barriers to the free movement of goods, persons, services and capital. Non-tariff barriers to goods were largely eliminated as were capital controls, resulting in substantial capital movements. Further barriers to the free mobility of workers were also removed but intra-EU migration flows remained low, despite the accession in the 1980s of the lower-income countries Greece, Portugal and Spain.

The one area in which there was little progress was services. The Services Directive (2006/123/ EC) eventually took effect at the end of 2009, but left many remaining barriers because of fears of unfair wage competition, resulting from the accession of ten lower-income central and eastern European countries. In addition, the Services Directive did not cover regulated network services, such as transportation, telecommunications or energy. For these activities, the creation of a single market would require a common EU philosophy about regulation, if not the replacement of national regulators by single EU regulators.

A not-so single market

The EU is characterised by differentiated levels of integration for different countries and different policy areas, but the UK stands out as the most differentiated4.

The 1991 Maastricht treaty did not affect the EU rules on free movement of goods, persons, services and capital, but it did introduce a permanent derogation (‘opt-out’) from monetary union for Denmark and the UK and a temporary, but not time-limited derogation to fulfil the conditions to adopt the single currency for all other EU countries.

The Maastricht treaty also introduced differentiation in social policy. The UK received an opt-out from the social protocol annexed to the treaty, though this ended in 1997 when the UK joined the other EU countries in signing the Amsterdam treaty, which incorporated the social protocol in the EU treaty.

The Amsterdam treaty also incorporated the provisions of the Schengen Agreement abolishing border controls between EU member states. From this, the UK and Ireland received both an opt-out (a permanent derogation from the Schengen rules) and an opt-in (the possibility to participate in Schengen if participating states agree)5. The Schengen rules have clear implications for the free movement of goods and people, and are thus an element of differentiation in the single market.

One market, one money?

The predominant view in continental Europe at the time of Maastricht was that the single currency was the natural, perhaps even indispensable, complement to the single market, because of the transaction costs of different currencies and/or because of the potential political consequences for the single market of competitive devaluations6. Most British and American economists, however, considered that “the economic justification for [the one market, one money] view is dubious” or even that it “has no basis in either theory or experience”7.

After the launch of the euro in 1999 and until the onset of the euro-area crisis in 2010, the sceptical view seemed to prevail over the ‘one market, one money’ view. There were no complaints by euro-area countries that non-euro countries resorted to competitive devaluations, and there were no complaints in non-euro countries that euro-area countries benefitted from a competitive advantage in the single market because of the euro8. Before the euro-area crisis, therefore, there seemed to be no problem in operating the single market with multiple currencies.

Will euro-area reform change the nature of the single market?

The crisis demonstrated painfully that the Maastricht single currency setup was incomplete. In response, various governance reforms have been made, within existing treaties and through intergovernmental agreements. These mainly concern fiscal rules and have raised important issues for the relationship between euro-area and non-euro area countries9. However, these governance changes have only marginally impacted the single market.

But the post-crisis debate went further and argued that a ‘genuine EMU’ needs, as well as monetary union, an economic union, a banking union, a fiscal union and ultimately probably a political union10. The Five Presidents’ Report makes concrete proposals on how to move forward, and the banking union has been already set in motion. These proposals have direct implications for the single market in terms of banking, capital markets and labour markets.

Banking

The only area of the single market so far affected by the political deepening of EMU is banking markets. UK interests in this area are obviously very important. After the creation of the euro, there was significant banking integration through large wholesale banking flows within EMU. However, the crisis led to a substantial re-fragmentation along national lines (Sapir and Wolff, 2013). The integration of the banking policy framework was a direct response to the fragmentation and the consequence of monetary union that made a single central bank the liquidity provider to a banking system with decentralised supervision.

A successful banking union should eventually lead to a more integrated euro-area banking market, with fewer national banks and greater cross-border banking. But such a development raises significant questions for the single market for banking, from both economic and governance angles. Will more-integrated euro-area banks fragment the EU banking market by deepening the separation from non-euro area banking systems? How will new euro-area institutions act? Will there be new EU regulatory initiatives with the primary aim to strengthen the euro-area banking market? The overall question that must be addressed is how far such initiatives would be detrimental to the single market for banking11.

Capital markets

Capital markets union is a whole-EU project that is being rolled-out within the single market policy framework12. Clearly, from an economic point of view, capital markets without the UK and the City of London are inconceivable. At the same time, the economic rationale for deepening cross-border capital markets is particularly strong in the monetary union in order to achieve risk sharing (Bank of England, 2015).

What would it take to achieve greater capital markets integration, and to what extent is political stability important for financial integration? The euro in its early phase boosted financial integration across the euro area, even though some of this led to bubbles. But with the emergence of political break-up risks, financial fragmentation increased substantially at the height of the crisis, only to reverse more recently.

Beyond over-arching political risks, regulatory harmonisation (such as corporate insolvency, taxation or financial product regulation) can increase cross-border financial flows. The question is then whether a subset of EU countries or even the euro area will advance without the UK and to what extent that would be an obstacle to the economic development of the UK and its financial system. Deeper euro-area capital markets do not per se undermine the role of financial centres outside the area. However, for example, a European regulation that limits remuneration in the hedge-fund industry or in the insurance sector, would affect the City of London. Whether this happens or not is largely a question of politics and governance and not of the inherent economic driving forces of monetary union.

On the governance side, a differentiation is already becoming visible. The Five Presidents’ Report views the integration of capital markets as a priority for all EU countries “but... particularly relevant to the euro area” because EMU needs to “strengthen private sector risk-sharing across countries”13. This could mean that euro-area countries should strive to use EU single market rules to integrate capital markets, but that in case of insurmountable obstacles they should not hesitate to use other means, such as intergovernmental agreements. The Five Presidents’ Report even highlights the main likely obstacle when it suggests that integrating capital markets “should lead ultimately to a single European capital markets supervisor”. This would likely be a red line for the UK government14.

Labour markets

The Five Presidents’ Report raises the possibility of differentiating EU labour mobility. It calls for a “push for a deeper integration of national labour markets by facilitating geographic and professional mobility, including through better recognition of qualifications, easier access to public sector jobs for non-nationals and better coordination of social security systems”. The current refugee crisis is fast changing the political dynamics in this area.

One of the UK’s core demands is to end equal social security treatment. Other countries seem to be somewhat open to this, partly because of the increased heterogeneity of economic conditions in the EU after enlargement. Obviously, welfare tourism should be prevented, even though the evidence is not strong that this is a real problem (Giulietti, 2014). The main issue is whether unequal treatment of domestic citizens and other EU nationals would undermine the integrated labour market. We would argue that it would, because foreigners would be disadvantaged in labour market participation terms relative to domestic citizens. To maintain the integrity of the single market for labour, the challenge is to limit fraudulent behaviour or welfare tourism, while retaining the equal treatment principle.

Introducing discrimination in the treatment of domestic citizens versus other EU nationals would limit EU labour mobility, with negative effects for resource allocation and EU growth prospects. It would also most likely require a revision of the EU treaty, which would have to be done in a way that left the equal treatment principle untouched for the euro area, where labour mobility is essential on efficiency grounds and as a shock absorption mechanism.

In fact, the euro area needs more cross-border labour mobility, not less. This might require even deeper integration of labour market policies and the portability of at least some welfare benefits (Claeys et al, 2014). Differentiation of labour market integration could thus come both from the side of (some) euro outsiders and from euro area members. Both would require treaty change.

How to manage frictions between deeper integration of monetary union and the single market?

We have shown that there are few if any genuine economic forces arising from monetary union that necessarily drive a wedge between euro and non-euro countries in the single market. However, monetary union requires a deeper level of economic integration, in particular in banking, financial markets and labour markets15, a defining feature of which is that all are subject to significant regulatory, supervisory and even implicit and explicit fiscal arrangements. The agenda of deeper EU integration will therefore entail various regulatory and institutional approaches, as well as measures in pursuit of fiscal and political integration.

By 2025, the time horizon for completing EMU envisaged by the Five Presidents’ Report, there are two possible scenarios: one in which the UK (if still an EU member) is the only country outside the euro, and one in which other countries have also not joined the euro. The UK certainly stands out as the only country that has not signed the three post-crisis intergovernmental agreements to strengthen EMU (see the figure on the front page). But that does not mean that all the other countries will join the monetary union in the next decade. This will largely be a political question, but a better functioning EMU will surely increase the pull of monetary union.

The question of the relationship between the UK and Denmark and the euro area is, in a sense, the easiest one. Both have a euro opt-out and could not have anticipated that future changes to the single market would be needed to strengthen EMU. It seems normal, therefore, that the countries that now wish to introduce such changes, either through new EU rules or through intergovernmental agreements, ensure that they do not negatively impact the permanent opt-out countries.

Other EU countries agreed to join the euro in due course when they joined the EU. This puts a greater onus on them to accept the changes necessary to reinforce EMU. However, it would be fair that they are fully associated with the reform process in the euro area, even while waiting to join.

But it is not only the countries currently outside the euro that need safeguards to protect their legitimate single market interests. The majority also needs protection to ensure that their legitimate efforts to strengthen EMU, including where necessary by deepening the single market, will not be vetoed by the non-euro minority. This boils down to creating mechanisms to protect both the minority against the tyranny of the majority and the majority against the tyranny of the veto.

Agreement should be reached on this within the existing treaty framework. Giving the UK (and other non-euro members) a veto right would not be any more appropriate than the euro countries having the right to disregard the opinions of their non-euro counterparts. This mutual guarantee would have to apply to EU laws as well as the actions of existing institutions.

It is up to lawyers and politicians to find the best ways to achieve this. Currently, there seem to be adequate measures in place to protect outsiders. For example, the UK filed a complained against the European Central Bank about its treatment of clearing houses and won the case before the European Court of Justice (ECJ)16. And the UK has won safeguards in banking union matters through the European Banking Authority.

Nevertheless, the day-to-day governance of monetary union currently takes place largely inside the Eurogroup, which is causing friction. We have argued elsewhere that the relationship between the ECOFIN council and the Eurogroup should be re-thought (Pisani-Ferry et al, 2012). For example, it would be a strong symbol of good-will for Eurogroup meetings to follow the ECOFIN, instead of the other way around, as currently.

References

Asdrubali, P., B. E. Sorensen and O. Yosha (1996) ‘Channels of interstate risk sharing: United States 1963-1990’, The Quarterly Journal of Economics 111 (4): 1081-1110

Baldwin, R. E. (2006) In or out: does it matter? An evidence-based analysis of the Euro's trade effects, Centre for Economic Policy Research

Bank of England (2015) ‘A European Capital Markets Union: Implications for growth and stability’, Financial Stability Paper No.33, February

Bean, C. R. (1992) ‘Economic and monetary union in Europe’, The Journal of Economic Perspectives, 6(4): 31-52

Cameron, D. (2015) ‘A new settlement for the United Kingdom in a reformed European Union’, letter to European Council president Donald Tusk, 10 November, available at https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/fi…

Claeys, G., Z. Darvas and G. Wolff (2014) ‘Benefits and drawbacks of European Unemployment Insurance’, Policy Brief, 2014/06, Bruegel

European Commission (1990) ‘One market, one money. An evaluation of the potential benefits and costs of forming an economic and monetary union’, European Economy, Vol.44: 347

Feldstein, M. (1997) ‘The political economy of the European economic and monetary union: political sources of an economic liability’, The Journal of Economic Perspectives, Vol 11(4): 23-42

Giulietti, C. (2014) ‘The welfare magnet hypothesis and the welfare take-up of migrants’, IZA World of Labor 2014: 37

Hill, J. (2015) ‘Presentation of Green Paper on Capital Markets Union’, SPEECH/15/4494, European Commission, 24 February

HM Government (2014) Review of the Balances of Competences between the United Kingdom and the European Union, available at https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/review-of-the-balance-of-com…

Juncker, Jean-Claude, in close collaboration with Donald Tusk, Jeroen Dijsselbloem, Mario Draghi, and Martin Schulz (2015) ‘Completing Europe’s economic and monetary union’, Five Presidents’ Report, June

Mourlon-Druol, E. (2015) ‘The UK’s EU Vote: The 1975 Precedent and Today’s Negotiations’, Policy Contribution 2015/08, Bruegel

Pisani-Ferry, J., A. Sapir and G. Wolff (2012) ‘The messy rebuilding of Europe’, Policy Brief 2012/01, Bruegel

Piris, J. (2015) ‘Which Options Would be Available to the United Kingdom in Case of a Withdrawal from the EU?’ CSF-SSSUP Working Paper No.1

Piris, J. (2016) ‘If the UK votes to leave: The seven alternatives to EU membership’, Policy Brief, Centre for European Reform

Santos Silva, J.M.C and S. Tenreyro (2010) ‘Currency Unions in Prospect and Retrospect’, CEP Discussion Paper No. 986, Centre for Economic Performance

Sapir, A. and G. Wolff (2013) ‘The neglected side of banking union: reshaping Europe’s financial systems’, Policy Contribution presented at the informal ECOFIN in Vilnius on 14 September.

Stubb, A. C. G. (1996) ‘A categorization of differentiated integration’, Journal of Common Market Studies, 34(2): 283-295

Van Rompuy, Herman, in close collaboration with José Manuel Barroso, Jean-Claude Juncker and Mario Draghi (2012) Towards a genuine economic and monetary union, European Council, Brussels

Véron, N. and G. Wolff (2013) ‘Capital markets union: a vision for the long term’, Policy Contribution 2015/05, Bruegel

However, as we have argued, the fault-lines between the euro area and the single market could widen, which would require a more robust arbitration mechanism. Piris (2015) proposes to entrust this to the ECJ, but there could be other forums. David Cameron’s proposal to give national parliaments a veto right is problematic, however, because it would change the nature of the union and potentially slow down euro-area integration.

Arbitration would hardly solve the deeper issues, however. In the three single market areas we have discussed, we see at least some situations in which the current EU treaty would not provide adequate safeguards. This concerns both the deepening of the euro area and the stepping back of the UK from some already-undertaken integration steps, most notably in migration.

In terms of deeper euro-area integration, one could imagine further intergovernmental agreements or even a new euro-area treaty. The question then is what legal safeguards could be put in place to prevent such a euro-area treaty from unduly damaging the UK’s single-market interests.

As far as situations in which the UK might wish to opt out of EU legislation relating to labour mobility are concerned, and especially if the UK decided to leave the EU, we would imagine it to be possible that a new legal status for the UK could be negotiated17. This status could give access to the single market for goods but be much more restrictive for labour mobility. However, access to the single market for (financial) services would be a core issue of the negotiations and would most certainly be used as a bargaining chip to limit the reduction in labour mobility18.

In conclusion, having the euro and other currencies has not undermined the single market so far. But there could be attempts to deepen the single market in the euro area in order to increase its resilience, which will create a need for new regulations, new or strengthened institutions and, ultimately, greater democratic legitimacy mechanisms. These developments could, but would not necessarily, affect the functioning of the EU single market. Soon rather than later, the euro-area majority, and the UK (and other outs) must agree on how to protect their respective interests. Without such agreements, significant economic conflicts could emerge from governance decisions and policy divergence in a deepening single market in the euro area. This would be damaging for all EU countries.

Finally, a UK exit from the EU would not make the potential problems we have discussed disappear. Geography dictates that the UK’s relationship with the EU single market would remain paramount. With respect to its participation in the single market, all that the UK would achieve by leaving the EU would be to weaken its position to influence European regulations, institutions and politics.

We thank colleagues, as well as Ian Harden and Helen Wallace, and a number of policymakers, for their comments on earlier drafts of this paper. Remaining errors are our own.