Are central bank(er)s still credible?

Both the Fed and the ECB have managed to remain credible since the financial crisis, but their credibility levels have evolved differently. Since infl

This post is available in German on Makronom.

As policymakers prepare to go to unexplored lengths in using unconventional monetary measures (Gürkaynak and Davig 2015; Roubini 2016; Demertzis and Viegi 2010), the key to the effectiveness of monetary policy remains, as always, 'expectations': what people believe the future holds and the confidence they have in a central banks' ability to achieve their objectives. In other words, credibility. When markets have trust in central banks' ability to deliver price stability, the central bank needs to do less to deliver it. And conversely, without credibility more aggressive action is needed to achieve the same objective.

Credibility becomes more important in times of high uncertainty (Demertzis and Viegi 2010). This is because it becomes less about specific policies, and more about confidence in policymakers’ ability to manage uncertainty (Drazen and Masson 1994; Posen 2010).

When markets have trust in central banks’ ability to deliver price stability, the central bank needs to do less to deliver it.

Years of successful inflation performance prior to the financial crisis allowed central banks in the US and the euro area to become highly credible. This was manifested in the extent to which long term expectations were anchored to inflation targets.

But since the start of the financial crisis, inflation has become much more volatile in both the US and the euro area, reflecting persistently high uncertainty (Yellen March 29, 2016). And for the past couple of years it has been on a persistent declining path. Policymakers have reacted, and interest rates are now at the zero lower bound, which has raised doubts about the central banks' ability to control inflation. Are central banks still credible?

A measure for credibility

How can credibility be measured? The way to capture it is by looking at how closely inflation expectations match the central bank's inflation target (Demertzis et al 2012). The closer the two are for sustained periods of time, the more credible a central bank. However, inflation itself is also crucial to credibility. If inflation deviates from the target for long periods, then expectations lose their capacity to convey views on credibility.

It takes repeated successes for an institution to build up this stock that will allow it to establish credibility.

Two features are crucial when measuring credibility: first, identifying the stock of credibility that is deemed sufficient. In our measure, which ranges from 0 to 1, we identify this at 0.9. Second, it is crucial to recognise that it is through sustained failures that agents lose faith in an institution's ability to deliver results. And the other way around: it takes repeated successes for an institution to build up this stock that will allow it to establish credibility.

What kind of expectations are relevant?

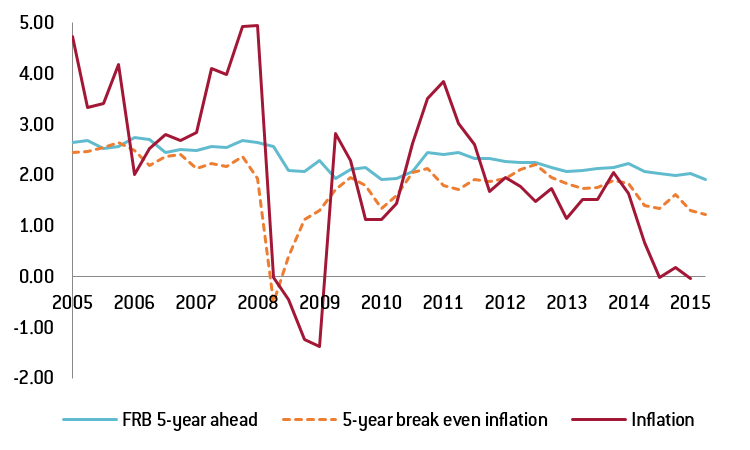

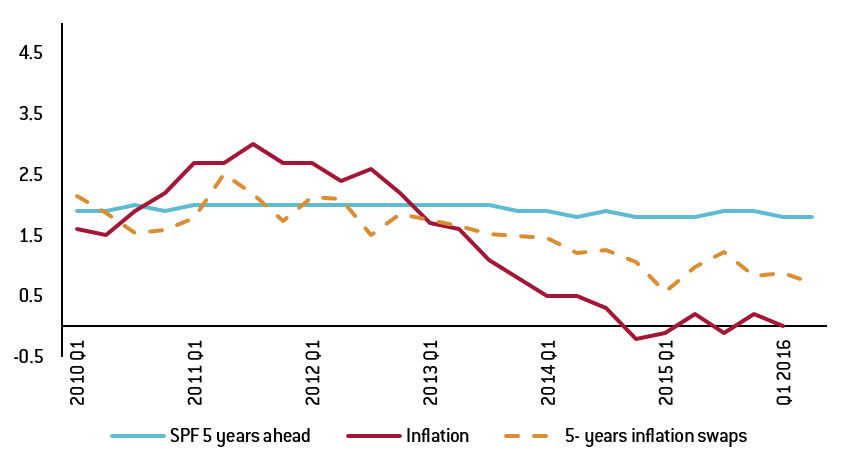

We apply here survey expectations to proxy policy makers’ credibility. If these expectations are de-anchored, then trust in their ability to manage the system is lost. However, it is important to acknowledge that recently a pronounced wedge has emerged between survey and market expectations measures (Christensen and Lopez 2016), in both the US as well as the euro area.

Figure 1a: US - Inflation Expectations, Survey vs Markets

Source for figures 1a and 1b: FRB, Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia, FRED Federal Reserve Bank of St.Louis, ECB and Thomson Reuters

Figure 1b: Euro area - Inflation Expectations, Survey vs Markets

As the two series diverge, this signals that confidence is starting to wane. But also, the wedge may very well be a reflection of increased uncertainty. Market expectations are quicker to follow actual inflation (even at longer horizons) as they attempt to also capture perceptions about risk and therefore hedge against them.

Survey expectations on the other hand, reflect an opinion about inflation reaching its target in the relevant horizon and are arguably more a measure of policy makers’ ability to deliver. Nevertheless, we need to understand better the difference in information these measures convey, as well as why they are diverging.

The US: credibility gained, credibility maintained

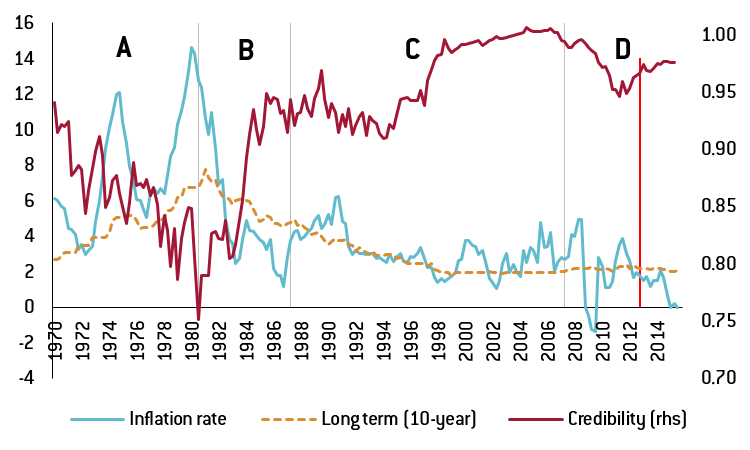

Based on a commonly agreed narrative about US monetary policy history (Goodfriend and King, 2005; Goodfriend 1993, 2005, 2007), we identify four distinct periods in its inflation history since the early 1970s (figure 2):

- Period A: period of Great Inflation ending with Paul Volker's appointment as chairman of the Fed (1980). This comprised of the two oil crises and both high and volatile inflation rates.

- Period B: Volker's disinflation period, ending in 1987. During this period inflation fell dramatically, at substantial cost to employment and growth, but there were also important gains in credibility.

- Period C: Chairman Alan Greenspan is appointed and the period is identified with a Great Moderation. This is the period where the Fed effectively established its credibility.

- Period D: coinciding with the start of the financial crisis (2007) and made up of what the IMF calls the Great Recession (2007-2009), the years of quantitative easing (QE1-3) and the recent years of very low inflation. Chairman Ben Bernanke was appointed just over a year before this period at the start of 2006.

Figure 2: Credibility in the US

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia (CPI 10-year ahead inflation expectations) and authors' calculations. Credibility threshold at 0.9.

A: Great Inflation — B: Volcker's Dininflation — C: Great Moderation — D: Great Recession — Red line: Start of QE

During most of the 1990s and until 2007, the Fed enjoyed full credibility, as shown by the measure for credibility stocks in figure 2 (blue line). With the start of the crisis, this measure started to decline, but started improving again between QE2 and QE3. We interpret this to mean that:

- the initial level of high credibility implies that despite its fall expectations had not been in any danger of being de-anchored (since it remained above 0.9 throughout the crisis), and

- three applications of quantitative easing have succeeded in reversing the declining trend in the stock of credibility.

The euro area: can high credibility be sustained?

The history of the euro area is much shorter than that of the US. Since 1999, inflation in the euro area has been much lower in member states compared to historical levels, and also significantly lower than that inflation levels achieved by the Bundesbank. An average inflation rate of between 2 and 2.5 per cent throughout the first eight years allowed the ECB to establish high credibility.

Since mid-2007, the euro area has been subjected to two crises, the financial crisis originating in the US, and the European sovereign debt crisis (end of 2009). From mid-2007 onwards, inflation became much more volatile, even if on average it was still at similar levels.

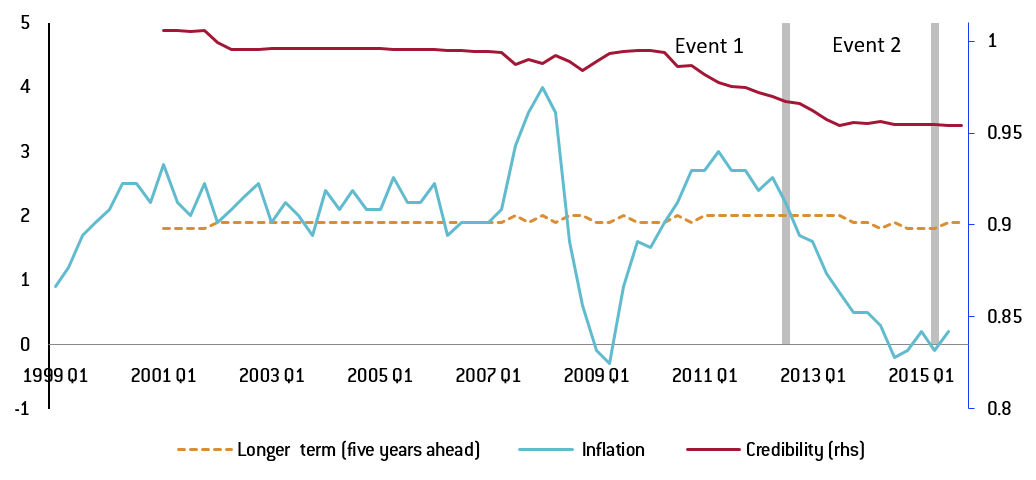

Figure 3: Credibility in the euro area

Source: ECB, (CPI inflation and SPF 5- year ahead inflation expectations), and authors' calculations. Credibility threshold at 0.9.

Events: 1. "Whatever it takes": speech by Mario Draghi — 2. Start of QE

Credibility levels, as shown in figure 3 (blue line), did not suffer until mid-2010, right after the start of the sovereign debt crisis. Credibility started to fall in mid-2010, but inflation expectations and credibility stabilised around mid-2013, after the "whatever it takes" speech by President Draghi and in anticipation of quantitative easing.

Credibility in Europe has stabilised but, unlike the US, it has not returned to previous levels.

Since then credibility has stabilised but, unlike the US, it has not returned to previous levels. Importantly, during the crisis it remained above the 0.9 mark, which indicates that expectations were never under a serious threat of being de-anchored. But can this be sustained if inflation remains at such low levels for prolonged periods of time? Already market measures of inflation expectations appear to be de-anchored. Moreover, can monetary policy alone help increase inflation or have we seen all the benefits to be had through unconventional measures?

The US and the euro area: a tale of two approaches

Inflation performance in the US and the euro area since 2007 has been remarkably similar (with a correlation of 0.84). And actually both the US and the euro area are now at around zero inflation. However, in the US there is an expectation that normalisation of monetary policy is the next big step, even if its precise timing remains unknown. In the euro area, by contrast, there is both a sense of needed action coming too late and actually not achieving much (Kang et al 2016; Ligthar and Mody 2016).

In the euro area, there is both a sense of needed action coming too late and actually not achieving much.

Two factors could account for this difference. First, a much more effective resolution of unproductive debt in the US earlier in the crisis has allowed banks to resolve non-performing loans and demand for credit to follow. And second, the current state of macroeconomic policy mix in the euro area has shifted almost the entire burden of stimulating demand to monetary policy. Overextending its reach has been necessary in the absence of other policy actions, but does not insulate the ECB's credibility from the effects of inadequate macroeconomic management.

Conclusion

Both the Fed and the ECB appear to have been effective in the way they have applied policy during the financial crisis. Based on surveys, market still believe that, given time, inflation will return to the level consistent with price stability. However, the environment in which the two have operated is quite different. Broad macroeconomic policy in the euro area has only recently reduced unemployment, and at a low pace. It has also disappointed in terms of growth. This alone is enough to affect the ECB's ability to stimulate aggregate demand, and prevent it from achieving its inflation objective.