The Trump market rally conundrum

What’s at stake: Since Donald Trump’s election in November, the US stock market has been on an unabated rally. The Dow Jones Industrial Average powere

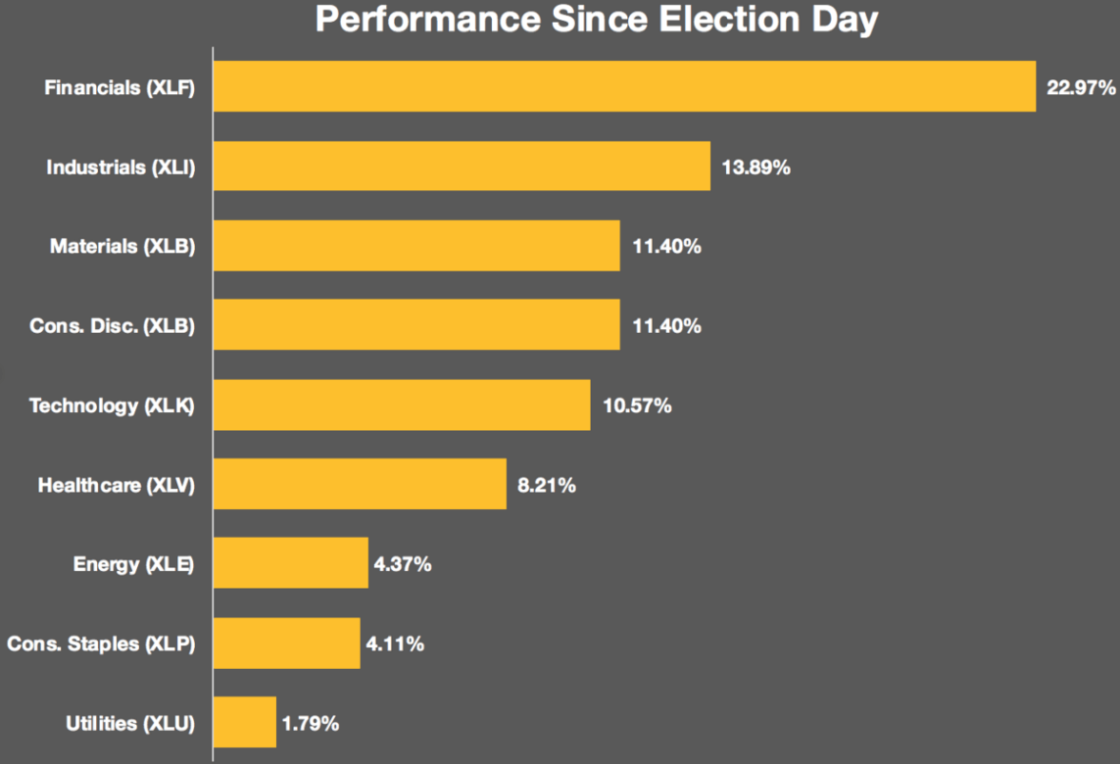

On Vox, Jim Tankersley wonders about why the stock market loves Donald Trump. He notes how the rally started off powered by banking stocks, which made sense in light of promises of deregulation. Goldman Sachs alone accounts for over 20% of the gains in the Dow Jones since the election. However, the rally has then progressively spread across industries (see figure below for the sector performance numbers for the S&P 500). By now, it is fuelled by a generalised spike in business confidence. This also comes on the back of very strong labour market figures bequeathed to the new POTUS by the Obama administration.

Source: BloombergView

Testifying before the House of Representatives Committee on Financial Services, the Federal Reserve Chair Janet Yellen explained how, in her view, the current stock market run is led by the fact that market participants are likely anticipating shifts in fiscal policy that will stimulate growth and possibly raise earnings. She noted how this is accompanied by a rise in long-term interest rates and strengthening of the US dollar.

In a note to investors, Erik Nielsen of Unicredit points out that the current stock market rally is mostly fuelled by the conviction that Trump will implement only the “good” part of his campaign promises (tax cuts, deregulation, infrastructure building), while refraining from pursuing the “bad” promises (trade wars, import tariffs, unravelling multilateral agreements). To him, this conviction is largely ungrounded.

Larry Summers is persuaded that markets are on an unmotivated sugar-high that will not last a year. He makes the point that it is a mistake to judge policy on immediate market reactions rather than changes in the fundamentals. In the end, the past president who enjoyed the best post-election pre-inauguration stock market performance was Herbert Hoover, just ahead of the 1929 Great Depression. In line with Kenneth Rogoff, he points out that authoritarian governments have historically brought bull markets, before leading countries to disaster.

According to Robert Schiller, the US is living through two simultaneous illusions: that Trump is a business genius and that stock markets are hitting never-ending new records. These claims, and the link between the two, are only in the President’s interest. Two days after Trump’s election, the Dow Jones hit a new record high – and has since set 16 more daily records, all heralded by the media. However, the Dow had already hit nine record highs before the election, when Hillary Clinton was projected to win. Moreover, if you look at it in real terms, the Dow is up only 19% since 2000, which is rather underwhelming in a 2% inflation target environment.

Paul Krugman concedes that, contrary to his early predictions of a financial market crash in the case of a Trump election, stock prices have indeed grown. However, the fluctuation is not that big by historical standards. Looking at the change in government bond yields, he argues that the market must be pricing in a stimulus package of roughly 1% of GDP. He therefore concludes that the hype about a “Trump effect” is much overdone.

Nouriel Roubini enriches this analysis by detailing how the fiscal stimulus envisaged by the President will benefit disproportionately large corporations, based on steep cuts in corporate and capital gains taxes. It is therefore natural that stock markets are heading north. However, he expects this financial honeymoon to end soon. In a close to full employment environment, a fiscal stimulus could fuel an already rising inflation to the point that the Fed would be forced to hike up interest rates faster than originally expected. This would compound the dollar appreciation that has already been observed since the President’s election.

Ultimately, as Larry Summers remarks, nearly half of the S&P 500 revenues are earned abroad, and these will be harmed by a strengthening of the currency and Trump’s protectionist agenda, which might easily turn into a trade war. He concludes that promises of lower taxes and deregulation can only boost financial markets in the short term.

A dissenting opinion comes from Kenneth Rogoff, who underlines how Trump’s unorthodox policies might easily push the US economy above a 4% growth clip in the short run. Ultimately, aside from his protectionist views, he is extremely pro-business. Moreover, the impact of a demand boost on inflation will depend crucially on whether productivity in the US has flattened for structural reasons, or because there are underutilised and unemployed resources. If the low business investment is at the origin of it, Trump’s policies might have a considerable effect on the economy in the short run. As such, he invites to beware of pundits who are certain of an upcoming economic catastrophe. At least for a while.

The New Yorker synthesises this review on a facetious note.