Chinese banks: An endless cat and mouse game benefitting large players

As deleveraging moves up in the scale of objectives of the Chinese leadership, banks now face more restrictions from regulators. As a result, banks ha

This piece was originally published in Asian Banking & Finance.

Ever-changing sources of funding in regulatory whirlpool

When one door closes, another one opens up. As deleveraging moves up in the scale of objectives of the Chinese leadership, banks now face more restrictions from regulators. In any event, this is not the first time they find themselves in the regulatory whirlpool. From the usage of repo agreements to wealth management products (WMPs), and most recently negotiable certificate of deposits (NCDs), banks have been very creative in playing the cat and mouse game in front of evolving regulations.

Flourishing financial innovation has helped China’s leverage process to continue unabated. However, with the tightened stance of open market operations by the People's Bank of China (PBoC), liquidity seems to be increasingly scarce, pushing up the cost of funding. In fact, SHIBOR is already at record high since the difficult events in 2015, hovering very close to 3%.

Regulatory pressure evolving much faster than before

China's central bank has introduced Macro Prudential Assessment (MPA) to contain financial risks in the economy, which serves as a quarterly report card for banks. Various indicators are included in the assessment framework from the beginning, such as loan growth and asset quality condition. Banks with poor score will be punished with a higher cost of funding.

This is later further expanded to cover off-balance sheet WMPs, which has been a very common way among small and medium size banks to increase financial leverage and save the declining profitability due to lower net interest margin. Since the inclusion of WMPs into the MPA, the outstanding amount has already shrunk by 1.6 RMB trillion to 28.4 RMB trillion in May 2017.

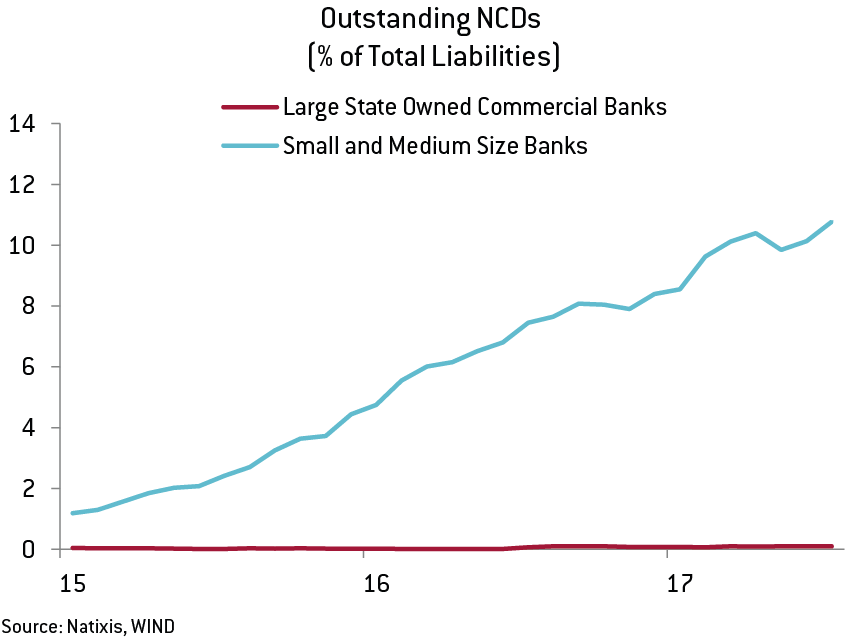

After the People’s Bank of China limited the use of WMPs, the latest move targeted at the issuance of NCDs, which are short-term, non-collateralized paper with an even higher funding cost than the SHIBOR. This has led to a fall in issuance, but has grown again since June 2017. The underlying reasons could probably be a lack of other options and the regulations are not as tight as they may appear on the surface.

The most important point is that the PBoC’s pressure affects banks very differently: it penalizes banks short of liquidity and benefits those long of liquidity. This simply means that China’s five largest commercial banks (all state-owned) are the winners (with an implicit government guarantee which allows them to benefit from flight to quality) while the others are the losers.

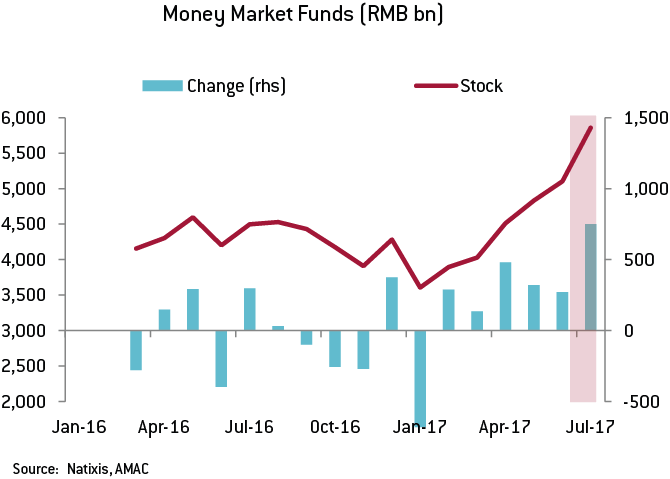

Money market funds are the new intermediaries

As liquidity is increasingly expensive, liquidity scarce banks have recently renewed their strategies to access funding in a different way, namely through money market funds (MMFs). While banks are pressured to hold less interbank assets, money market funds (MMFs) are relatively more flexible. MMFs act as intermediaries to hold NCDs, and hence repackage products for retail and institutional investors. In fact, MMFs have seen a massive increase in July 2017, rising 15% to 5.86 RMB trillion in a single month. As a relative measure, the size of MMFs has grown from 6.4% of the interbank market in January 2017 to 9.5% in July 2017. And 19% of the MMF is invested in NCDs as of Q2 2017.

The quick pace of expansion may pose extra liquidity risks especially when three-quarter of the assets have a maturity less than 90 days. This kind of regulatory arbitrage will expand until the loophole is close as has happened with WMPs or NCDs in the past. It goes without saying that this only adds additional financial leverage to China’s already highly leveraged financial sector.

Financial innovation a the cost of an increasingly due banking sector

The flurry of new funding instruments for Chinese banks is another sign of China’s financial innovation. While positive in a vacuum, the reality is that the risks associated with such innovation do need to be assesses carefully. Chinese regulators are obviously aware, which explains their zeal to introduce new sources of financing in the PBoC’s MPA. However, that is only pushing banks new – and increasingly less safe – sources of funding.

In addition, given the large share of state-owned ownership in Chinese banking sector with a much larger deposit base, the search for funding is only affecting one part of the banking sector. In other words, while small banks are struggling for liquidity, large banks stand to benefit from the regulatory crackdown. The latest 2017 Q2 results have confirmed our expectations that large banks can gain from regulatory arbitrage and risks are rising for smaller banks. In other words, the improvement in bank results is not only due to better economic conditions but also to regulatory arbitrage. State-owned commercial banks (SOCBs) have seen improved net interest margin but generally not for smaller banks. This is mainly due to a continuous increase in funding in the shadow banking, which smaller banks heavily depend on. In other words, the improvement in bank results is not only due to better economic conditions but also to regulatory arbitrage.