The Turkish Crisis

Financial markets have been very nervous about Turkey for the past few weeks. We review economists’ opinions about the economic, political and geopoli

Jamie Powell and Colby Smith write on FT Alphaville that the Turkey crisis looks like a classic emerging-market meltdown: a rapidly growing economy funded by short-term, dollar-denominated liabilities, fronted by a strongman leader with a penchant for appointing insiders to key government positions. As such, it is evocative of the Asian currency crises of 1997 and 1998, which hold lessons for Turkey.

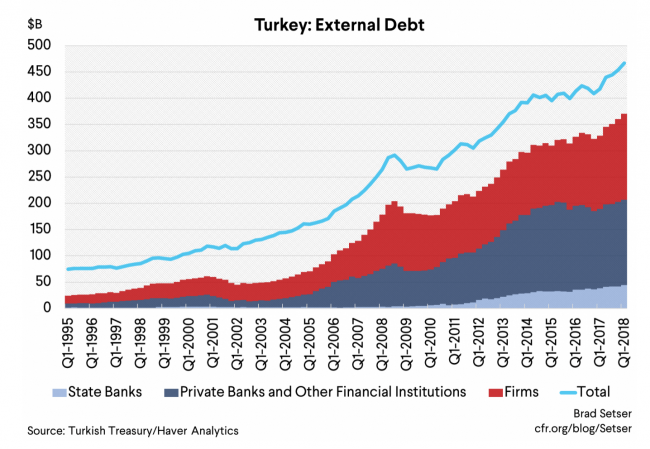

Brad Setser thinks instead that while Turkey has some similarities with the Asian crisis countries of the 1990s, it also has important differences. Turkey’s banks are the main reason why the currency crisis could morph into a funding crisis, one that leaves Turkey without sufficient reserves to avoid a major default. But, unlike Asian banks, Turkey has been able to use external foreign currency funding to support a domestic boom in lira-lending to households. Turkey’s banks really didn’t need to borrow foreign currency from the rest of the world to support their current level of foreign currency lending to Turkey’s firms, and their apparent wholesale funding need is for lira, not dollars. Also the real boom in credit has come not from foreign currency lending to firms, but rather from lira-lending to households. The financial mystery – which Setser then goes on to explain – is not how the banks lent foreign currency to domestic firms, but how they used external foreign currency borrowing to support domestic lira-lending.

Jacob Funk Kirkegaard writes that economic developments are driving Turkey to all but inevitably approach the IMF for its second bailout in the 21st century. Turkey’s basic difficulties derive from the twin deficits it has been running in recent years. Making Turkey’s problems worse are a range of political difficulties relating to its relationship with NATO, the European Union, and the United States, as the country is more isolated internationally than at any moment in recent decades.

The road thus points to the the IMF, but the Fund will find it difficult to help Turkey without demanding tough austerity policies in return – policies that could weaken Erdoğan’s hold on power. Erdoğan does have some potential (if unsavory) political leverage, however, as a seemingly imminent Syrian government attack just south of the Turkish border could easily unleash another refugee emergency inside Northern Syria. Turkey’s decision whether or not to open its borders and provide refuge for Syrians could well be political in nature, possibly contingent on economic aid from the West or the terms of an IMF rescue package.

Grégory Claeys and Guntram Wolff disagree and argue that a correction in Turkey’s macroeconomic policies is needed, but it is too early to say that Turkey will need a bailout programme. European policymakers should, however, reflect on what should be the EU’s position towards Turkey. A financial crisis in a neighbour country of the EU could have a direct negative impact on the EU economy, mainly through the exposure of its banks operating in Turkey and through trade.

Moreover, a crisis in Turkey could trigger possible political knock-on effects and consequent changes in Turkey’s migration policy, not to mention geopolitical threats. If an IMF programme were to be unfeasible, and EU countries were to come to the conclusion that avoiding an escalation of the crisis in Turkey is in their best interest, the EU could try to organise a financial support package on its own through its Macro-Financial Assistance (MFA) programme, reserved for non-EU partner countries. But in that case, the EU needs to form a clear view on whether such an instrument should be a way to advance democratic values, or whether the EU should have a more functional approach and limit conditionality on specific macro-structural policies.

Laurence Daziano writes that this is a chance to reset Europe’s relationship with Turkey. This should be achieved by means of an EU-Turkey treaty that would have three components. On the diplomatic and security side, the reaffirmation of Turkey’s anchoring in the western camp and Nato; on the economic side, a substantial increase in European aid and a guarantee of the independence of the Turkish central bank, and a commitment to curb inflation; and, finally, the further transposition of European standards into Turkish law. This project does not require the sensitive question of the future of EU accession talks between Brussels and Ankara to be settled. On the contrary, this is a propitious moment to propose a resetting of relations between Europe and Turkey, since Mr Erdoğan is looking for allies. At a time when Mr Trump treats Europe as a “foe” of the US, the bloc would do well to help Turkey to modernise further and to encourage the liberal and democratic values to which many Turks still subscribe, especially young people and those living in the country’s large cities.

Jim O’Neill writes that Turkey must now drastically tighten its domestic monetary policy, curtail foreign borrowing, and prepare for the likelihood of a full-blown economic recession, during which time domestic saving will slowly have to be rebuilt. Among the regional powers, Russia is sometimes mentioned as a potential saviour. While there is no doubt that Vladimir Putin would love to use Turkey’s crisis to pull it even further away from its NATO allies, Erdoğan and his advisers would be deeply mistaken to think that Russia can fill Turkey’s financial void: a Kremlin intervention would do little for Turkey, and exacerbate Russia’s own economic challenges.

Qatar, one of Turkey’s closest Gulf allies, could provide financial aid but does not have the wherewithal to pull Turkey out of its crisis single-handedly. As for China, though it will not want to waste the opportunity to increase its influence vis-à-vis Turkey, it is not the country’s style to step into such a volatile situation, much less assume responsibility for solving the problem. That means that Turkey’s economic salvation lies with its conventional Western allies, and despite his escalating rhetoric Erdoğan may soon find that he has little choice but to abandon his isolationist and antagonistic policies of the last few years.

José Antonio Ocampo argues instead that longstanding patterns in emerging markets may no longer apply. At the peak of the Turkish turmoil, in the week between August 8th and 15th, the currencies of Argentina, South Africa, and Turkey depreciated by between 8-14% against the US dollar. Yet the currencies of other emerging economies depreciated by no more than 4%.This suggests that contagion is not taking hold as easily as it has in the past, and that broad-based sudden stops may be less likely.

Even the most affected economies were able to limit the fallout of their currency collapses. This seems to reflect a new resilience to contagion that has formed over the last ten years or so. But that does not mean that emerging economies are in the clear; on the contrary, they still have plenty to worry about, not least an escalating trade war. Smart policies, together with an improved global financial safety net from the International Monetary Fund, therefore remain of the utmost importance

Alasdair Mcleod at Mises Institute is interested in long-term implications for the US dollar. He argues that President Trump’s actions over trade, which appear to have some short-term successes, are driving countries away and ultimately this will prove counterproductive. Speculators buying into Trump’s short-termism and the Fed’s normalisation policies are for the moment driving the dollar higher, without realising that foreigners, far from suffering from a shortage of dollars, already own all the excess dollar liquidity created since the Lehman crisis. The dollar is rising only on short-term considerations, but once these abate, the longer-term prospects for the dollar will reassert themselves, including the escalating budget and trade deficits, record levels of foreign ownership of the dollar, and rising prices fuelled by a combination of earlier monetary expansion and the extra taxes of trade tariffs.