Hong Kong’s economy is still important to the Mainland, at least financially

Hong Kong’s current situation is important for the world in as far as its role as major offshore financial centre is key for China’s inbound and outbo

Discontent is running deep in Hong Kong, currently facing the most severe political crisis since the handover almost two decades ago. The recent turmoil has prompted analysts to review Hong Kong’s economic importance to Mainland China and many have concluded that what was the once “Pearl of the Orient” is no longer important. It is true that the share of Hong Kong’s GDP to the rest of China has declined from 16% in 1997 to 3% in 2018 (Figure 1). Statistics seem to provide a clear view of Hong Kong waning relevance but this is not the full story. A narrow comparison solely focusing on the evolution of GDP masks Hong Kong’s economic and financial relevance, not only to Mainland China, but also to the rest of the world.

Figure 1: GDP of Hong Kong and Mainland China

Source: Natixis, Bloomberg

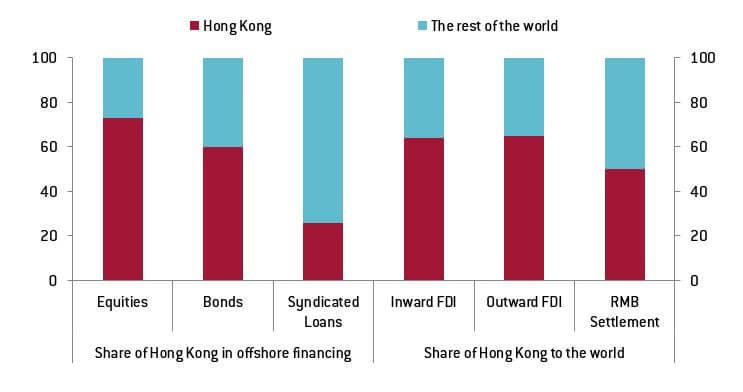

To gauge Hong Kong’s real relevance, we need to move beyond GDP and consider the key soft spot for Mainland China. This is Hong Kong’s financial acumen and, in particular, its offshore centre status. To build an offshore centre of the size of Hong Kong, with global relevance, the city’s economic foundations are based on free capital movement while Mainland China still maintains a relatively closed capital account. This means that Hong Kong can facilitate the Mainland’s access to foreign capital. In fact, Hong Kong is Mainland China’s preferred offshore centre. As regards raising funds offshore, Hong Kong was the home of 73% of Mainland companies’ initial public offerings (IPO) overseas during the period 2010 to 2018. In the same vein, Hong Kong accounts for 60% of overseas bond issuance of Mainland companies and 26% of their syndicated loans (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Hong Kong's Financial Relevance to Mainland China (2010-2018)

N.B. Non-listed bonds are excluded from calculation. OFDI data as of 2010-2017. RMB settlement data as of 2018.

Source: Natixis, Bloomberg, The People's Bank of China, China Ministry of Commerce

Beyond funding, Hong Kong is China’s most important springboard for foreign direct investment, either into or outside China. In particular, 64% of Mainland China’s inward FDI comes from Hong Kong and between 2010 and 2018, 65% of outward FDI was channelled through Hong Kong. The high share indicated Hong Kong’s role as the immediator between China and the West, which is due to the trust of Chinese and foreign firms on Hong Kong’s institutional framework and funding pool for their investments. In the specific case of mergers and acquisitions, Hong Kong has played a key role as its unique status has facilitated Chinese companies' overseas acquisitions.

In addition, Hong Kong has long been China’s largest offshore RMB centre, for long a key policy initiative of the Chinese government in its pursuit of a staggered opening of the capital account. Other than RMB settlements, Hong Kong also holds a special access to China’s equity and fixed income markets, though the Stock and Bond Connect.

Therefore, Hong Kong’s role as the China’s financial arm for the rest of the world has helped Mainland China in keeping its financial sector insulated without suffering the negative consequences of such isolation, i.e. limited access to finance or difficult access to assets in the rest of the world. In essence, Hong Kong has long been China’s financial firewall.

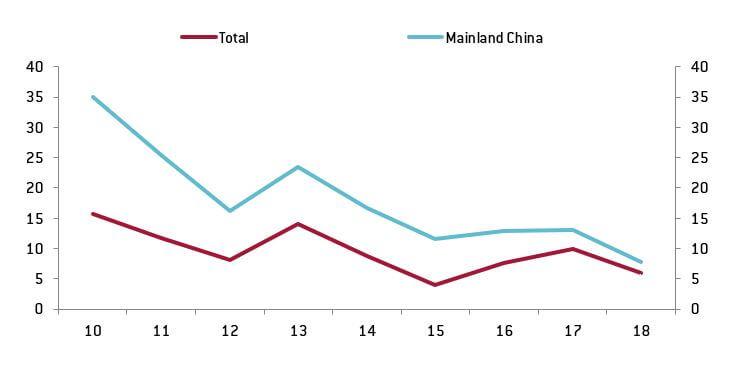

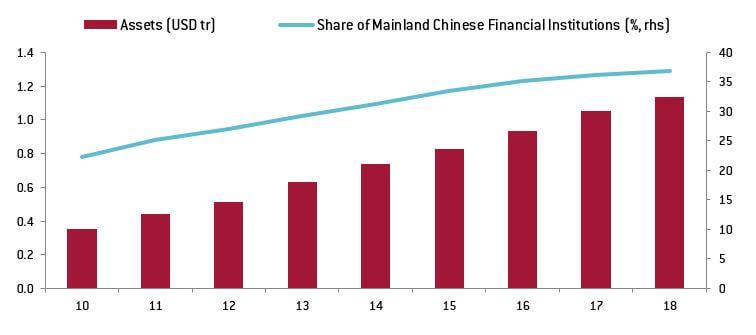

The second important aspect to consider is that Hong Kong’s financial system is increasingly dominated by Mainland Chinese banks. At the same time, overseas bank assets held by Mainland Chinese banks are also heavily concentrated in Hong Kong. The large exposure means that the destiny of Hong Kong as an offshore financial centre affects China even more than it affects those from the rest of the world. Mainland Chinese financial institutions have expanded 3.2 times since 2010, reaching USD 1.2 trillion (Figure 4) and have had a much higher growth rate than the rest of the banking sector (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Growth Rate of Bank Assets in Hong Kong by Institution (%YoY)

Source: Natixis, Hong Kong Monetary Authority

Figure 4: Assets of of Mainland Chinese Financial Institutions in Hong Kong

Source: Natixis, Hong Kong Monetary Authority

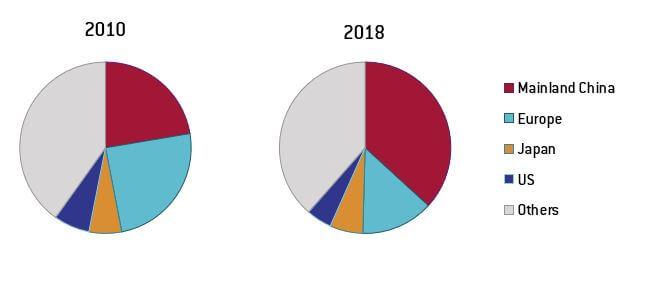

While Hong Kong’s bank assets have grown very fast in an aggregate term, China has outpaced all the other countries as their share of assets in Hong Kong’s banking sector increased from 22% in 2010 to 37% in 2018 (Figure 4). The surge draws deep contrast to European banks, which have barely increased its exposure in Hong Kong, and the much slower pace of Japanese and American players (Figure 5).

Figure 5: Total Bank Assets by Region/Economy of Beneficial Ownership in Hong Kong

Source: Natixis, Hong Kong Monetary Authority

Finally, Hong Kong’s offshore financial sector has been extremely successful so far, at least when measured by the increase in size. Bank assets-to-GDP ratio has expanded from 462% in 2002 to 846% in 2018. Since the introduction of the currency board in 1983, Hong Kong managed to keep the currency peg and stability amid political risks from time to time.

The dilemma that Hong Kong is facing is the increasing dependence on Mainland China both economically and financially has happened with the HKD pegged to the USD under a strict currency board arrangement. In other words, while shocks to the economy are likely to come from Mainland China, Hong Kong cannot count on any exchange rate or monetary policy due to its dependence and linkages to the FED.

There is no doubt that the current HKD regime has helped Hong Kong build a massive offshore financial centre, but it does not offer any respite if a negative shock affects the economy, which is exactly where we are today. And the same huge size of China’s offshore centre can become a problem if Hong Kong experiences capital outflows as a consequence of recent events. In other words, while Hong Kong forex reserves can cover the monetary base by approximately 2 times, the lack of capital controls implies that capital flows can be very volatile. If we add the fact that deposits in Hong Kong are massive, which amounted to USD 1.7 trillion and equivalent to 469 % of GDP, it seems obvious that forex reserves are not as ample if they need to continue to cover the monetary base in a situation of large deposit withdrawals.

Not only is Hong Kong important to the rest of China, especially in the financial sector, but its intrinsic risk is also even higher than that of other financial centres as it sits on a very rigid monetary regime. Beyond Hong Kong’s financial institutions, those who will be the most affected by the arising risks are clearly the Mainland Chinese banks in town.