EU support for SME IPOs should be part of a broader package that unlocks equity finance

The incoming Commission President has put support for SMEs at the centre of her economic programme. A public-private fund investing in initial public

Over the first five years of the EU’s capital markets union (CMU) agenda the financing mix of European small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) has barely changed, and remains heavily biased towards internal funds, and bank loans. Figures from the latest EIB investment survey show that for medium sized companies external finance accounted for about 37 per cent of investment finance, and that within that component loans and other types of bank finance accounted for about 60 per cent. Newly issued bonds and equity, by contrast, amounted to less than one per cent in total.

The CMU agenda to date has already focused on the various obstacles that SMEs encounter in raising finance on public markets:

First, investors typically find it difficult to evaluate small firms with short track record. Bridging information gaps may have become more daunting for SMEs since brokers had to ‘unbundle’ investment research from execution services under MiFID II since 2018.

Secondly, costs of going public can be substantial. The initial listing will entail underwriting fees, costs for legal advisers, accountants and auditors, and fees payable to the exchange. These costs have a substantial fixed component, so are more prohibitive for smaller companies (according to a recent study this could be 5 to 8 per cent of the amount raised where issuance volume is between EUR 50 to 100 million). Since 2017 there is a streamlined requirement for the prospectus offered by SMEs in an IPO, though ongoing disclosure and compliance costs for listed companies remain daunting for SMEs.

Thirdly, the inherent illiquidity in public equity of smaller firms will raise the cost of capital. With the concept of the so-called ‘SME growth markets’, MiFID II put in place a market type that benefits from various types of lighter regulation, for instance under the prospectus regulation, and the market abuse (insider) regulation. A legislative package under the CMU agenda that was agreed last March now seeks to facilitate trading and raise liquidity further.

Europe’s SME exchanges

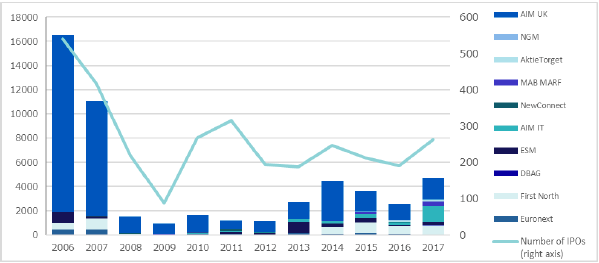

Despite past reforms, SMEs remain largely uninterested in external equity. In the EIB survey the proportion of firms that signal interest in new bond or equity issuance are vanishingly small. Issuance on the EU’s junior exchanges that are dedicated to SMEs, such as the New Connect market in Warsaw, has remained well below pre-crisis peaks. The chart below shows roughly EUR 4.5 billion issuance in about 250 IPOs in 2017. Many of these exchanges remain illiquid, and AIM at the London Stock Exchange still accounts for the bulk of European SME IPOs.

Number of IPOs and funds raised (EUR million) on EU junior exchanges:

Source: European Commission.

It is the avowed aim of the Commission’s CMU agenda to mobilise risk-oriented funding for growth companies. With this broad objective there should be no bias towards public markets, as opposed to private equity and venture capital.

In terms of volumes of finance, it is clear that private equity funding outstripped what has been raised through SME IPOs on the Europe’s junior exchanges. Last year, the European private equity sector raised about €97 billion in funds, and invested €80 billion. Nearly half of buyout investment was done in small or mid-market deals of under €150 million each (where there were over 1,200 investments). Compared to IPOs, a larger number and a more diverse set of SMEs have benefited. Arguably, an expansion of private equity finance could be supportive of public markets. These investors typically foster governance and operational changes that make a company more attractive for a subsequent listing, though this is of course often resisted by established owners.

Governance of additional EU support

A new EU fund dedicated to SME IPOs, as it is now proposed, would make the success of a stock exchange debut more likely, and possibly redress the illiquidity problem that may have discouraged preparation of an IPO in the first place. But such a fund should be solely targeted at a well-defined failure in financial markets. This affects primarily small young firms with risky projects.

A new EU programme should crowd in private capital, rather than displace it. This could for instance be done through quality certification of potential issuers, based on the existing national and EU programmes of pre-IPO support, and this should evenly open up all of Europe’s SME growth markets (without bias to the local exchange). A EU IPO fund should not support markets that are inherently illiquid, when in fact issuers would have been better served by a cross-border listing elsewhere in Europe. The Zagreb stock exchange, for instance, now runs a SME trading platform jointly with Slovenia.

Direct investment of EU (or EIB) funds in highly risky young firms would throw up numerous governance problems. Venture capital of course stands out for extensive and costly screening processes, which require specialist skills. Firms that were listed on Europe’s junior exchanges have shown mixed performance at best, and were often beset by corporate governance problems. Support to ‘funds of funds’, as increasingly used by the European Investment Fund, could remove direct control, though this model is costly and would need to be carefully evaluated.

A fresh look at the CMU agenda

The policy direction set out in the Commission President’s manifesto is sensible, as it promises a fresh look at the CMU agenda with a focus on the innovative and strongly growing mid-sized companies. This will entail difficult trade-offs between the aim of greater market funding and liquidity on the one hand and the principles of market integrity, transparency and stability in some of the recent legislation such as MiFID II on the other. A new EU fund could overcome some market failures, and may fit well with the EIB’s increasing focus on equity finance, where some public-private funds have had a successful launch. At the same time, SMEs will need to gear up to a life as a public company, including for the changes new owners can bring, and private equity funding and the broader ‘eco-system’ of capital market services will need to be built.