Non-performing loans’ legacy versus secondary markets

Eleven years since the start of Europe’s financial crisis, and the legacy of non-performing loans in the EU, though much smaller, is still a live issu

No doubt success has been achieved as the asset quality of banks in the EU area has improved reaching 3% as of June 2019 (EBA Risk Dashboard – Q2 2019), compared with its peak of approximately 7.5% in 2012 (EBF). The total stock of NPLs held by the banks reduced to EUR 636bn as of June 2019 (EBA Risk Dashboard – Q2 2019). This success has been mainly down to three developments:

- Progress, as marked in Fourth Progress Report on the reduction of NPLs and further risk reduction in the Banking Union, on the Council of the EU’s action plan including focus of the European Commission, European Central Bank, European Systemic Risk Board and European Banking Authority on the reduction of non-performing loans.

- Banks’ efforts in workout combined with development of special asset management companies and the secondary markets in some member states.

- And rather good economic climate over the last few years: positive economic growth, lowering unemployment, low-interest rates and a favourable situation in real estate.

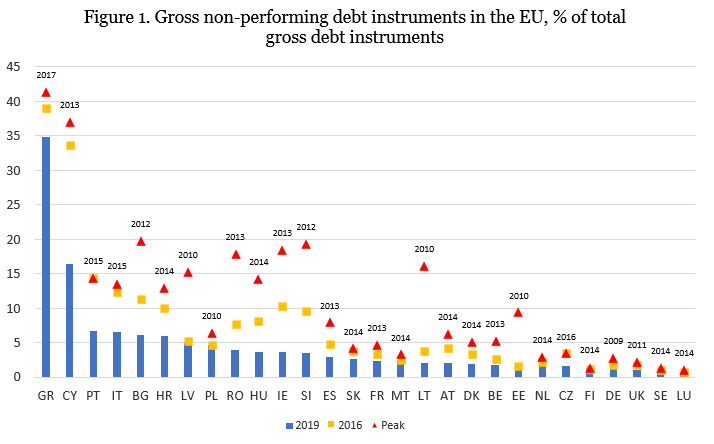

However, the generally positive picture is somewhat twisted when it comes to individual member states. On the one hand, in terms of the NPL ratio (Figure 1.) Luxembourg, Sweden, the UK, Germany and Finland are doing well. On the other hand, Greece and Cyprus are recording two-digit numbers, followed by Portugal, Italy, Bulgaria and Croatia with the NPL ratios from 6.6% to 5.9% respectively.

Stock-wise relative to GDP (Figure 2.), still in 2019 Greece and Cyprus take the lead, however, together with Portugal, Italy, Spain and Ireland they have made progress in reducing NPL volumes since December 2016.

As historical cases of effective NPL reductions (e.g. Ireland, Spain, Italy, UK, Germany, Slovenia) have been somehow linked to the secondary markets. Let's contrast the NPL results with developments on the European loan portfolio market. In Deloitte’s report Deleveraging Europe the volume of European loan portfolios traded effectively doubled in just two years, reaching over €200bn in 2018, compared with €109bn in 2016 (Figure 3). The numbers for 2019, including ongoing transactions, will not repeat the last year’s volume but still look promising.

In terms of volumes and the number of deals (Figure 4.) Italy, Spain, UK, Ireland, Germany, Greece, Portugal and Cyprus account for most transactions. This proves that sales in the secondary markets, specifically for countries with high stocks of NPLs is an effective way of reducing NPLs. Moreover, such an outcome has also been reflected in analysts’ responses under the 2019 autumn EBA’s RAQ, where they ranked the investors’ appetite for NPLs as the main driver of the reduction in NPL levels during the past few years, followed by the development of secondary markets for NPLs and an accommodative macroenvironment. Additionally, nearly all countries active on the European loan market have resorted at some point to either establish an asset management company (AMC) (e.g. Italy (AMCO, former SGA), Spain (SAREB), UK (UKAR), Ireland (NAMA), Germany (FMS-W, EAA), Portugal (Banco Espirito Santo) or introduce public guarantee schemes (GACS in Italy).

In general, AMCs or so-called “bad banks” have been set up to help the banks clean up their balance sheets. They could be developed in two ways, either as a centralised AMC or as a “bad bank” separated from the remaining good portfolio of a troubled bank. The report by the Financial Services Committee states that state aid-supported AMCs, usually of a larger magnitude, can help kick-start secondary markets for NPLs. Also, the EBA report on NPLs supports this view. However, solutions involving the state aid component must be notified to and approved by the Commission. Such an approval follows lengthy valuations and is subject to strict conditions, one of them consisting in capping the transfer price which basically cannot be higher than the long-term real economic value of the assets.

Having in mind the complexity of EU regulatory framework, as a part of the action plan the Commission in March 2018 published the AMC Blueprint to provide practical guidance for the design and set-up of national impaired asset measures. According to it, AMCs can be private or (partly) publicly backed. If the country acts as a standard economic agent, AMCs are not considered as state aid. However, the design of an AMC with a state aid component represents an exceptional solution subject to such EU regulations as the Bank Recovery and Resolution Directive, the Single Resolution Mechanism Regulation and state aid rules. In practice, it translates into tighter rules for transfer pricing of assets, for example a need to price them at their estimated market value which often would mean significant and immediate losses for banks. In the case of state guarantees the same logic can be observed. It translates into whether a normal market economy operator would provide a guarantee to the bank under the same terms as a state.

The exceptionality of state-supported solutions has been well reflected in the debate on holding banks accountable for their decisions. It should not be easy to make the taxpayer foot the bill for the past lending decisions. It might generate moral hazard which in turn may cause further market disruptions.

Despite of all restrictions, as stated in the paper by Christophe Galand, Wouter Dutillieux, and Emese Vallyon, impaired asset relief measures, oſten combined with private or state recapitalisations, are a possible tool to remove (or reduce) the risk and uncertainty from a bank’s balance sheet. Moreover, Alexander Lehmann in his paper points that only a complete separation of the affected assets into a legally distinct balance sheet would meet the dual objectives of further drain of questionable assets on the capital and profitability of core assets.

Taking this into account, regardless of the state aid issue which itself might constitute an obstacle to the setting-up of an effective AMC, AMCs seem to be a good solution for releasing frozen bank capital, recovering the lending and, hence, making the banks profitable again. This all makes the case for further development of well-operating secondary markets for NPLs.

In view of the above, let’s have a closer look at Cyprus and Greece – two countries still reporting the highest NPL ratios. Do they have any systemic solutions in the pipeline?

The Cypriot three pillar NPL reduction strategy covers two special solutions. These are: (1) the establishment of the state-owned AMC KEDIPES and (2) the set-up of the state-support ESTIA scheme. Unfortunately, the progress on the strategy have been slow. The KEDIPES’ organisational set-up and work-out strategy have been still in the making. For those with more than a half-year delay an adviser – the consultancy BDO Ireland (having expertise in Irish NAMA) has been selected. With its help KEDIPES will also assess whether to continue cooperation with Altamira, its current debt servicer. The ESTIA scheme has also been launched with a delay and it has been delivering far below the expectations. According to the data quoted by online news site Stockwatch, only around 350 borrowers, out of the estimated 12 000 eligible have applied. These 350 applications correspond to around €110m of NPLs in comparison to the estimated more than EUR 3bn NPLs to be covered by the scheme. In the analysts’ opinion favourable legislation in place to protect a borrower’s primary home and the pressure to weaken the criteria make integration into ESTIA scheme unnecessary (Financial Mirror – Cyprus). Against this background in 2018 Cyprus has managed to reduce its stock of NPLs (from EUR 20.6bn at the beginning of 2018 to €10.2bn at the end of 2018). This has been mainly driven by two one-off transactions, i.e. the transfer of the non-performing Cyprus Cooperative Bank assets, amounting to nearly €5.7bn) (the remaining good portfolio sold to Hellenic Bank) to KEDIPES and the sale of an NPL portfolio of €2.7bn by Bank of Cyprus to funds affiliated with Apollo Global Management. Going forward, completing KEDIPES is of great importance as well as proper implementation (maybe fine-tuning) and better utilisation of the ESTIA scheme.

Greek NPL market nearly did not exist in 2016, but equipped with measures under the ESM programme (e.g. a simplified framework for licensing of credit servicing firms, enhanced rights for secured creditors in the distribution of NPL liquidations during 2018, launch of e-auction platforms) it grew to the third-largest in Europe with over €16bn traded in 2018 (Deloitte’s report Deleveraging Europe). Greek banks in 2018 managed to sell €11bn of NPLs, mainly through securitisation (EBA report on NPLs). In addition to revival of secondary markets, in October 2019 the Commission approved a Greek asset protection scheme, stating that state guarantees are to be remunerated at market terms according to the risk taken. The scheme, called HERCULES, is comparable to the Italian GACS scheme and provides as much as €9bn in state guarantees on NPL securitisations. HERCULES will involve setting up special purpose vehicles (SPVs) that will purchase the non-performing loans from the banks. That sale would be financed by notes issued by the SPV with a government guarantee for senior tranches. Moreover, the Commission consented as well to the Greek Primary Residence Protection Scheme with an annual budget of €132m and strict eligibility criteria in terms of a property value and borrower’s income. Borrowers can receive a grant corresponding to 20–50% of their monthly loan repayment.

Both, Cypriot and Greek, developments could succeed in shifting large stocks of NPLs into legally separate entities, thereby freeing banks’ capital and returning capacity to focus on core business as well as engage in new lending. Both are designed to navigate well the EU’s restrictions on state aid which could be an issue if loans are transferred at higher prices than (often very low) market ones. They could also benefit from the economies of scale resulting from the centralisation of assets and collateral as well as concentration of human resources with appropriate expertise. Finally, they could stimulate investor interest in rather non-transparent assets.

Last but not least, the EU regulatory context is going to play an important role in the further development of the secondary markets. Here finalising a proposal for a Directive on credit servicers, credit purchasers and the recovery of collateral is essential. This piece of legislation is supposed to act in two ways. First, its aim is to facilitate the process of outsourcing of the servicing of NPLs by banks to a specialised credit servicer or the sale of the credit agreements to a credit purchaser with the appropriate risk appetite and expertise to manage it. Secondly, it is supposed to improve the recovery of NPLs through so-called accelerated extrajudicial collateral enforcement. The two components reinforce each other as shorter time of resolution and increased recovery increases the value of NPLs and bid prices in NPL sale transactions. As stressed in the paper by Peter Grasmann, Markus Aspegren and Nicolas Willems the proposed Directive would contribute to the further development of secondary markets for NPLs. So far there is, unfortunately, no agreement in the Council as to the recovery of collateral part. Only the position on secondary market part of the Directive has been adopted.

To further stimulate NPLs secondary markets, following the action plan, the European Banking Authority, the European Central Bank and the Commission have been working on NPLs transaction platforms. In November 2018 a staff working document on the potential set-up of an NPL transaction platform was published. Such a platform could act as a channel for the efficient disposal of both current and future NPLs and hence constitute a part of sustainable solution to the NPL issue in the EU. Already two meetings of the roundtable with industry stakeholders took place giving input for further works of the Commission in cooperation with the European Central Bank and the European Banking Authority.

As the NPLs’ ratios have been reduced across the EU with only Greece and Cyprus still struggling with higher numbers, it might be reasonable to come back to the idea of having a pan-European AMC, however, in the different context. This time, not as an effective ex-post special asset relief measure but as a standard solution operating under the sound resolution planning and as an integrated part of a reliable recovery strategy for the banking sector. Set-up of the pan-European AMC could send a strong signal to investors that Europe wants to systemically deal with NPLs that naturally appear in the banks’ balance sheets and would contribute to the further development of the European secondary market for NPLs. However, taking into account countries’ disputes on the out-of-court collateral recovery, it seems to be a big challenge, at least, for now.

To conclude, the further development of secondary markets as well as the application of dedicated solutions like AMCs, asset protection schemes or transaction platforms both at the national and at the EU level seems to be vital in effective NPL problem resolution. Nevertheless, to make the secondary markets do their job, a good and timely progress on making the foreclosure, restructuring, insolvency and judicial systems work smoothly is rudimentary. No longer should the capacity of the active European loan portfolio market be underestimated for the purpose of deleveraging Europe.

The author is a senior specialist at Narodowy Bank Polski visiting Bruegel.

The views expressed in this blog post are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official position of Narodowy Bank Polski.