Does the Eurogroup's reform of the ESM toolkit represent real progress?

The deal reached on euro-zone reform at the December 4th Eurogroup is not ground-breaking. However, it contains a number of incremental but potentiall

At the December 2018 Eurogroup meeting, finance ministers from the euro area did not manage to agree on a euro-area budget with a stabilisation function, nor make progress on a timeline to establish a European Deposit Insurance Scheme (EDIS) in the future. However, they agreed on a series of incremental – but potentially key – technical reforms in order to strengthen the euro architecture: a European Stability Mechanism (ESM) backstop for the Single Resolution Fund (SRF), a reform of the ESM toolkit, and the inclusion of single-limb Collective Action Clauses (CACs) in euro-area sovereign bonds. In this blog post, we focus on the last two points (for a view on the SRF backstop, see my Bruegel colleagues’ blog post on this question).

As argued in a previous blog post, we believe that the ESM is the cornerstone of the current euro-area architecture. In particular, given that the Outright Monetary Transactions (OMT) programme of the ECB is conditional on the participation in an ESM programme, the ESM would have to play a fundamental role if a country is affected by a liquidity crisis (e.g. due to contagion from another county), because it would provide the political validation of the debt sustainability necessary for the ECB to act (given the difficulty, in practice, of distinguishing liquidity from solvency crises). This distribution of roles between the ESM and the ECB needs to work efficiently to solve the inherent fragility of sovereign debts in the economic and monetary union (EMU) due to the prohibition of monetary financing.

However, the current instruments available at the ESM are not appropriate to solve liquidity crises, which would be highly problematic if the OMT programme ever needs to be used. That is why the ESM functions should be clearly differentiated depending on whether countries face liquidity or solvency crises. There should thus be different tracks, with at least: 1) a track for ‘pure’ liquidity crises – i.e. for countries whose economic and financial situation is fundamentally sound, but who are affected by an adverse shock beyond their control – in which the ESM would be mainly used as a political validation device for the ECB’s OMT programme; and 2) a track for clear (but exceptional) solvency crises, in which the ESM would provide funding to smooth the loss of market access, conditional on a full macroeconomic/fiscal/financial adjustment programme and on the restructuring of the sovereign debt held by private institutions.

Some elements of the agreement reached at the Eurogroup on December 4th tend to go in this direction. On one side, the modifications of the ESM’s Precautionary Conditioned Credit Line (PCCL) are aimed at increasing its accessibility during liquidity crises. On the other side, single-limb CACs would make debt restructuring smoother when a country is insolvent. Let’s take a look at these two elements in turn.

The reform of the ESM’s Precautionary Conditioned Credit Line

The main idea behind the amendment of the ESM’s PCCL is to make it more easily available for countries whose situation is sound but who are affected by shocks beyond their control. Currently, the access to the PCCL is not that easy because it is conditional on the signature of a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU). The issue – made worse by the fact that the signature of the MoU requires the unanimity of all ESM members – is that this could allow other countries to include all sorts of policy conditions to it (as argued also by Lucas Guttenberg). As a result, countries facing a self-fulfilling debt crisis, and ultimately in need of an OMT programme, might be reluctant to apply to the ESM for fear of losing economic sovereignty (and more prosaically, for governments, for fear of losing the next elections), especially countries that have recently been in a programme.

The agreement reached at the Eurogroup clarifies that the conditionality of the PCCL is with respect to ex ante criteria and not to ex post policy conditions. It would also replace the signature of an MoU by the signature of a ‘Letter of Intent’ by the country to commit to the “continuous adherence to the ex-ante eligibility criteria”. In our view, these two decisions constitute a clear improvement over the current system, as they would make the eligibility more transparent and predictable and reduce drastically the disincentive for countries to apply to an ESM programme if they need an OMT programme from the ECB. However, there are three important caveats:

The first caveat is that the agreed ex-ante eligibility criteria are particularly tight.

What are these five criteria exactly? First, to access the revamped PCCL, countries will have to meet the three following quantitative benchmarks in the two years preceding the request for support:

- the debt benchmark, which requires member states to have a debt-to-GDP ratio below 60% or a reduction in this ratio of 1/20th per year

- the minimum benchmark, which is the level of the structural balance providing a safety margin against the 3% threshold under normal cyclical conditions (and which is used as one of three inputs into the calculation of the minimum MTO)

- the deficit rule, which means that the deficit has to be below 3% of GDP

Second, they would also need to comply with two qualitative conditions related to EU surveillance:

- not experiencing Excessive Imbalances

- not being subject to the Excessive Deficit Procedure

In addition to these five criteria, debt should be considered sustainable.

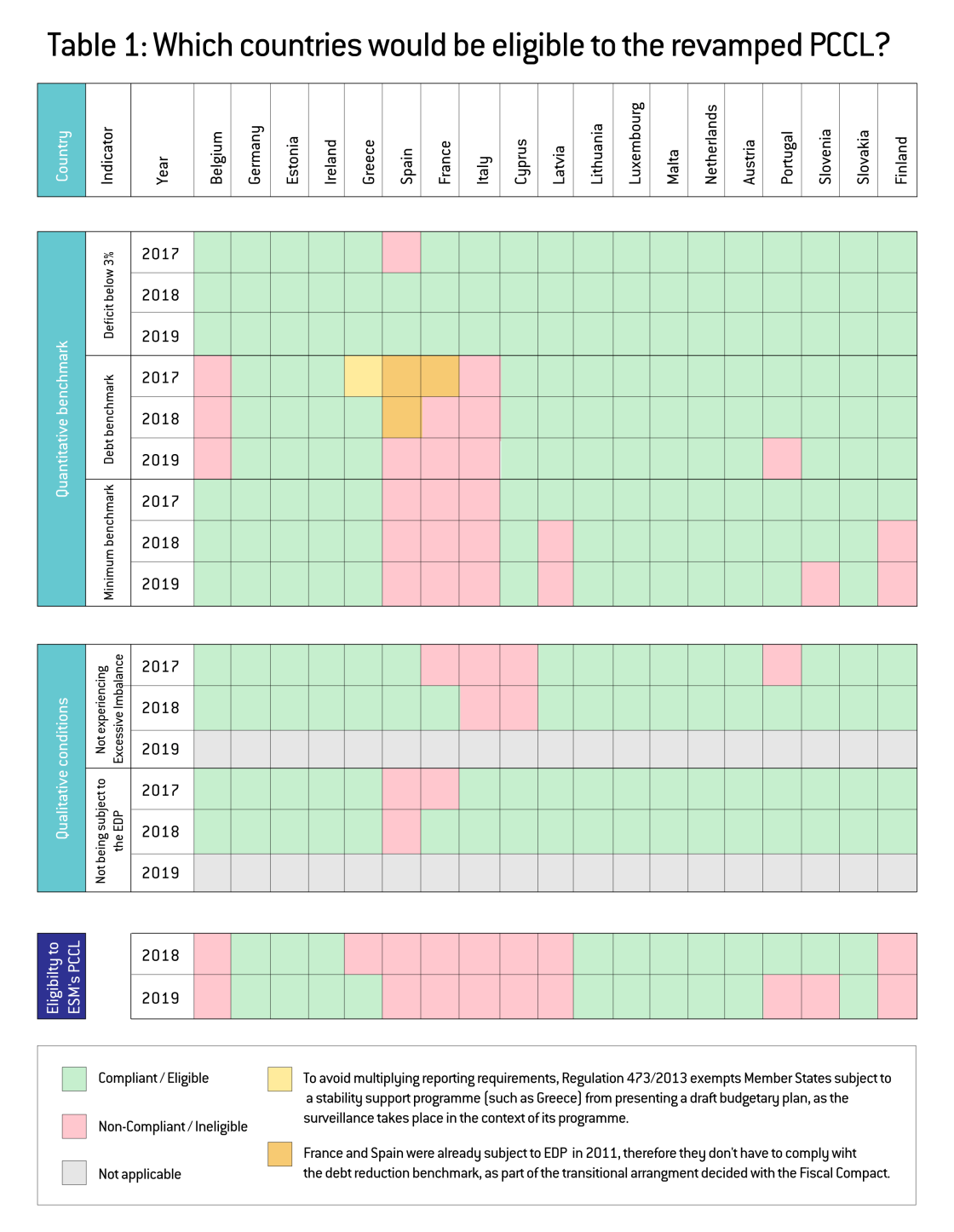

To see how stringent these criteria are, we have applied these criteria to all euro-area countries to see which ones would currently be eligible to the PCCL. Our results are reported in Table 1: ultimately, among the 19 countries of the EMU, according to the criteria laid out in the Eurogroup agreement, 10 countries (representing 56% of the Eurozone’s GDP) would not be able to access it at the moment if they needed to: Cyprus, Finland, France, Italy, Latvia and Spain as well as (depending when exactly the request would be made) Greece, Portugal and Slovenia.

Sources: Ameco, European Commission’s opinions on draft budgetary plan (2017 and 2018), Macroeconomic Imbalance Procedure (2018). Notes: full details are available in the excel file attached.

It is actually interesting to compare the eligibility criteria agreed in the Eurogroup with the current criteria:

- Compliance with the fiscal rules, even if a country is subject to an Excessive Deficit Procedure, as long as the country follows the Council’s decisions and recommendations

- A sustainable government debt

- Compliance with the requirements of the Macroeconomic Imbalances Procedure, even if a country is subject to an Excessive Imbalances Procedure

- A track record of access to capital markets on reasonable terms

- A sustainable external position

- No systemically relevant bank solvency problems

Most of the criteria overlap, but some of the new ones are actually much more constraining, in particular the ones concerning the fiscal rules. They are more precise, which is a good thing, but might also be more difficult to meet. The risk would thus be that countries that need this instrument at some point might not be able to use it.

The second caveat is that one of the eligibility criteria is based on the structural deficit.

As argued in depth in a paper written with Zsolt Darvas and Álvaro Leandro, the structural deficit is not observable and its estimation suffers from major flaws that lead to severe mismeasurement errors, particularly in real time. It is therefore inadequate to use it as an eligibility criterion to access a revamped PCCL, as it could lead to serious mistakes or, at the very least, to endless discussions and negotiations between member states, the Commission and the ESM (e.g. a couple of years ago, finance ministers of eight euro-area countries expressed serious doubts about the use of these estimations in the EU fiscal framework).

As a result, this would reduce the transparency, predictability and more importantly the objectivity of the eligibility process, which are the main purposes of the reform. Any reference to cyclically adjusted variables should thus be dropped from the eligibility criteria. Moreover, it is noteworthy that the expenditure benchmark, despite being the basis of the fourth rule of the EU fiscal framework, does not appear in the eligibility criteria (despite a strong consensus building up in recent years around the fact that an expenditure rule could be superior to other rules, see for instance here, here or here).

The third – and most important – caveat is that it is not totally clear if being eligible to an ESM’s PCCL would be sufficient to be considered eligible to the ECB’s OMT programme.

Indeed, the ECB’s OMT press release is rather ambiguous on that matter. The ECB’s guidelines state that the OMT is conditional on an ESM programme and that “such programmes can take the form of a full EFSF/ESM macroeconomic adjustment programme or a precautionary programme (Enhanced Conditions Credit Line), provided that they include the possibility of EFSF/ESM primary market purchases”. The ECB thus mentions explicitly precautionary programmes (which include PCCL) and primary market purchases (which are possible under PCCL) but it also singles out the Enhanced Conditions Credit Line between parentheses. It is difficult to know if it is meant to be an example of a precautionary programme or to exclude the PCCL. We are not aware of any other document of the ECB or any speech by the members of the Governing Council that clarifies this essential question.

We think that, given the strong ex-ante eligibility criteria and the approval of the ESM’s Board (composed of the finance ministers of the euro area), the access to a PCCL should be considered enough for the ECB as a political validation to be able to launch an OMT programme in case of a liquidity crisis (if the ECB thinks it is necessary within its mandate). Therefore, before the reform of the ESM is formally approved, the ECB should clarify its original OMT press release and state that a PCCL should be considered sufficient as a pre-condition to activate an OMT programme.

The inclusion of single limb CACs

Concerning the introduction of single-limb CACs in sovereign bonds by 2022, we do not think that this would fundamentally change the characteristics of euro-area sovereign bonds but we see it as a positive development. In fact, the ESM treaty already mandated the inclusion of two-limb Euro CACs in all new euro-area government securities, with maturity above one year, issued after 1 January 2013. The difference between the two types of CACs is that the single-limb CAC allows a restructuring of the debt across all bonds’ series with a single supermajority requirement, while in the two-limb version a restructuring of the debt across all bonds’ series requires two supermajority votes – one at the aggregate level and one for each bond issuance.

The two-limb Euro CACs thus fall short of eliminating holdouts (which can be quite costly and an obstacle to a smooth debt restructuring as the Greek case showed). However, as explained by Martinelli (2016), when the ESM treaty was signed, two-limb CACs were preferred to single-limb ones, because of the fear that small creditors could be treated unfairly in debt restructurings with single-limb CACs. But, since then, a solution has been found to this issue by adding to the single-limb CAC the condition that all creditors be treated equally.

That is why we think that the replacement of two-limb CACs by one-limb ones would be a small but positive improvement to the system. It does not per se increase the probability of a debt restructuring but, in the exceptional case in which this would take place, it would smooth the process and reduce the cost for the sovereign, as it would not have to deal with holdouts. In parallel to building a proper ESM ‘liquidity track’ that allows euro-area countries to access to the OMT, this measure would participate in the building of a proper ‘solvency track’ for countries that are clearly insolvent and would benefit from a clean debt restructuring.

Conclusions

Overall, despite the fact that the Eurogroup agreement reached on December 4th did not provide the solution to all the missing pieces of the euro architecture in order to make it more resilient (such as a stabilisation function, the full completion of the banking union thanks to the establishment of EDIS, or the improvement of the fiscal rules), the agreement nevertheless made some progress on some technical details.

The deal reached contains a number of improvements: first, making clear that the ESM’s PCCL is conditional on transparent and precise ex-ante eligibility criteria and not on ex-post policy conditions, while replacing the PCCL’s MoU by a ‘Letter of Intent’ should help reduce the strong disincentives to use the ESM, and thus to access to the OMT, in the case of liquidity crises. Second, replacing two-limb CACs by single limb CACs, although not a game changer per se, might facilitate debt restructuring in exceptional insolvency crises.

However, the reform of the ESM toolkit that has been agreed by the finance ministers of the euro area could still be improved at the Euro Summit, where the heads of states and governments will gather at the end of the week. First, the conditions to access the PCCL are particularly tight, which could in the end make the instrument totally useless (more than half of the countries would not be able to use it today). Second, one of the eligibility criteria is based on structural deficit, which is an impractical indicator plagued with measurement issues. Using it as an eligibility criterion is inadequate and this criterion should be dropped. Finally, all of this might be useless if the ECB does not recognise the PCCL has a suitable programme to access the OMT. It is therefore important that the ECB clarifies its position on the access to OMT before the final decision is signed off.